The great anthropologist Inga Clendinnen recently passed away. I had greatly enjoyed her speculative yet rigorous The Aztecs: An Interpretation, which was an audacious attempt to get inside the social and ritual processes of the Mexica (Clendinnen’s preferred and more accurate term for those commonly called the Aztecs) around the time of the 16th century. Clendinnen has both a verbal and moral clarity and restraint that is rare among writers of any sort and certainly among social scientists, and I think this was also reflected in the work she did advocating for Aboriginal rights in her native Australia.

Despite the dry title, Ambivalent Conquests: Maya and Spaniard in Yucatan, 1517-1570 is a more dramatic and linear book than The Aztecs. The book centers on the conflict between three Spaniards over colonialist approaches to the Maya in the Yucatan Peninsula, which Clendinnen reconstructs from the memoirs, letters, and other documents of the time. The tale of forced conversion, colonial power struggles, and mass torture is ghastly, but Clendinnen works carefully to contextualize these horrors in such a way that the shifting and conflicting rationales of the Spaniards do not get lost.

What does get lost is the Maya side of the story, which Clendinnen depicts as best she can in the second half of the book. But without any firsthand or even secondhand personal accounts, the overwhelming sense is of a history lost to us forever, and of peoples that can only be seen through the massive distortions of unreliable and uninformed accounts. The tragedy of that loss is palpable. Only one Maya figure, the great resistance leader Nachi Cocom, emerges as an individual, and even then only hazily.

Clendinnen begins with a quote giving one account of the mysterious name “Yucatan”:

When the Spaniards discovered this land, their leader asked the Indians how it was called; as they did not understand him, they said uic athan, which means, what do you say or what do you speak, that we do not understand you. And then the Spaniard ordered it set down that it be called Yucatan….

Antonio de Ciudad Real, 1588

This is not the only origin story of the word and not even the most likely, but it suits the story quite well, and echoes the now-disproven account of Captain Cook thinking of “kangaroo” as an animal when it really meant “I don’t know.” (The Guugu Yimithirr word is gangurru.) These Whorfian tales of linguistic relativism hold a real grip on us for neatly representing more diffuse cultural incomprehensions, and Whorfian modesty can sometimes become its own kind of arrogance, as with the case of Marshall Sahlins, or the Marxist Art & Language collective:

Clendinnen’s account doesn’t depend on theoretical relativism, however, but a very palpable and human fallibility, fueled not by ignorance per se, but by pre-conceived ideas, particularly around religion. For all that colonialism plays into this story, it is the Catholic religion and its doctrine that proves to be the largest shaping force on the three primary figures. Clendinnen’s three figures are the fanatical Franciscan Diego de Landa, hapless mayor Diego Quijada, and the humane, tormented bishop Francisco de Toral. Of these, Landa stands tallest, an overwhelming and terrifying figure of religious conviction and radiance. The Franciscans, an ascetic order ideally suited to colonizing and converting the less lucrative portions of the New World (as Yucatan was), were already a zealous order, aggressively converting the Maya to Christianity “within a context of coercion,” as Clendinnen puts it. Landa was a fanatic even among fanatics, pursuing even small offenses to their end whatever the price, and unafraid to invoke worldly and heavenly authorities alike to make his case. His conviction that he was doing good was so strong it was even able to captivate natives.

Diego de Landa

Landa’s zeal led him to learn the Mayan language perfectly, and it appears that his conviction of beatitude was able to win over many Mayans, who did not perceive that he would comfortably employ both love and torture as implements to the end of conversion. He somehow managed to befriend Sotuta chief Nachi Cocom, who had long been leading resistance against the Spaniards. Here Clendinnen portrays the two sides of Landa’s insidious personality, which allowed him to gain the trust of the Maya and access to their inner circles for the express purpose of destroying the larger share of their culture and replacing it with that of Christianity.

The intimacy of [Landa’]s descriptions – recipes favoured by the women, the antics of pet animals, the handling of babies and toddlers – imply an acceptance of the young friar into the huts and house-yards of the Maya with an easiness which goes well beyond mere nervous tolerance. He was to penetrate an even more closed zone with his admission into the society and at least some of the secrets of the elders. They trusted him enough to lament the decline in the chastity of their women from the days ‘before they became acquainted with [the Spanish] nation’.

