The object of hope is an apparent good; the object of fear, an apparent evil. Whence the hoped-for good that is expected to come to us we never perceive with security; for if we so perceived it, it would then be certain, and our expectation would more properly be called not hope, but joy. Even the most insubstantial arguments are sufficient for hope. Yea, even what the mind cannot truly conceive can be hoped for, if it can be expressed. Similarly, anything can be feared even though it be not conceived of, provided that it is commonly said to be terrible, or if we should see many simultaneously fleeing; for, even though the cause be unknown, we ourselves also flee, as in those terms that are called panic-terrors.

On Man 12.4

Waggish

David Auerbach on literature, tech, film, etc.

Tag: politics (page 11 of 15)

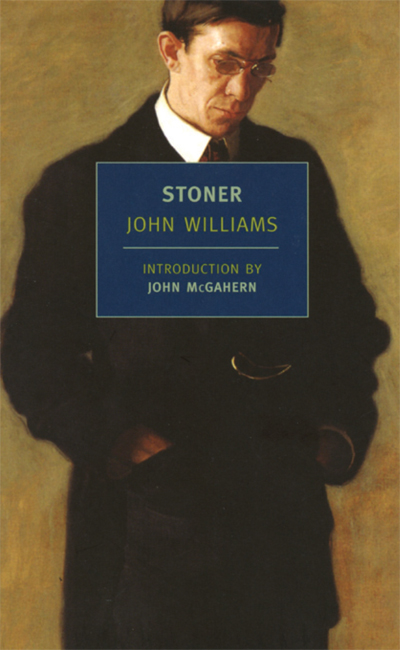

Whatever my reservations about the New York Review of Books, if it subsidizes reissues of things like this, I pardon its sins. Extra points for choosing such an apt cover painting to implicitly portray its hapless professor hero:

And here is Stoner speaking:

Stoner looked across the room, out of the window, trying to remember. “The three of us were together, and he said–something about the University being an asylum, a refuge from the world, for the dispossessed, the crippled. But he didn’t mean Walker. Dave would have thought of Walker as–as the world. And we can’t let him in. For if we do, we become like the world, just as unreal, just as…The only hope we have is to keep him out.”

Walker is an ignorant, smooth-talking, careerist academic, and there’s little separating his portrayal in this book (from 1965, but taking place mostly in the first half of the century) from these sorts of people today. Stoner is an impractical dreamer, a farmboy who goes to a local college and discovers he loves literature, and so does his graduate work at the same school and then gets a professorship there. He makes two mistakes: he marries the wrong woman, and he makes the wrong enemy in his department. These are big mistakes, and he pays big for them.

I cannot recall any other academic novel that treats its subject material with such unremitting gravity. The standard model of an academic novel is to either indulge in high melodrama (Mary McCarthy, Iris Murdoch) or to make light of the intellectual pretenses of its characters (Kinsley Amis’s overrated Lucky Jim, Malcolm Bradbury’s far funnier Stepping Westward). Williams’s approach seems to have been to adopt the social realist approach of George Gissingand Sinclair Lewis’s more sober moments and apply it to the incongruous and hermetic world of a university. Consequently, he treats the small events of Stoner’s life with a sense of real consequence, as though they were matters of life and death. And so they become.

After his mistakes, Stoner is a defeated man, and it takes him years to recover. But what saves the novel from being just an exercise in misery is that Stoner does get his triumph. He fights against the inertial decline of his life, and he wins. It is, objectively speaking, a small triumph, but on the terms that Williams has set, it validates his existence without qualification. The novel is a passage from ideals that cannot be fulfilled to a non-tragic view of life, and it’s summarized best in this passage:

In his extreme youth Stoner had thought of love as an absolute state of being to which, if one were lucky, one might find access; in his maturity he had decided it was the heaven of a false religion, toward which one ought to gaze with an amused disbelief, a gently familiar contempt, and an embarrassed nostalgia. Now in his middle age, he began to know that it was neither a stae of grace nor an illusion; he saw it as an act of becoming, a condition that was invented and modified moment by moment and day by day, by the will and the intelligence and the heart.

I don’t mean to downplay the brutally accurate portrayals of academic politics and fleeting trends, which feel absolutely au courant, but the novel would not stand out as it does if it did not treat its subject matter with the same respect and humility with which Stoner himself treats literature and teaching.

