I recently presented a brief and rough comparison of philosophers Wilfrid Sellars and Edmund Husserl on the subject of science, its place in the world, and the social crises of modernity. Specifically, I drew a few lines between Husserl’s concept of the “life-world” in The Crisis of the European Sciences (1938, excerpts available at link) and Sellars’ idea of the “manifest image,” as described in Philosophy and the Scientific Image of Man (1962, complete text at link). Both tackle one of the central problems of the modern age: how to square scientific knowledge with the “unscientific” parts of the world, be they social, ethical, mental, or metaphysical.

While the post-war American Sellars and the intrawar German Husserl use vastly different vocabularies and start from vastly different perspectives, there are some notable points of agreement. Their hopes for a nonreductive unification of science and society hold great appeal. It is an abstracted and generalized picture of my personal experiences with truth and muddlement.

I only quote Sellars below, because I found I got whiplash from alternating between Sellars’ and Husserl’s equally tortuous but wholly opposing styles. To orient, some excerpts from Husserl’s Vienna lecture:

I, too, am quite sure that the European crisis has its roots in a mistaken rationalism. That, however, must not be interpreted as meaning that rationality as such is an evil or that in the totality of human existence it is of minor importance. The rationality of which alone we are speaking is rationality in that noble and genuine sense, the original Greek sense, that became an ideal in the classical period of Greek philosophy – though of course it still needed considerable clarification through self-examination. It is its vocation, however, to serve as a guide to mature development.

The philosophy that at any particular time is historically actual is the more or less successful attempt to realize the guiding idea of the infinity, and thereby the totality, of truths. Practical ideals, viewed as external poles from the line of which one cannot stray during the whole of life without regret, without being untrue to oneself and thus unhappy, are in this view by no means yet clear and determined; they are anticipated in an equivocal generality. Determination comes only with concrete pursuit and with at least relatively successful action. Here the constant danger is that of falling into one-sidedness and premature satisfaction, which are punished in subsequent contradictions. Thence the contrast between the grand claims of philosophical systems, that are all the while incompatible with each other. Added to this are the necessity and yet the danger of specialization.

In this way, of course, one-sided rationality can become an evil. It can also be said that it belongs to the very essence of reason that philosophers can at first understand and accomplish their infinite task only on the basis of an absolutely necessary onesidedness. In itself there is no absurdity here, no error. Rather, as has been remarked, the direct and necessary path for reason allows it initially to grasp only one aspect of the task, at first without recognizing that a thorough knowledge of the entire infinite task, the totality of being, involves still other aspects. When inadequacy reveals itself in obscurities and contradiction, then this becomes a motive to engage in a universal reflection. Thus the philosopher must always have as his purpose to master the true and full sense of philosophy, the totality of its infinite horizons. No one line of knowledge, no individual truth must be absolutized. Only in such a supreme consciousness of self, which itself becomes a branch of the infinite task, can philosophy fulfill its function of putting itself, and therewith a genuine humanity, on the right track. To know that this is the case, however, also involves once more entering the field of knowledge proper to philosophy on the highest level of reflection upon itself. Only on the basis of this constant reflectiveness is a philosophy a universal knowledge.

The reason for the downfall of a rational culture does not lie in the essence of rationalism itself but only in its exteriorization, its absorption in ‘naturalism’ and ‘objectivism’.

Edmund Husserl, The Vienna Lecture (tr. David Carr)

Willem deVries’ essay on Sellars at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is a superb overview of Sellars’ philosophy. Here are a few of his remarks on Sellars’ concepts of the manifest image and the scientific image:

The manifest image is neither frozen nor unchanging. It can be refined both empirically and categorically…Thus, the manifest image is neither unscientific nor anti-scientific. It is, however, methodologically more promiscuous and often less rigorous than institutionalized science. Traditional philosophy, philosophia perennis, endorses the manifest image as real and attempts to understand its structure.

