In The Stupidity of Computers, I discussed how computers require rigidly defined ontologies, which are then enforced on us. What happens in the collision between slippery life and a fixed ontology? Here is a case study. Here the fixed ontology is that of video games, and the “life” is the Christian religion.

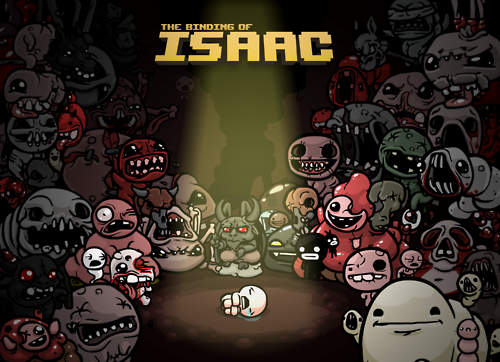

The Binding of Isaac is an indie game by Edmund McMillen (art and design) and Florian Himsl (programming) about a boy, Isaac, with an insane fundamentalist Christian mother. When she hears the voice of God telling her to kill Isaac (as seen in the opening cutscene), Isaac flees into the basement and fights the terrible creatures therein, going deeper and deeper into the basement until confronting Mom herself (and, later in the game, Satan). You, as Isaac, shoot tears at the enemies to kill them. The enemies, which include all manner of biological horrors (fistulae, fetuses, pinworms, blastocysts, and lots of bugs), all try to kill you.

Bosses include Mom, Satan, Pin, Chub, Fistula, Blastocyst, the Blighted Ovum, Scolex, Loki, the Seven Deadly Sins, and the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (image c/o Binding of Isaac Wiki)

The game itself is firmly neo-classicist. It is a top-down 2D action game that will look familiar to people who played Legend of Zelda. The basic mechanics are the same: you control a character moving from room to room in a maze and killing enemies. There are multiple levels, with difficult bosses at the end of each level. You pick up power-up items that increase your character’s skills in one way or another: speed, damage, health, etc. (Some items hurt you, some are a mixed bag.)

The game is extraordinarily difficult, requiring way more coordination and reflexes than I possess, and it is unforgiving: death sets you back to the beginning every time. But for the dextrous it is prodigious, and because of the randomly generated levels and a plethora of unlockable items, secrets, and endings, the game has picked up a well-deserved diehard following. While traditional, the game is far more elaborate and skillful than the norm–McMillen clearly has spent a great deal of time thinking about gameplay construction and balance. (McMillen did the similarly neo-classical Super Meat Boy, a punishing platformer requiring utterly precise split-second timing.)

But the story and the symbols are what concern me, and specifically the mapping of the game’s symbols to the game’s functional roles.

Courtesy of the Binding of Isaac Wiki, which has an exhaustive list of items, enemies, and everything else in the game, consider a few game items (that is to say, symbols) and their functional roles in the game :

These power-up items have perfectly traditional functions, making Isaac faster, giving him more health points, or increasing his tear firepower. What’s left for the player to infer is why the items have the functional effects they do. This knowledge is irrelevant to the game’s function but contributes to the underlying “story.” So the Wooden Spoon, as well as another item, the Belt, increase speed because Isaac was beaten and he runs from them. Stem cells are both anti-Christian and associated with health. The Wire Coat Hanger, a reminder of abortion, would make a good Christian boy cry.

(Sometime the notable inferences are not between symbol and functional role but between name and image. Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner, and Dessert all increase health, but the item images are of dog food and spoiled milk.)

But some links are left vague or underdetermined. Why does the Wire Coat Hanger go through Isaac’s head after you pick it up? Maybe just for gross-out purposes, or maybe because Isaac’s mother wanted to abort him? Very little exposition is explicitly given in the brief story cut-scenes, leaving ambiguous the extent to which all these horrible things actually happened to Isaac.

