I do not ever know if it is my good spirit or my evil spirit that speaks these words within me. But it simply has to get out.

Since I awoke to life I have always seen things in an “other” way. That means: in places, clear criticism, in places, clear suggestions, well thought through. Some I have written down and published. But much more has remained at a level of dark antipathy. Half raised up, then sunk down into obscurity. Intuition sensing far-reaching connections that the understanding has not followed.

The understanding that has had the benefit of scientific training is loath to follow if it has not been able to build itself bridges for itself whose load-bearing capacity is calculated exactly. Here and there I completed the calculations for a single area of such a bridge; dropped the work again in the conviction that it is not possible, after all, to finish it. I could sit down and gather material in the way that it has been done in similar assiduous, large scale experiments — Wundt, Lamprecht, Chamberlain, Spengler.

But what remains when this is done? When the breath has evaporated with which one tried to bring such fullness to life, there is nothing but a dead heap of inorganic material.

The five-year-long slavery of the war has, in the meantime, torn the best piece from my life; the run-up has become too long, the opportunity to summon up all my forces is too short. To renounce or to leap, whatever then happens, this is the only choice that remains.

I renounce any systematic approach and the demand for exact proof. I will only say what I think, and make clear why I think it. I comfort myself with the thought that even significant works of science were born of similar distress, that Locke’s. . . . are in fact travel correspondence.

I want to develop an image of the world, the real background, in order to be able to unfold my unreality before it.

Robert Musil, Notebook 19 (1919)

Waggish

David Auerbach on literature, tech, film, etc.

Tag: modernism (page 2 of 7)

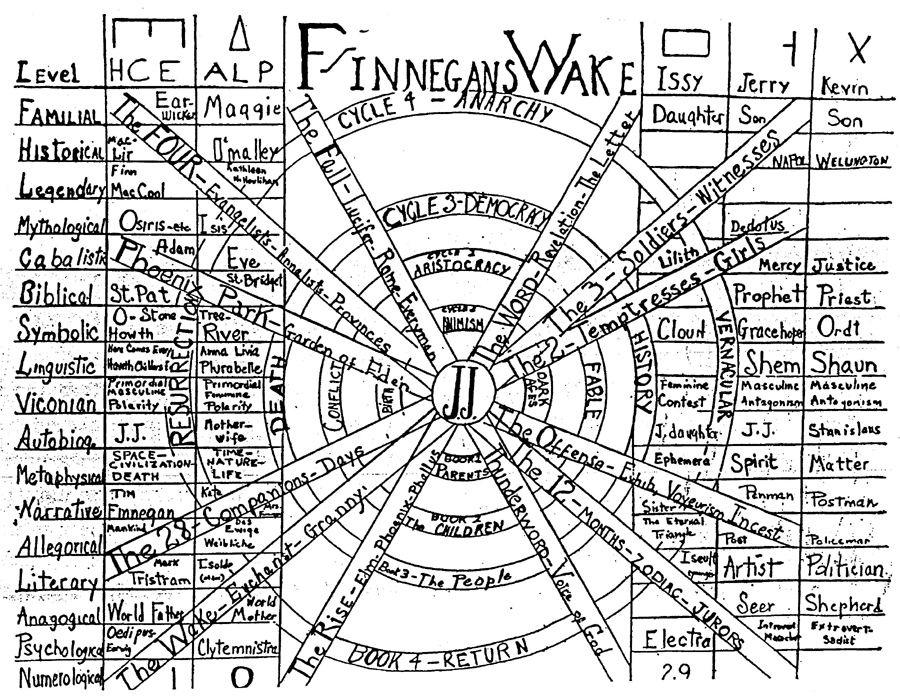

James Joyce made the superimposition of conflicting patterns one of the central principles of both Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. (You can see it in Portrait as well, but nowhere near to the extent.) While he drew on Dante’s schematic cosmology as a model for organizing huge and diverse amounts of material, he drew from Shakespeare the notion that uncertainty, indeterminacy, and outright contradiction could give immense strength and depth to the effect of a work on readers.

Unlike Shakespeare, Joyce could not hide his life from his readers. People were now far more interested in the life of the artist, and documentation was too easily had. But rather than trying to mask his intentions, he could overload a work with as many conflicting and indeterminate moments, motifs, and significations as possible. Schemata that came to mind after the basic construction of a work, like the infamous Ulysses schema that Joyce gave to Stuart Gilbert that has held too much sway ever since, were just additional bricks to add to the consternating edifice. (Note the somewhat variable Linati schema.)