One kind of categorial change, however, is excluded from the manifest image by stipulation: the addition to the framework of new concepts of basic objects by means of theoretical postulation. This is the move Sellars stipulates to be definitive of the scientific image. Science, by postulating new kinds of basic entities (e.g., subatomic particles, fields, collapsing packets of probability waves), slowly constructs a new framework on this basis that claims to be a complete description and explanation of the world and its processes. The scientific image grows out of and is methodologically posterior to the manifest image, which provides the initial framework in which science is nurtured, but Sellars claims that “the scientific image presents itself as a rival image. From its point of view the manifest image on which it rests is an ‘inadequate’ but pragmatically useful likeness of a reality which first finds its adequate (in principle) likeness in the scientific image” (PSIM, in SPR: 20; in ISR: 388).

Is it possible to reconcile these two images?…The manifest image is, in his view, a phenomenal realm à la Kant, but science, at its Peircean ideal conclusion, reveals things as they are in themselves. However, despite what Sellars calls “the primacy of the scientific image”(PSIM, in SPR: 32, he ultimately argues for a “synoptic vision” in which the descriptive and explanatory resources of the scientific image are united with the “language of community and individual intentions,” which “provide[s] the ambience of principles and standards (above all, those which make meaningful discourse and rationality itself possible) within which we live our own individual lives” (PSIM, in SPR: 40).

Willem deVries, Wilfrid Sellars (in SEP)

And two further remarks (with which not all Sellarsians would agree) on Sellars’ conception of science in a normative social realm:

Science, for Sellars, does not aim to construct an adequate representation of the world given a fixed stock of basic concepts or terms; it aims to change our concepts and terms to enable us to anticipate, explain and plan ever better our interaction with reality. Science is the methodologically rigorous attempt to reform and extend the descriptive resources of language to better equip us in all those tasks that presuppose descriptive language. (148)

Science envisages abandoning the manifest image and its norm-laden objects, but it cannot in fact do so without undercutting itself. The manifest image is transcendentally ideal but empirically and practically real. The world in which we live and have our being is necessarily a world of sensible objects that we constantly evaluate with regard to their aiding or impeding our intentions. We are simply built that way. This manifest world is grounded in, but not identical to, the world science reveals to us. (161)

Willem deVries, Wilfrid Sellars (Acumen)

So thus, on the vision and immense challenges of a truly universal, non-parochial science carried out in a rational and tolerant society–the “infinite task.”

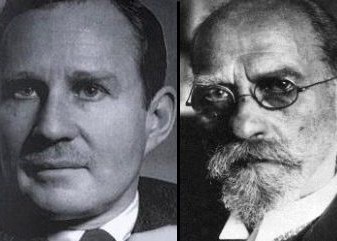

Edmund Husserl and Wilfrid Sellars

(All quotes below are from Philosophy and the Scientific Image of Man unless otherwise stated.)

Marvin Farber led me through my first careful reading of the Critique of Pure Reason and introduced me to Husserl. His combination of utter respect for the structure of Husserl’s thought with the equally firm conviction that this structure could be given a naturalistic interpretation was undoubtedly a key influence on my own subsequent philosophical strategy.

WS, Autobiographical ReflectionsOne seems forced to choose between the picture of an elephant which rests on a tortoise (What supports the tortoise?) and the picture of a great Hegelian serpent of knowledge with its tail in its mouth (Where does it begin?). Neither will do. For empirical knowledge, like its sophisticated extension, science, is rational, not because it has a foundation but because it is a self-correcting enterprise which can put any claim in jeopardy, though not all at once.

WS, Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind §38

Sellars and Husserl are both trying to provide a holistic structure for the mind’s universalizing scientific engagement with the world. The difference lies in their methods: where Husserl is transcendental-historical and phenomenological, Sellars is pragmatist and naturalistic. The Lifeworld and the Manifest Image share the same methodological primacy in determining how we look at the world. They are “given” or “pre-given”: we have come to them without being aware of the processes by which they arose—or if we ever were aware of them, we have forgotten them. But for Sellars, the idea of the “image” or model is crucial: the Manifest and Scientific Image both are inexact pictures of reality which undergo repeated refinement.