Also, the symbolism does not seem to be especially organized: Judeo-Christianity is the dominant note, but bits and pieces appear from other mythologies such as an ankh, a tarot deck, Polyphemus, the Necronomicon, and many references to other games. In addition to Isaac, you can play as Judas, Cain, Eve, Magdalene, or Samson. (References to Jesus in the game, however, are exceedingly rare.) These characters are ultimately just Isaac’s alter ego, with Eve and Magdalene contributing to a strong implication that Isaac likes to cross-dress.

So the mappings from symbol to functional role are fairly piecemeal, constructed with an eye toward gameplay rather than a perfectly coherent story per se. For example, Isaac is able to use “holy” and “Satanic” items alike and in combination with little incident:

| Item | Effect | Info |

|---|---|---|

| The Bible | Transforms the player into an angel, allowing him or her to fly over obstacles for the current room only. | Instantly kills Mom, Mom’s Heart, and It Lives. Satan or Isaac will instantly kill you for using it, even after death (unless you have The Wafer). |

| The Book Of Belial | Doubles damage until you exit the room, just like The Devil tarot card. It also gives Isaac an angry face with empty eye sockets with blood running down his face until he exits the room. | Unlocked by beating the full game. Can rarely be found in secret rooms and the devil room. Judas starts the game with this item. |

| Rosary | Increases Faith by adding 3 Soul Hearts and increases the chance for a Bible to appear in the subsequent levels of the playthrough. Found in Item Room and Shop. |  Isaac has a cross amulet. |

| The Pact | Increases Damage by 1 and rate of fire by 2. The player also gains 2 soul hearts. If you have Transcendence when you pick up The Pact, you will have a body again, but with demon wings like the Lord of the Pit item grants. Available by defeating ‘The Fallen‘ or traded in a Devil Room. |  Turns the player’s body black, gives him small horns, and makes him seem more aggressive. |

While using the Bible on Satan (or the final final boss, who is Isaac him/yourself) will kill you, this is more the exception than the rule. I’m not sure to what extent it was intended that possessing the Wafer prevents you from dying if you use the Bible to fight Satan, or even what the symbolic import of it is. There are so many items that the interactions between them (such as Transcendence and The Pact, another baffling combination) were probably determined ad hoc, especially as many items were added in several updates after the game’s initial release.

I don’t mean to say that the symbolism is a meaningless mishmash. The story and content are deeply significant to McMillen: in an interview he discussed his oppressive born-again upbringing, as well as the disappointment he felt upon realizing that the entire world of the Bible was not real. The links between games and religion are very real to him: “I think Catholicism is quite interesting. It’s very close to D&D.”

But I’m not sure that aside from memorably grotesque dark humor, the specific symbol set has contributed that much to the game’s popularity. When you are dodging 15 enemies while shooting explosive projectiles at them, it doesn’t matter whether the enemies are spaceships or aborted fetuses, or whether the projectiles are missiles or your own vomit/tears/urine.

| Item | Effect | Info |

|---|---|---|

| Number One | Sets the player’s tears to their maximum rate of fire and minimum range. Combining Number One with Technology causes the fire rate to increase significantly and turns the beam yellow. Bug: Collecting The Mark (and maybe other tear-changing items) before collecting Number One increases your rate of fire to max, but doesn’t decrease your range. |  Isaac stops crying and smiles while yellow colored projectiles (urine) come from his lower body rather than his face. |

| Ipecac | Green projectiles fired from the mouth causing poison/explosive damage. Shots are fired in an arc, so they will fly over enemies unless extremely close (close enough to take damage from the explosion). |  Isaac gets very sick and he spits his projectiles. |

The symbolism is not irrelevant to the gameplay, however. Seemingly incidental details make a difference to how various pieces of the game interact functionally. For example: Cain only has one eye, so if you play as Cain and he picks up the weapon Technology (an eye laser), he can no longer shoot tears out of his other eye. The other characters still can. Here the symbol dictated part of the functional role.