Even more remarkably, he was shown some of the sacred writings preserved in the folding deerskin ‘books’ which were the jealously guarded, secret and exclusive possessions of the ruling lineages of each province. With Nachi Cocom, head chief of Sotuta and for so long a wily and implacable enemy of the Spaniards, he had an especially warm relationship. Landa described him as ‘a man of great reputation, learned in their affairs, and of remarkable discernment and well acquainted with native matters’ who was ‘very intimate with the author’. He recorded that Cocom ‘showed him a book which had belonged to his grandfather, a son of the Cocom who had been killed at Mayapan’. There can be no doubt that this was indeed one of the sacred and secret books of the Cocom lineage, recording its history and its prophecies. The revelation of that treasure – especially to a Spanish outsider – can only be explained as the expression of a confidence and attraction so powerful as to override traditional prescriptions and even conventional caution.

Some years after being shown these sacred books, Landa, in his official capacity and in company with his fellow Franciscans, was to burn as many of them as he could discover, together with any other sacred objects which came into his hands, precisely because they were so cherished. As he recalled in his Relación:

These people also make use of certain characters or letters, with which they wrote in their books their ancient matters and their sciences, and by these and by drawings and by certain signs in these drawings they understood their affairs and made others understand and taught them. We found a large number of these books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which there was not to be seen superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they regretted to an amazing degree and which caused them great affliction.

For the early period of his solitary wanderings, eager as he was to reveal the mysteries of his own faith, and clearly distinguishable in dress and behaviour from the Spanish soldiery the Maya had previously encountered, he had probably been identified by the custodians of Maya religion and learning as a fellow expert in those high matters. Committed to the patient accumulation of knowledge from whatever source, they can have had no notion of the exclusivist zeal which both fuelled Landa’s curiosity, and empowered him to abrogate it so decisively.

Landa became increasingly draconian whenever signs indicated that conversions and practices might not be wholly sincere, or worse, that some pagan practices might be persisting in secret. To this end he employed Inquisition methods of torture to extract confessions, hellbent on purging the impurities of his community. Clendinnen gives numbers of over 4,500 tortured and 158 dead.

Although Landa labelled it an episcopal inquisition, the enquiry bore little resemblance to established inquisitorial forms. In Bishop Zumarraga’s inquisition into Indian idolatries in Mexico between 1536 and 1543 procedures had been carefully prescribed and as carefully adhered to, and where torture was employed it was narrowly regulated. Spanish law recognised the danger of that weapon in the hands of a baffled or frustrated interrogator. In Yucatan records of interrogations were rarely kept, only sentences being routinely recorded. The penalties imposed – floggings, heavy fines, and periods of forced labour of up to ten years’ duration, and these only on lesser offenders – were well in excess of the limits laid down by the Mexican ecclesiastical council of 1555. The unashamed violence of the Franciscan inquisition is at once the best evidence for the political domination they had achieved in the peninsula, their anger at Indian betrayal, and their sense of the desperate urgency of the situation. Landa was later to justify his disregard of legal formalities on the grounds that:

all [the Indians] being idolaters and guilty, it was not possible to proceed strictly juridically against them … because if we had proceeded with all according to the order of the law, it would be impossible to finish with the province of Mani alone in twenty years, and meanwhile they would all become idolaters and go to hell …

That final line gives a sense of Landa’s desperate and fanatical sense of urgency, driven by the conviction that all around him would suffer eternal damnation if pagan practices were not weeded out. In such passages one obtains an idea of how terrifying Landa must have been. He was determined to save you, no matter what the cost. Clendinnen reads his memoirs with a searching eye, as he describes the penis laceration and animal and human sacrifice ceremonies of the Maya and how such rituals had convinced him that “only through punishment could such a people be improved.” Landa’s disgust with human sacrifice is clear, yet Clendinnen finds that “nowhere in the text [of his memoirs] as we have it is there any unequivocal indication that Maya Indians after accepting baptism had reverted to the practice of human sacrifice,” in spite of torture-induced confessions at the time presenting many accounts of such. Had Landa come to doubt the veracity of those accounts? He certainly had had none at the time, when his position and self-worth both depended on the righteousness of his cause and his ability to convince others of such.