Let me refer to these two perspectives, respectively, as the manifest and the scientific images of man-in-the-world…By calling them images I do not mean to deny to either or both of them the status of ‘reality’. I am, to use Husserl’s term, ‘bracketing’ them, transforming them from ways of experiencing the world into objects of philosophical reflection and evaluation…While the main outlines of what I shall call the manifest image took shape in the mists of pre-history, the scientific image, promissory notes apart, has taken shape before our very eyes.

The Manifest and Scientific Images both are idealized concepts established communally. Truth and falsity exist in each of them through communal norms of rationality and discourse. While images may be refined or discarded, normative standards of correctness nonetheless exist with regard to any image.

Pragmatism: The point I wish to make now is that since this image has a being which transcends the individual thinker, there is truth and error with respect to it, even though the image itself might have to be rejected, in the last analysis, as false.

From “I” to “We”: Yet the essentially social character of conceptual thinking comes clearly to mind when we recognize that there is no thinking apart from common standards of correctness and relevance, which relate what I do think to what anyone ought to think. The contrast between ‘I’ and ‘anyone’ is essential to rational thought.

Their own methodologies, however, are opposite. Husserl tends toward transcendental idealism; Sellars towards a nominalistic physicalism. For Husserl, the ego is transcendental; for Sellars, it is a theoretical construct that, in its “givenness,” we have come to take for granted. For Sellars, the “given” (in at least one of its forms) is that knowledge which we gain exclusively through pure, raw experience or being-in-the-world. Sellars is very clear: no such knowledge exists. Any such seeming knowledge is acquired against the holistic background of a theoretical structure, even if we are not conscious of that structure. Scientific investigation can reveal that structure. The Manifest Image cannot, because it is unable to get around its own theoretical presuppositions and reliance on subjectivity:

A Point of Difference: The manifest image must, therefore, be construed as containing a conception of itself as a group phenomenon, the group mediating between the individual and the intelligible order. But any attempt to explain this mediation within the framework of the manifest image was bound to fail, for the manifest image contains the resources for such an attempt only in the sense that it provides the foundation on which scientific theory can build an explanatory framework; and while conceptual structures of this framework are built on the manifest image, they are not definable within it. Thus, the Hegelian, like the Platonist of whom he is the heir, was limited to the attempt to understand the relation between intelligible order and individual minds in analogical terms.

I see this possibly as the fundamental difference between Husserl and Sellars: for Sellars, phenomenological investigation alone cannot get around the theoretical structure necessary for it. Any transcendental phenomenology remains a contingent construct. For Sellars, bracketing (the epoche) should include subjectivity and experience itself—they cannot explain themselves.

Nonetheless, for both of them, science is unique in its potential universality, the Manifest Image being too tied to cultural norms and historical caprice and false first principles to withstand substantive debate over its contents, unlike the “self-correcting enterprise” of science.

Science as a Rival Image: Yet, when we turn our attention to ‘the’ scientific image which emerges from the several images proper to the several sciences, we note that although the image is methodologically dependent on the world of sophisticated common sense, and in this sense does not stand on its own feet, yet it purports to be a complete image, i.e. to define a framework which could be the whole truth about that which belongs to the image. Thus although methodologically a development within the manifest image, the scientific image presents itself as a rival image. From its point of view the manifest image on which it rests is an ‘inadequate’ but pragmatically useful likeness of a reality which first finds its adequate (in principle) likeness in the scientific image. I say, ‘in principle’, because the scientific image is still in the process of coming into being.