Here I was about to write on Dante, and I hear that Rorty has passed away. Rorty is such a paradoxical and multifaceted figure that his death gives me cause to ponder my own philosophical orientations and biases. Even more than other analytic “slipstream” figures (my appropriated, tongue-in-cheek term for those analytics who headed, intentionally or unintentionally, towards an epistemological and hermeneutic rapprochement with continental developments: late Wittgenstein, Quine, Sellars, Goodman, Putnam, Davidson, McDowell, and Brandom, all of whom owe some kind of debt to the American pragmatists, particularly Peirce), Rorty let himself abandon the analytic style and rigor and embrace far more historicist positions. And I feel this pull myself. But complicating this is the seeming existence of three Rortys. In roughly chronological order:

- the analytic “linguistic turn” Rorty (Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, etc.)

- the pragmatic deconstructionist Rorty (Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, etc.)

- the liberal populist Rorty (Achieving Our Country, late essays, etc.)

Even worse, the earlier Rortys continued to coexist with the later ones, although the analytic Rorty disappears mostly from the picture post-Contingency. The reason for this vanishing is that Rorty wisely realized that the post-Sellarsian philosophy of language was neither useful nor supportive of the relativistic pragmatic liberalism that the other two Rortys wanted to promote. Between the first two Rortys is Rorty turning his back on the analytic tradition and collapsing the lessons of Sellars and Quine into a roughly deconstructionist stance that Rorty inherits from Derrida, as well as an explicit embrace of historicism. There is little talk of sensing, mind, or language as practice in his later work, though clearly Rorty maintained enough affinities with his analytic forefathers to acutely criticize post-Kripkean analytic metaphysics. I am in great sympathy when in that article, he observes, criticizing Kripke-worshiper Scott Soames:

To my mind, the story of 20th-century analytic philosophy (including the role of Kripke in that story) is best told by highlighting questions about whether truth is a matter of correspondence, about what is and is not ‘out there’ to be corresponded to, and about whether there is any sense in which thought makes ‘direct contact’ with reality. So I regret that Soames’s history shoves these issues into the background. But perhaps correspondence is just my hobbyhorse, as necessity is his.

Couple “language” with “thought” and “truth,” and this is indeed my view of modern analytic philosophy as well. But even as he says this, his later work makes it clear that Rorty had lost interest in this question in and of itself, and was far more concerned with its implications and utility in political and cultural frameworks. His leap to an embrace of continental traditions is not surprising in this light, and his status as a maverick seems to be mostly due to this leap alone. His actual positions fit squarely into a deconstructionist (or “post-structuralist,” if you will) mainstream, with a little American flavoring. With regard to his treatment of meaning and language, Rorty’s actual separation from Derrida lies less in his ideology and more in the comparative clarity of his writing, which did as much to offer analytics a bridge to deconstructionist thought as it did to antagonize them towards it.

Perhaps it was this clarity that caused the third Rorty to evolve, in which he popularized his style even further and, most notably, wrote a little book called Achieving Our Country, celebrating Emerson and Dewey as models for a pragmatic politics. No matter that much of what he advocates in this book is unsubstantiable by Rortys 1 and 2. It was clear that after having embraced a heterodox liberalism under the guise of “liberal ironism” in his second incarnation, he was ready to put that into practice and drop the theory to attempt a concrete politics in the tradition of Dewey. Yet while Habermas attempted to ground such a liberalism in a dense, coherent account of intersubjectivity, Rorty seemed to have lost interest in fighting with other philosophers, and wanted to speak to the people. The book was not popular, though it earned an amusing rebuke from George Will in Time, who must have seen it as some sort of threat, or as a convenient strawman for attacking academia. That last point is particularly ironic, as Rorty #3 did indeed drop (or at least obscure) all of the relativist baggage that David “Black Panthers and Blacklists” Horowitz thinks threatens our nation. Some good it did him. In the late essays published (by Penguin!) in Philosophy and Social Hope, he is attacking Marx and criticizing philosophical leftists like Derrida for embracing Marxism, in between celebrating Forster and (again) Dewey.

Ironically enough, I see something of a parallel development in Derrida, who begins as an unorthodox but traditional Husserlian phenomenologist, then develops an aggressive deconstructionism in contrast to preceding structuralist trends, and finally ends his life advocating for the EU and Enlightenment values and making nice with arch-enemy Habermas in the name of liberalism. But Derrida never quite abandoned his audiences the way that Rorty 1 and Rorty 2 did.