This gave rise to the peculiar modern criticism that Joyce does not say anything. Harry Levin was both perceptive and naive in 1939 when he reviewed Finnegans Wake and said:

Among the acknowledged masters of English—and there can be no further delay in acknowledging that Joyce is among the greatest—there is no one with so much to express and so little to say. Whatever is capable of being sounded or enunciated will find its echo in Joyce’s writing; he alludes glibly and impartially to such concerns as left-wing literature (116), Whitman and democracy (263), the ‘braintrust’ (529), ‘Nazi’ (375), ‘Gestapo’ (332), ‘Soviet’ (414), and the sickle and the hammer (341). The sounds are heard, the names are called, the phrases are invoked; but the rest is silence. The detachment which can look upon the conflicts of civilization as so many competing vocables is wonderful and terrifying. Sooner or later, however, it gives a prejudiced reader the uncanny sensation of trying to carry on a conversation with an omniscient parrot.

Harry Levin, “On First Looking into Finnegans Wake” (1939)

The rest is anything but silence. Joyce was aware of the implications of all of these terms (and was hardly impartial about them). He created breathing space not by failing to elaborate on these terms, but by invoking as many associations with them as possible, fully aware of their contradictions.

This sort of technique agglomerates into daunting complexity, but I don’t think the method is meant to complex, nor did Joyce intend it to be. It doesn’t need to be complex for striking effect. One very central opposition/superimposition is the idea of linear and circular motion. Joyce conflates the two very frequently in both Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. The very basis of Ulysses, a single day, is a canonical example: at the end of the day, one cyclically returns to where one started, while having progressed linearly to a new day. Likewise, Odysseus returned home on a circular journey while experiencing the linear movement of plot. Very simple.

But Joyce also applies the device repeatedly at a lower level. (I hesitate to use the dread word fractal, but it’s appropriate in this case.) The novel is constructed in a symmetrical form: 3 chapters, then 12 chapters, then 3 chapters. Yet the mapping of the styles individual chapters in the first and final sections is not done in reflection:

- Chapters 1 and 16 (Telemachus and Eumaeus): third-person narration.

- Chapters 2 and 17 (Nestor and Ithaca): interrogative dialogue.

- Chapters 3 and 18 (Proteus and Penelope): first-person interior monologue.

And yet chapter 1 was given the sobriquet “Telemachus” rather than chapter 3, which would make more sense given this parallel, as Stephen is Telemachus and Molly is Penelope. But it would wreck the larger symmetry of having a book called Ulysses that begins with Telemachus and ends with Penelope. Joyce had no problem with breaking patterns for the sake of establishing other patterns.

Likewise, the middle 12 chapters divide into sets of 3, with every third chapter (6, 9, 12, 15–Hades, Scylla and Charybdis, Cyclops, Circe) having a Big Plot Event, conflict, or climax relative to the remaining, somewhat more subdued chapters, even as the style and material of the chapters is continually progressing into new and generally more abstruse territory. The “squaring of the circle” theme that preoccupies Bloom is also a reflection of how the linear is coextant with the cyclical, but not identical. There are many, many other instances.

And I think that this fundamental overlay of linear and cyclical remains, more or less unaltered, in Finnegans Wake. I believe it to have been a fundamental component of Joyce’s metaphysics and cosmology, and I believe that Vico was primarily a way for Joyce to obtain a central cyclical structure for history. Richard Ellmann quotes Joyce as saying, when asked if he believed in Vico’s New Science, “I don’t believe in any science, but my imagination grows when I read Vico as it doesn’t when I read Freud or Jung.” The content of Vico’s cycle, while useful, was less crucial than its form.

But even though Joyce gave Finnegans Wake a clear cyclical structure by having its first sentence complete its final sentence, the linearity is there everywhere as well, from Jaun’s evolution, journey, and quest narrative in the third part to the very process of children growing up and defeating/killing/usurping their father. The one-way journey from birth to death, from child to adult, is neither trumped nor negated by a cyclical view of history. (Perhaps it’s only in infinity that endless similar recurrences of a process can result in occasional identical instantiations of that cycle; again, think of the squaring of the circle, which would only be possible in infinity.) If the cyclical aspect seems overly pronounced at times, it’s only because the linear aspect is so often the default.

The timescale of the book works similarly. Two of the timescales in the Wake is from 6pm to 6am and sunset to sunrise. Sunset and sunrise are mirror reflections in time and in space, but the sun’s one-way motion across the sky accounts for it rising in the east and setting in the west, it having made a reverse journey to return to its place of origin while maintaining forward motion, by virtue of the extra dimension. The half-revolution of the Earth covered by this time period covers exactly half the journey, 180 degrees, from one linear extreme to the opposite, before reversal toward the point of origin begins.