Yet for both Sellars and Husserl, science has also fallen prey to a certain kind of “givenness,” though their attacks differ. Husserl critiques the sciences as having forgotten the historical circumstances in which they arose, having become “sedimentized” with naturalistic assumptions. Sellars, on the other hand, critiques the sciences’ foundationalism. That is, Sellars also accuses science of having established a false, ahistorical, positivist and empiricist ground on which they build a world image distinct from that of the Manifest Image or Husserl’s Lifeworld. For Sellars it is not so much that science’s foundation has become “sedimentized” as much as that the foundation never existed to begin with. History helps to expose the cracks in the foundation by exploring how it was that this foundation was established, but it is not the case that we have obscured a previous way of being, only that we are taking aspects of our current way of thinking for granted. We have misunderstood the nature of what science is. It does not and cannot provide a new foundation that wipes out the manifest image in one blow.

Holism : For each scientific theory is, from the standpoint of methodology, a structure which is built at a different ‘place’ and by different procedures within the intersubjectively accessible world of perceptible things. Thus ‘the’ scientific image is a construct from a number of images, each of which is supported by the manifest world.

While Sellars replace positivism with a broader, more holistic, pragmatic, and fallibilist methodology, he also attempts to expose the “givenness” of the Manifest Image. In the Manifest Image, people participate in discourse that establishes a linguistic idealism through the existence of shared concepts expressed through language. These concepts are internalized by us, often becoming second nature.

Our first-person thoughts are his prime example of an implicit theoretical construct. Elsewhere, in Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind, Sellars attempts to show that the very existence of “thoughts” depends on a rational discursive linguistic community, what Sellars terms the “space of reasons.” What we take to be “given” in our minds actually depends on a learned communal conceptual structure. And this anti-foundationalism attacks both the givenness of the Manifest Image itself and the positivistic empirical basis of science. In both cases, there is an implicit, complex, historically-established theoretical structure that undergirds even the simplest of thoughts and perceptions.

This attack does not invalidate the Manifest Image, as we still inhabit it and the concepts of personhood and the discursive community are essential to establishing the norms by which we live. But because the Manifest Image is incomplete and insufficient—our “given” ideas not able to form a coherent explanation of reality—the Scientific Image appears as a potentially more satisfactory picture of reality to understanding ourselves and the world—as long as we do not see it as wholly substitutive. We should not be looking to evolutionary psychology to explain the nature of morality.

My primary concern in this essay is with the question, ‘in what sense, and to what extent, does the manifest image of man-in-the-world survive the attempt to unite this image in one field of intellectual vision with man as conceived in terms of the postulated objects of scientific theory?’ The bite to this question lies, we have seen, in the fact that man is that being which conceives of itself in terms of the manifest image. To the extent that the manifest does not survive in the synoptic view, to that extent man himself would not survive.

As with Husserl, we will find ourselves in crisis if we take our contemporary Scientific Image to be real rather than an approximate image or model. The Scientific Image should ideally converge on the real in a way that the Manifest Image has failed to, but it does not and cannot stand independently of the Manifest Image in which we exist. Hence Sellars’ emphasis on the need for a Synoptic Image in which the discursive normativity of the Manifest Image and the fallibilist, revisionary Scientific Image allow us to achieve a satisfactory methodology of philosophical-scientific investigation.

The Merging of the Images: Thus the conceptual framework of persons is the framework in which we think of one another as sharing the community intentions which provide the ambience of principles and standards (above all, those which make meaningful discourse and rationality itself possible) within which we live our own individual lives. A person can almost be defined as a being that has intentions. Thus the conceptual framework of persons is not something that needs to be reconciled with the scientific image, but rather something to be joined to it. Thus, to complete the scientific image we need to enrich it not with more ways of saying what is the case, but with the language of community and individual intentions, so that by construing the actions we intend to do and the circumstances in which we intend to do them in scientific terms, we directly relate the world as conceived by scientific theory to our purposes, and make it our world and no longer an alien appendage to the world in which we do our living.