II.

There have been countless accounts of analytic vs. continental personalities, and I only offer this one on the

grounds that it’s purely anecdotal. (I use “continental” here as shorthand for the poststructuralist mainstream that holds sway in America: Derrida, De Man, Foucault, Kristeva, Lacan, Agamben. No need to correct me on this point; I know.) But my experience has been that on assuming a position, analytics are far more likely to take it as truth to be put into practice, while continentals tend to embrace a position as justificatory rhetoric. For instance, the analytic incompatibilist determinists I know, who believe in no free will and no moral responsibility, seriously apply such beliefs in their daily lives: they picture people as robots to be corrected when they malfunction, and they have no patience with even the idea of revenge. Derek Parfit’s views on (lack of) personal identity, by his own admission, brought him great comfort in facing death. David Lewis, to cite an extreme example, truly believed in an infinite number of alternate worlds for modal purposes. (Indeed, another modern history of analytic thought could be the effect that rigidity can have in inflating pedantic disputes into highly unintuitive beliefs.) On the other hand, the continentals I’ve known have been far more likely to stick with what is, in effect, a foundationalist standpoint, and use philosophical works, appropriately or otherwise, to justify them. I have seen many continentals discourse on the indefinite postponement and deferral of truth and meaning, only then to proclaim the moral evil of the Enlightenment, capitalism, the United States, Europe, etc. One could blame Heidegger for being especially bad at this, but my unjustified suspicion is that the indifference to rhetoric falls out of the modern continental approach itself, just as the analytic approach produces its dogmatists. For whatever reason, Rorty’s “irony” came to dominate his view to the point that such a serious embrace of analytic metaphysical positions became anathema to him. Yet because he was in America or because he was outside the continental scene or because he just was like that, he failed to feel the urgency to dive into the continental pool.

Many of the figures mentioned above, despite my complaints, were brilliant and did remarkable work in analytic or continental philosophy. I think Rorty will be remembered for pursuing a more aggressive synthesis than most more than for espousing a particular position. I don’t necessarily see this as a fault, because I think his intent ultimately was not to stake out a singular philosophical position, but it does complicate how to assess his stature. Maybe because I am something of a philosopher, I can’t think of him as being as important as Habermas, Davidson, or even Derrida, even though I have problems with all three of them. If Rorty had had another fifty years, perhaps he would have produced a big book that would have been a liberal, anti-communitarian version of Alasdair MacIntyre’s After Virtue; more likely, though, he would have gotten involved in politics (as another of his spiritual compatriots, Charles Taylor, actually did). He would have made a good columnist for the New York Times, certainly a better one than the universally ridiculed Stanley Fish. (But there I go, shooting Fish in a barrel again….)

Q: You are Chilean, Spanish or Mexican?

A: I am Latin American.

This is a long book–too long, in fact–but it makes its point. Bolano, who died a few years back as a consequence of alcoholism, drug abuse, and assorted other consequences of extreme living (read the New Yorker profile of Bolaño for an overview), wrote a lot of short books and two very long books, including this one. And not only does it play at being autobiography, but also at a bildungsroman, as it follows “Arturo Belano” and his friend Ulises Lima from Mexico to Europe to Africa. But given Bolaño’s life, it reads as the only bildungsroman he could have written: a paean to the costs and benefits of never growing up. The bildung is entirely ironic, or negative.

The setup, in the words of James Wood:

“The Savage Detectives” was published in 1998, but its heart belongs to the Mexico City of the mid-1970s, when Bolaño was an avant-garde poet bristling with mad agendas. Like much of his work, the novel is craftily autobiographical. Its first section is narrated in the form of a diary, by a 17-year-old poet named Juan García Madero who is on the make, erotically and poetically, and who has been asked to join a gang of literary guerillas who have named themselves the “visceral realists.” The group is led by two young poets, Arturo Belano and Ulises Lima, a wild duo who appear elsewhere in Bolaño’s work (in “Amulet,” for instance). Lima is based on one of Bolaño’s friends, the poet Mario Santiago, and Belano is based on … Bolaño.