There is nothing to indicate that Landa had any conscious doubt as to the truth of the confessions his probings had extracted from the Indians. Such cynicism is incompatible with all we know of his lofty and passionate spirit. He had known, and had known with complete certainty, the ‘truth’: the Indians were idolators, blasphemers and murderers. It had been his task and his duty to lay bare that truth. But he also knew that in performing that task he had been forced into moulding the evidence of their iniquities. He had pointed to mountains of idols as proof of the Indians’ idolatry: he knew that some of those ‘idols’ were not idols at all, but odd fragments and shards collected from abandoned sites by desperate men. He had claimed that the tortures were mild, a matter of ‘some vexation only’, but he had lived through those days of blood and anguish, and he knew that the confessions had been wrung from men in the extremes of physical agony. He had presented the confessions as true accounts, but he knew their confusions and contradictions, and what sustained pressure it had taken to get even a limited measure of coherence. Perhaps some individuals were not guilty of every charge laid against them, perhaps the ah-kines had not said precisely what witnesses had sworn they had said, but these considerations were trivial, and could not be allowed to impede him, for he knew children had died, God had been mocked, and that the Indians had betrayed him.

Landa was right, of course; the conversions were, if not insincere, certainly superficial–how could they not be under the circumstances, given that the natives recited their liturgies phonetically with no knowledge of their meaning, and that religious ceremony was taught to them shorn of most of its context? Yet Landa’s zeal interpreted this unsurprising consequence as the highest betrayal: “I save you from eternal damnation, and this is the thanks you give me?”

Mayor Diego Quijada was more or less powerless to change Landa’s course. Soon after his arrival, he wrote to the Crown about just how frightened he was of Landa:

There is in this province a friar called Fray Diego de Landa who, because I have taken this matter up, bears me ill will: he enjoys broils and having a finger in every pie, and he expects to rule in both spiritual and temporal matters. He is a choleric man, and I am afraid he will write to Your Majesty’s Council to my injury: I wish Your Majesty to understand that he has always been inflamed against those who have governed here, as he is against me … may Your Majesty never believe that I harbour ill will against him or any other man of religion, for they I support to the limit of my strength, for in their hands lies the Christian welfare of the Indians, and without them, all is in vain.

A compromising bureaucrat by nature, as well as one terrified of the Church, Quijada eventually buckled to all of Landa’s wishes. Initially trying to stem the power of the Franciscans, Quijada lost any leverage when Quijada threatened to denounce him to the viceroy. Landa then brought Quijada in as his loyal lieutenant, ordering him to torture the Maya on the government’s authority rather than the Church’s. Quiijada obliged.

There is no mention of the other Franciscans taking issue with Landa’s program. They were his men. But the settlers were perplexed and increasingly distressed by the sheer level of violence and coercion taking place around them, and the increasing likelihood of an all-out native revolt against the Spanish. Yet Landa was utterly intransigent and Quijada helpless.

Into this tense situation came Bishop Francisco de Toral, a well-regarded and fundamentally reformist Franciscan. Hardly radical, his main philosophical difference with Landa seems to have been the realization that natives would not immediately see the light and come to Jesus. For whatever reason, Toral very quickly sided against Landa and his portrayal of the natives as monstrous pagans. Toral immediately banned the practice of torture (to Landa’s objections), viewed the confessions with skepticism (to Landa’s objections), and took the colonists’ recommendation to end Landa’s investigation (to Landa’s extreme objections). Clendinnen suggests that Toral’s decision was made primarily on his judgment that Landa was a dangerous fanatic, and that he was manifestly incompetent in his position. Landa did little to contest Toral’s view, immediately marshaling all of his connections to try to discredit and expel Toral from the community. The two engaged in complicated political chess, which Clendinnen chronicles grippingly.