Joyce also used the Egyptian Book of the Dead as a foundational text for Finnegans Wake, and Egyptian mythology has a near-perfect analogy for this process. In Egyptian mythology, Ra the sun god dies at the end of each day in the west and makes a journey through the underworld each night to return to the east, where he is reborn. (He makes the journeys on boats, no less, allowing for Joyce to fit in the female aspect as the water.) This fits uncannily with Joyce’s ever-reborn masculine, eternal feminine, and the identification of the day-night cycle with that of life and death, rise and fall, civilization and breakdown.

The motion motifs pile up to immense complication, since Joyce works this superimposition in at many levels. One combination of circular and linear motion then becomes part of a larger series of circular and linear motions which can reflect, mirror, or reiterate the original combination; and so on and so forth. Joyce makes much hay of reflection, mirrors, symmetry and asymmetry, twins and opposites, and so on.

Appreciating this complexity does not require seeing all these superimpositions or even most of them. Joyce knew this would be impossible for a reader or even a group of readers, so he chose an approach that would demonstrate this near-infinity of superimpositions through a fundamentally simple method that could organically grow into immense complexity. This creates the secular sense of awe that Joyce inspires in me. I see it as Joyce’s ultimate expression of the attempt to comprehend the metaphysical infinite with the finite resources of the mind and portray it in art.

Richard Ellmann, in his biography of Joyce, quotes a passage of Benedetto Croce, which Joyce had certainly read, that is quite apt:

Croce’s restatement of Vico, ‘Man creates the human world, creates it by transforming himself into the facts of society: by thinking it he re-creates his own creations traverses over again the paths he has already traversed, reconstructs the whole ideally, and thus knows it with full and true knowledge,’ is echoed in Stephen’s remark in Ulysses, ‘What went forth to the ends of the world to traverse not itself. God, the sun, Shakespeare, a commercial traveller, having itself traversed in reality itself, becomes that self…. Self which it itself was ineluctably preconditioned to become. Ecco!‘

[Introductory note: this is a very old paper. It strikes me now as immensely callow in voice and construction, yet I don’t find it too embarrassing. I think this is because Kafka is very receptive to the sort of motivic analysis that I perform here, so I had a wide margin for error. So even if the conclusion and narrative are reductive, the links are still meaningful. My mistake was in trying to draw too definite a theme from them. It could just as easily have been called “The Fluidity of Spaces,” but “The Stasis of Spaces” just sounds so much better and reminded me of Georges Perec’s Species of Spaces (that would be Espèces d’espaces in the original French). I’ve resisted the temptation to make stylistic edits, so please enjoy some juvenilia. I remember, more than anything, really enjoying writing it, and maybe that redeems its faults for me now.]

The Door that Always Stands Open

In Franz Kafka’s The Trial, K. makes his way through a labyrinthine and chaotic city in dealing with his case. He is continually entering and exiting doors, going through passageways, and passing through antechambers. The ubiquitous presence of doorways is immediate and constant. Yet the doors in The Trial do not function as normal doorways; the spaces that they separate are not entirely separate. In the course of the novel, Kafka dissolves the clear delineation between the two sides of the door, and creates instead a space within the door, which is central to the entire narrative of The Trial, both in relation to the spaces of the city, and in relation to time.

In a nearly physical example of this dissolution, a door virtually disintegrates as young girls mount an attack on it, in the “Painter” section. Titorelli remarks that the girls have “had a key made for my door, and they lend it round” (144), already hurting the door’s function to keep people on one side of it. The row of girls becomes a constant force against the door. They “see into the room through the cracks in the door” (148) as they crowd around the keyhole, and they then breach the door with their words. They breach the door physically, by thrusting “a blade of straw through a crack between the planks and . . . moving it slowly up and down” (150). The painter even remarks that “the air comes in everywhere through the chinks [in the door]” (155). When the girls are once more “crowding to peer through the cracks and view the spectacle” (156), the door seems hardly there, not functioning as a physical boundary. Yet K. cannot cross it himself, as he futilely tugs at the handle of the door, “which the girls, as he could tell from the resistance, were hanging on to from outside” (162). Instead, he must take the exit to the Law Court offices. What is hardly a boundary for the girls is all too solid for him.

In the above passage, the door becomes a very tangible boundary for K., even though the girls seem to be able to penetrate it with ease. K.’s case will be examined in more depth, but even in this situation, the role of the door is difficult to completely understand. In The Trial, K. finds himself in situations where the distinction between one side of the door and the other becomes very hazy. Without this distinction, K. can neither enter nor exit. The door will cease to function as a gateway and instead will trap K, as the painter’s door does. Unable to exit, he instead takes the route through the Law Offices, ending up nonetheless back where he began. Through doors, K. embarks on a forward progression to nowhere, where both sides of the door may indeed be the same.