But the symbolism only inconsistently has such functional impact. One can make deals with the Devil himself (before fighting him later in the game), and while you won’t be able to purchase holy items from him, items like Guppy’s Head and A Quarter lack a certain Satanic elan possessed by other Deal with the Devil items like the Pact, Lord of the Pit, and Whore of Babylon.

| Item | Effect | Info |

|---|---|---|

| Guppy’s Head | Spawns 2-4 Blue Flies to damage enemies. Flies won’t spawn if entering a door while using it. | Found in Devil Room for 2 hearts, Red Chests, Challenge Room or as a drop from fight with The Fallen. If you collect any three of the Guppy’s items (Guppy’s Head, Guppy’s Tail, Guppy’s Paw, Dead Cat), Isaac will becomes Guppy. If it’s Guppy’s Paw or Guppy’s Head, you only need to use it once (you can drop it afterward) to make the game counts you as “carrying” the item. |

| Whore of Babylon | If you have half a heart, a message reading “What a horrible night to have a curse…” appears on the screen and the player becomes the Whore of Babylon. This increases their damage by 3 and speed by 2 and they will stay in that form until leaving a room with more than half a heart.Eve starts the game with this item. Found in the Devil Room, Item Room or after defeating The Fallen. Might appear in the shop for 2 hearts or 15 coins as well. When activated while the player has Fate, the Holy Grail, or the Bible activated, the wings turn black. |  Isaac becomes a spawn of Satan. |

| The Mark | Increases Damage by 2 and adds one soul heart. Will kill you if you have 2 or less hearts when you make the devil deal despite giving you one soul heart. Available by defeating The Fallen or traded in a Devil Room. |  Isaac sports three 6’s in a circular pattern. |

We are very close, then, to a world of allegory, except that in relation to Christian allegory, the terms have been reversed. Instead of mapping a world of secular symbols onto a common and uniform religious conceptual scheme, religious symbols are mapped, somewhat haphazardly, onto the firmly fixed conceptual vocabulary of a video game.

Allegory is only possible (and popular) within a community in which there is a shared conceptual vocabulary to allegorize. Religion is ideal for this purpose, providing such an overarching unity of conceptual arrangement that most members of that religious community stand a good chance of decoding the allegory. Mapping the plot and symbols of William Langland’s medieval allegory Piers Plowman onto Christian concepts may not be blatantly obvious, but it is a process firmly enmeshed in the dominant religious conceptual arrangement of the period.

In the absence of a complex religious vocabulary, certain cultural universals like beauty, sex, and death are also manageable for allegorical purposes, but anything more specific, such as politics, poses a problem. If the reader does not feel the allegorical basis of the story, the allegory may just appear empty and contrived, or even incomprehensible.

In a restricted conceptual vocabulary, such as that of a top down 2D game, the problem of a lack of shared vocabulary disappears. Every player knows the conceptual vocabulary of health, shots, power ups, enemies, and bosses. Their significance within the game is indisputable: they amount to how you play and win the game. They form the ontology of a video game.

As for decoding the allegory, the symbolic mapping is made explicit, even if the meaning of the mapping is not. The Belt and the Wooden Spoon increase Isaac’s speed, but one must then infer that they do so because Isaac has been beaten with them. Having the Whore of Babylon item gives you far more firepower, but only if you’re very low on health. And so players begin to use a Judeo-Christian symbology in a very particular and peculiar way because The Binding of Isaac makes use of them in a rigidly allegorical context.

McMillen clearly feels this allegory quite deeply. But what about players, to whom these symbols may have much less powerful associations? The game must have an influence, however small, on how players will think of those symbols. The computer doesn’t care whether the damaging projectiles are bullets, tears, or urine, but because these terms are used in other contexts, their binding to the conceptual realm of the video game has some impact.

This impact was not calculated, nor is it easily grasped. The symbology is based on the Judeo-Christian mythos while not being beholden to it. The Binding of Isaac is striking because it is such an extreme case and uses a symbology that has rarely (if ever) been put to such use in a video game before. But in participating in a mapping from symbols to an ontology, we participate in the mutation of the meaning of those symbols. The individual functional roles of video games bleed into the symbols they use and stay with us every time we see a wafer, a fistula, or a Bible thereafter.

![themarriage[1]](http://www.waggish.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/themarriage1.gif)