Francisco de Toral

Toral came to view the confessions as pure fictions, and that the torture victims had all given the same explanation for them:

they had been speaking the truth honestly before the fathers and because when they did not believe them they ordered them hoisted for the torture, they had decided and agreed among themselves that all should speak of deaths and sacrifices lyingly, as soon as they were asked about it, counselling one another and understanding that by this method they would escape the said torments and prison. And that many of those who went to make their confession came back to the prison they had left and told their imprisoned companions how they had told of many deaths and sacrifices … and that they should do the same …

But Clendinnen criticizes Toral for falling into a tendentious view of the natives just as Landa had done. Where Landa had judged them as sinning pagans, Toral, consumed by historical guilt, paternalistically came to see them as innocent victims, holy children:

Within the passage of time he became increasingly, obsessively concerned with the events of 1562. The local Franciscans had not been really ‘Franciscan’ at all, but men ‘of few letters and less charity’, lacking proper training and proper discipline. And they had suffered because of defective, indeed, criminal, leadership. Toral never wavered in his conviction of Landa’s central culpability, or that Landa’s actions had been motivated by those all-too-familiar sins Franciscans had so long struggled against: pride, cruelty, anger, and the passion to dominate.

His attitude to the Indians went through a slow transformation as his social and psychological isolation increased; as he endlessly rehearsed the injustices inflicted on them. In 1562 and 1563 he had believed the Indians to have been brutally abused by the friars, but he also believed them to have been guilty of idolatries, for which he had penanced them. By March 1564 he had transformed them into pure victims, whose idols had lain buried and forgotten until the friars unleashed their murderous rage. These poor victimised creatures were as forgiving as they were innocent:

the best people I have seen in the Indies, very simple, even more obedient, charitable, free of vices, so that even in their paganism they did not eat human flesh or practice the abominable sin [sodomy], friends of the doctrine and of its ministers even though they have killed their fathers, brothers and kinsmen, and taken their goods and put sanbenitos on them and enslaved them etc., they love them and come to them and built their monasteries and give them food and hear their masses, without reference to things past … even though when I arrived here they fled from the friars, and even though when they knew a [single] friar was going to the village everyone absented themselves from it and ran off to the bush to hide, and others hanged themselves from fear of the friars, saying they did not want to fall into their hands because they were without pity, and recommending themselves to God the poor miserable ones hanged themselves, pitiable as that is to say and to hear.

So Toral constructed the intelligibility of ‘history’ out of the confusion of experience, making unambiguous shapes out of the threatening ambiguities of Franciscians who did not act as Franciscans; of Indians who were tormented victims and yet who also worshipped idols.

Clendinnen is drawing an epistemological equivalence, not a moral one. (I initially felt her to be overly harsh on Toral.) Both Landa and Toral created reductive pictures of the natives that obscured the truth rather than aid in revealing it.

Historians, particularly those of a somewhat rightist bent, have tended to treat the confessions obtained by Landa as legitimate. While not ruling out the possibility of some ongoing sacrifices, Clendinnen concludes that the confessions were generally inflated when they weren’t concocted. She gives several ingenious piece of forensic analysis for her view, of which this is the most impressive:

if each piece of information in each confession is tabulated – a tedious process, although made easier by the formulaic sequence of questions put by the interrogator – an intriguing pattern is revealed. (Here the analysis depends on sequence, and assumes the testimonies to have been taken in the order in which we have them, but internal evidence supports that assumption.) To take the confessions of Indians from Sotuta village recorded on the first day of the enquiry: what we find is a high degree of concordance between the first and third confessions, and between the second and the fourth – although the fourth also incorporates some fragments from the first and the third confessions. This pattern is completely compatible with the Indians’ claim that each witness when returned to the gaol strove to recollect what he had said, which material was discussed by the others, but which could not benefit the next Indian taken immediately for the recording of his confession. Again, in the Usil testimonies we find the same pool of names of victims being drawn on by different witnesses, although ascribed to different sacrifices, while the last witness from Tibolon drew on the names provided by the witness questioned before him, but distributed them differently.

In other words, desperate to extract themselves from the ongoing torture regiment, the imprisoned Maya schemed to give the interrogators what they wanted.