Yet for this scenario, there isn’t a lot of literature in the book. Much of the so-called literary discussion is nothing more than trivialities, like Garcia Madero quizzing his friends on obscure poetic terms, and so-called “visceral realism” is, it is made clear, a mere platform for attacking the many betes noires of Lima and Belano (and Bolaño), particularly Octavio Paz and Pablo Neruda. Bolaño never slips: the book is entirely committed to showing literature as a lifestyle and not as an artwork, and what it extracts.

Much has been made of the book’s structure, and justifiably so. It is sandwich-shaped, with two shorter bookends taking place in 1975 and 1976 of the diaries of Juan Garcia Madero, and the main section narrating events episodically from 1977 to 1996 with intermittent flashbacks to 1976. The first section shows most of the benefits of the characters’ lifestyle, and it is not without some irritation that I read through one hundred pages of Juan sleeping his way through his fellow women poets and talking big with his fellow male poets. This irritation is intentional, because when things of consequence start happening, they are exactly the product of the sort of indulgent childish lives of wastedness that the visceral realists have been living. The rest of the book details the costs.

Even in that first part, we don’t forget that they are children: the visceral realists are people in their late teens and early 20s. Even Belano, who was imprisoned by Pinochet’s government in Chile after the coup before returning to Mexico, treats his experiences in the detached, solipsistic way a writer would: his politics are vague and more visceral than intellectual. The Chilean experience is only alluded to, while the book slides into a soap opera plot about Belano, Lima, and Garcia Madero going on the run with a girl trying to escape from her murderous thug boyfriend. If this sounds dissonant in summary, it doesn’t on the page, but it is terribly disconcerting, when the soap opera seems more real than Allende and Pinochet. So it is with adolescents. Bolaño hardly shied away from political topics, embracing them explicitly in works like By Night in Chile, but here he intentionally resists them because they are at odds with his characters and subject matter, and this is part of the tragedy he is trying to convey.

We return to the soap opera of 1976 at the book’s end, after having seen Belano disappear into civil war Liberia after nearly getting killed there, having stopped drinking due to a liver ailment that has doomed him to an early death (as one did Bolaño, killing him in 2003). Yet there hasn’t even been a progression during the middle section, and this is significant. Scenes from 1976 keep acting as a magnetic attractor as the other recollections move forward in time, arresting any sense of forward progression. Since the middle section of the sandwich is so diffuse, containing recollections from dozens of characters who never recur, many of who only had the most tangential interactions with Belano and Lima, no robust narrative emerges as a counterweight to Garcia Madero’s diary, and Garcia Madero himself is definitively absent from the middle section. The overall sense is that indeed, all of these characters’ lives ended in 1976, as Garcia Madero’s seems to have, and what is playing out afterwards in the middle section is a kind of afterlife purgatory of the sort Alasdair Gray brilliantly portrayed in the last two books of Lanark: a purgatory in which the characters wander lost without development. It is in this way, and no other that I can find, that the book makes sense, and a fatalistic, depressing sense indeed.

There are moments in the book–only moments–where the priorities change. The first is the horrific story of Auxilio Lacouture who hides in a bathroom for almost two weeks while the Mexican Army occupies her university in 1968 (she recounts this in late 1976 in the forward timestream of the book). She proclaims herself “the mother of Mexican poetry.” In the language of the book, this means that she, like Garcia Madero, disappears completely after 1976. Bolaño does not call attention to her disappearance, but it is crucial for the narrative that she vanish from the book: she represents the mother of all that is damaged and cannot survive. (It is at this crucial episode, however, that Bolaño’s writing falters, as Auxilio talks like a man, as happens with many of his most significant female characters.)

The other moment is the Liberian civil war, and it must be there that Belano vanishes, because it is there that his childhood truly runs out, as he seems to be faced with something he cannot comprehend.

And yet, Bolaño has stacked the deck, for Belano gets divorced and does not have children; Bolaño remained married and had two children. Belano lives on alone, near-suicidal in his excursions. Bolaño escaped, but for the sake of the narrative of Latin American and Latin America’s writers, Belano is sacrificed. The pathos is complete.

I am not in love with Bolaño in the way that Matthew details in his entry on Bolaño. As the work of a man who was racing against time to produce something urgent and vital, it is appropriately striking and direct. But The Savage Detectives, for all its careful construction, doesn’t quite have the juice to justify its conceit: Bolaño doesn’t quite manage to complete the circle to link Belano’s adventures in Liberia to the final 1976 episode with Garcia Madero. And the very end of the book, rather than making excuses, appears to acknowledge exactly that incompletion. Bolaño proclaims the imperfection of his work, and implies that perfection has gone to death with all his young characters. While not a satisfying ending, it is one I accept.