Appendix: Husserl’s Response

I am closer to Sellars’ stance than Husserl, lacking his transcendental sympathies. But Richard M. Bernstein gave an account of what he thought Husserl’s response to Sellars could be, which I excerpt here:

It is clear even from Husserl’s preliminary characterizations of the Lebenswelt, and what he takes to be its general structures, that he would criticize Sellars’ own account of the manifest image — especially in regard to what Sellars calls empirical and categorial refinement — as being infected by categories rooted in objective science. He would accuse Sellars of not being “philosophically radical” enough in bracketing the manifest image and providing an analysis of its structure.

But how are we to perform such an investigation? What is the ground for such a “new” science? Here we touch upon the most fundamental theme in Husserl, one which he took to be a radical turn — though he also claims it has been the telos of philosophical reflection itself: the transcendental epoché that makes possible a transcendental reduction. When we bracket the ontological claims of the Lebenswelt and perform the epoché, “we are not left with a meaningless, habitual abstention, rather, it is through this abstention that the gaze of the philosopher in truth first becomes fully free: above all, free of the strongest and most universal, and at the same time most hidden, internal bond, namely, of the pregivenness of the world” (p. 151 ). When we have freed ourselves by means of this transcendental epoché, is it possible to recognize the Lebenswelt and mankind itself as “a self-objectification of transcendental subjectivity.”

The transcendental epoché — the philosophical act of pure reflection -which involves a personal and intellectual transformation of the philosopher, is not to be understood as a “turning away” from “natural human life-interests.”

According to Sellars, once we clarify the differences and relationships between the types of scientific activity appropriate to the manifest image and to the scientific image proper, then we grasp the essential unity of science. This unity not only reconciles the two types of scientific endeavor appropriate to the two images, but also indicates the essential unity between the natural and the social sciences. Extrapolating what Sellars says about behavioristics, we can extend his principle to the distinctively social sciences such as economics, political science, and sociology, and claim that these disciplines also involve the techniques of correlational induction appropriate to the manifest image.

But it is precisely here that we find the deepest and the most consequential clash between Sellars and Husserl. Husserl too takes psychology itself as a “decisive field” (p. 203 ). And his judgment about the science of psychology — both behavioristic and nonbehavioristic — is that it has been a failure. And while Husserl also focuses on psychology, it is clear that he is pressing an indictment against all forms of naturalism and objectivism in the sciences of human life. In the attempt to apply the methods of the natural sciences to an understanding of human subjectivity and intersubjectivity, these disciplines have not only failed, but distorted the phenomena studied. This failure is not one that can be overcome by more sophisticated development of the methods and techniques of the natural sciences. “It has already become clear to us that an ‘exact’ psychology, as an analogue to physics…is an absurdity. Accordingly, there can no longer be a descriptive psychology which is the analogue of a descriptive natural science. In no way, not even in the scheme of description vs. explanation, can a science of souls be modeled on natural science or seek methodical counsel from it. It can only model itself on its own subject matter, as soon as it has achieved clarity on this subject matter’s own essence” (p. 223). If it is objected that a “genuine” psychology is not a “science of souls,” but a science of observable behavior, this does not weaken Husserl’s charge, for psychology conceived in this manner will never be able to illuminate the structures of human subjectivity and intersubjectivity.

Richard M. Bernstein, The Restructuring of Social and Political Theory

My gut reaction is that Sellars and Husserl are most at odds over the very distant “end of inquiry,” which is such a distant and hypothesized and never-to-be-reached point that arguments over it are not just irresolvable, but close to meaningless. I think that Sellars’ “synoptic view” could ultimately allow for scientific accounts of what Husserl wants (who’s to say it couldn’t?), while Husserl seems like he might be amenable to an expanded definition of naturalism and objectivism–his problem is with those terms in their current form. So I’m not sure the disagreement Bernstein lays out would necessarily amount to more than a terminological dispute however many thousands of years into the future it would take before science nearly gets reality right.

Husserl and Sellars’ prescriptions for science today, however, still seem rather close. Both admit the broad failings of scientific theory and method, and both want to use the fundamental methodological conceptions of science to reform it. They both ask us all to own up to the failures and idiocies and prejudices that mar scientific practice, and try not to be so arrogant and half-assed in the future.