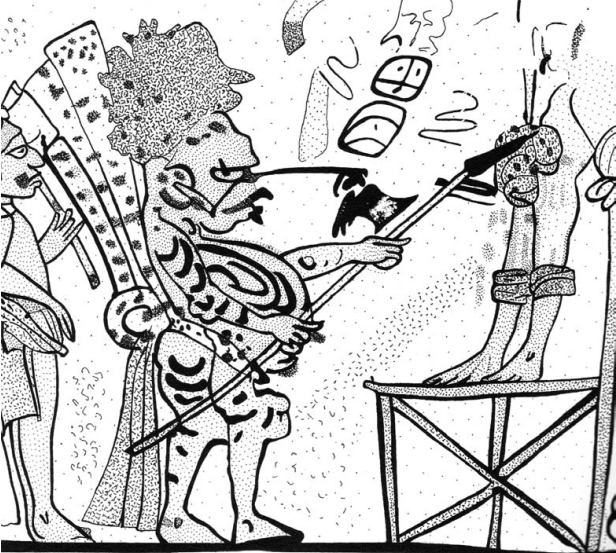

Clendinnen does not mince words about what Maya sacrifices entailed. She recounts the one extant description of such a ritual with an accompanying warrior chant:

A noble war captive, naked and painted blue, the colour of the sacred, was brought with procession and dance to an open space, and tied to a column. An ah-kin then wounded him in the genital area, so that the genital blood began to flow – as it did in the many penis-laceration rituals of the Maya – while circling, dancing warriors shot arrows at him in controlled sequence. Landa claims they aimed for the heart, implying a test of markmanship, ‘to make his chest one point like a hedgehog of arrows’, but the chant suggests rather different actions and intention:

make three fast turns

around the column of painted stone

there where the virile youth, unstained, undefiled, a man, is bound.

Make the first, and on the second turn

take up your bow, fit the arrow to the string.

Aim at his breast. It is not necessary

to use all your force

when you let fly, so that his flesh

will not be too deeply wounded.

Let him suffer little by littleThe victim will not only suffer. He will bleed. The intention was not to kill, but to wound delicately, to pierce the skin and flesh so that the blood springs forth. It is likely the Maya understood the whole action not so much as the offering of a human ‘life’, but as the presentation of a noble spectacle; of a substance of great fertilising power, as blood, especially genital blood, was understood to be.

For Landa, such practices demanded salvation for their practitioners by any means necessary, and had no meaning beyond the huge marker of “sin.” For Toral, they were irrelevancies next to the injustices perpetrated on the entire people of this culture.

Mayan human sacrifice

The Maya had historically tortured their own captives as well, though for ritualistic reasons rather than as a tool for extracting confessions. In the Mayan world, defeated warriors were dehumanized, enslaved, or sometimes sacrificed. I don’t intend to go down the rabbit hole of passing moral judgment on Mayan culture. Any society foreign to our own is likely to have beliefs and rituals which we will find repugnant or even outright evil. Certainly both that of the Franciscans and the Maya possessed them. The ongoing question of where one draws the line of judgment is likely never to be resolved, but Clendinnen deserves great praise for exercising a great deal of perspective and restraint in her chronicle, presenting reasons rather than judgments. Her shaping no doubt evinces a desire to make clear the extent of the barbarous practices of the Franciscans and of Landa in particular, but every side is given space to give their case, even if some are baldly unconvincing. It seems many historians trust readers less to make such judgments these days, prescribing instead the proper views and reactions to the events they chronicle. But loud moralizing will not only look badly dated as views of what is proper evolve further, it also treats the readers as children, and we should not be surprised if people treated as children only know how to act like children. For me, I think that judgments about which society was “better” are meaningless, but also that it is Landa’s heritage, the heritage of the Spanish and the conquered, that won out and which helped birth society as we know it today. It is the one which merits closest examination for what dangers it may still pose, just as the Mayan heritage (what little we have of it) merits examination for the contrasts and commonalities it offers to us.

Benny Shanon is an Israeli cognitive psychologist who has taken the psychoactive hallucinogen ayahuasca well over one hundred times. His book The Antipodes of the Mind: Charting the Phenomenology of the Ayahuasca Experience is a scholarly attempt to describe its effects both through a survey of participants and through descriptions of his own extensive experiences.

Benny Shanon is an Israeli cognitive psychologist who has taken the psychoactive hallucinogen ayahuasca well over one hundred times. His book The Antipodes of the Mind: Charting the Phenomenology of the Ayahuasca Experience is a scholarly attempt to describe its effects both through a survey of participants and through descriptions of his own extensive experiences.