Genealogically speaking, this book isn’t as captivating as Hirschman’s The Passions and the Interests, because it’s not a survey of past rationales, but an analysis of contemporary behaviors in response to this phenomenon:

Firms and other organizations are conceived to be permanently and randomly subject to decline and decay, that is, to a gradual loss of rationality, efficiency, and surplus-producing energy, no matter how well the institutional framework within which they function is designed.

Free of the meta-analysis, Hirschman doesn’t manage the ideological sweep of the other book, but there’s enough here that should interest even the most impractical humanities scholar. (Like the other book, this one is very short.) Hirschman’s structure is simple: when employees or consumers of an institution are faced with decline of how that institution serves and services them, they either vocalize their grievances (“voice”) or they vote with their feet (that would be “exit”). Various constraints make one option more attractive than the other, and sometimes exit isn’t available, or voice is minimized. There are two scenarios in particular, one conceptual and one historical.

The first is Hirschman’s free-market apostasy in saying that competition can work against voice, since the more vocal and less vocal can be separated into equally impotent factions. The easily dissatisfied ping-pong between equally bad options while the more inertial sorts stick around and don’t complain, giving no incentive for the institution to improve. (Think cell-phone companies.) This plays itself out in a more class-stratified way if there is a better but more expensive option for the privileged class to exit towards, leaving the less empowered stuck with a system that again has fewer incentives to change. (Think public and private schools.) Under orthodox conceptions, this is no prisoner’s dilemma, as the free-marketer would expect any exit to motivate the institution to improvement. In actuality, the institution will often be glad to be rid of these complainers. Sometimes it’s because they weren’t worth the trouble, but often it reinforces existing resistance to the troublesome process of reversing decline. One look at the sociologically fascinating Mini-Microsoft reveals a handful of salutary problems facing Microsoft in decline:

- Many of the most creative and most vocal leaders and employees have already left.

- Those remaining are miserable.

- Because of the first factor, the company has less incentive to address the second.

- The company’s attempts to stem the damage are perceived as cosmetic, and because of the above reasons, probably are.

- Remaining executives are perceived as not being accountable in the slightest and cashing in.

- If the increasingly livid tenor of the comments is any indication, things are getting worse, not better.

Mini-Microsoft is a particularly interesting case because even though the remaining employees are an extremely vocal and articulate bunch, the exit behavior appears to have caused a backlash demoralizing both executives and low-level employees. Hirschman’s optimistic suggestion that voice be recognized before things decay to this point seems unrealistic, however, since it requires a foresight that no institution can be expected to have: why listen to people gripe when everything is fine? I fear that only the absence of exit makes voice truly viable, and that is only because the possibility for organized, open revolt exists when those first exiters aren’t able to leave.

Point two: the United States was founded on exit, grew through exit, and exit is ingrained in its psyche. Founded by those who voted with their feet, grown on cheap immigrant labor, expanded through pioneer expeditions, and granted the luxury of isolationism through geographical position, the country has been notably reticent to address complainers, and the massive backlash against civil rights and entitlement programs is only one of the more distasteful examples. Complaint is frowned upon precisely because of the “If you don’t like it, go to Russia” ethos:

Why raise your voice in contradiction and get yourself into trouble as long as you can always remove yourself entirely from any given environment should it become too unpleasant?

Ironically, this book was written in 1970, so Hirschman cites the black power movement as a notable exception to this trend. Forty years later, a singular, failed exception it remains.

I have not spent enough time with other cultures to have a sense of how distinctively American this trait is, but people from Tocqueville to Veblen to Richard Hofstadter have remarked on it, so I’ll assume it’s at least more extreme here. It makes me wonder if the comparative absence of politically-engaged novels and works of philosophy in U.S. history (note that I am talking about political engagement rather than agitation and muckraking, so I don’t count Dreiser, Upton Sinclair, and Sinclair Lewis, nor the disenfranchised voices of Baldwin, Ellison et al.; Dewey is a notable exception, however) can be traced not only to individualism, but also to the disparagement of voice in our culture. Do we teach our writers to stay the hell out of politics? Is that why our supposed politically-engaged writers (Mailer, DeLillo, Franzen) are such a joke?

© 2025 Waggish

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