The opening scene presents K. with seemingly total freedom. After the warder Willem tells K. to stay put in his room, he considers that “If he were to open the door of the next room or even the door leading to the hall, perhaps the two of them would not dare to hinder him” (7). He soon finds out from the inspector that he is free to go about his business and can still lead his regular life. His freedom to exit his room is useless, however, because he will remain in the same “space” as he is in from the beginning of the novel, and he will not escape it, except possibly through death. Leaving through the doorway of his room will make no difference. His situation, however, will become more clear, as Kafka develops it throughout the novel.

[Very clear, or so I thought at the time. Look at all the stuff I’m about to quote below.]

A certain article which I won’t mention reminded me that I should update my reader’s guide to reader’s guides to Finnegans Wake, since there are a lot of people out there who’d like to read the thing but don’t have the opportunity to take a class in it and don’t know quite where to begin. So I am updating my list of guides to the Wake and sorting it into a few categories.

Most of these books, especially those in the first two sections, are extremely approachable and written in friendly, affable language, certainly moreso than the average monograph. Since Finnegans Wake doesn’t exactly pull in huge amounts of fans, there’s not much exclusionary rhetoric to keep out dilettantes.

Getting Familiar (Easy Peasy Lemon Squeezy)

The Books at the Wake, James S. Atherton.

Ultimately, I think this may be the best place to start, and Atherton’s excellent book was recently reissued in reasonably inexpensive paperback. Finnegans Wake is about the history of the world and the history of every bit of writing in it, and those two things are made to be one. But the Wake does favor certain writers by referencing them very frequently: not just Vico, who provided the historical structure that supposedly partly guides the book’s organization, but Jonathan Swift, Lewis Carroll, Blake, etc. These give very key pointers to some of the things Joyce is driving at. Atherton goes author by author, which conveniently gives an overview of the continuities of the book (one of the more difficult things to grasp on encountering it) while not being beholden to one particular interpretation of it.

Joyce-again’s Wake, Bernard Benstock.

A more thorough and comprehensive overview than Atherton, but also more partial. It is invaluable for the structural outline Benstock gives, which is useful in carving up the monolithic chapters of the Wake into more manageable chunks. It also contains a fantastic analysis of the very important but elusive Prankquean fable located on pages 21-23 of the Wake. The rest of the book both summarizes previous scholarship and elaborates on it in a rather freewheeling fashion. There’s plenty of good stuff, but Benstock sometimes is too exclusive about his readings, and I read them with more salt than I did Hart or Atherton. On Issy, the topic I researched, I disagree with him. A very good introduction, but also one that requires more skepticism.

The Art of James Joyce, A. Walton Litz.

An excellent and short (100 pages) book on Joyce’s working methods on Ulysses and the Wake and how they could possibly feed into the structure and meaning of the works themselves. Litz is admirably humble and cautious about drawing any conclusions, but the emphasis on the construction work makes the whole book seem more approachable and at least begins to give some explanation as to why the Wake is written the way that it is. As Litz says, this doesn’t necessarily say anything about the work itself, but one path into the book is through the process of construction, and at least as Litz presents it, it’s a very engaging one.

Further Immersion

The Sigla of Finnegans Wake, Roland McHugh.

McHugh is one of the most intense Wake scholars, and in The Finnegans Wake Experience he describes moving to Ireland to better understand the book. This slim volume describes, with much reference to Joyce’s notebooks, how the many personages of the book combine into sigla, a dozen or so symbols around which Joyce constructed the book. (For example, HCE in all his various forms is a wicket-shaped “M”, and ALP in hers is a triangle.) Joyce’s sigla changed as he wrote the book, and there’s room for interpretation, but McHugh, like no other analyst, gives the impression of truly grasping the whole damn thing, even as it streams between his fingers. Only my inexpert opinion, but McHugh seemed to be most in tune with Finnegans Wake.

Structure and Motif in Finnegans Wake, Clive Hart.

As the title suggests, Hart’s book contrasts with McHugh’s in tracing linguistic, spatial, temporal, and referential structure through the book rather than focusing on character archetypes or narrative. As such, Hart attempts to describe the macro-structure of the Wake with a minimum of interpretation–which invariably turns out to be quite a lot. Hart is in a lot of contentious territory, but his knowledge is solid and his pace careful. I think of Hart’s book as consciously open-ended: even where I find his interpretations uncertain, they are always provocative and spur even more future questions. This quality, however, makes the book more daunting to a newcomer, who will have less context for the majestic castles in the air that Hart depicts.

A Guide Through Finnegans Wake, Edmund Epstein.

Epstein was my teacher and guide through the Wake, so I am biased. Epstein provides a very structured and very detailed walk through the Wake page through page. He takes an different approach to the book from McHugh and Hart, preferring to focus on the fundamentally human drama at the heart of it, and so he ignores the sigla and treats the man-woman dyad HCE and ALP and their brethren as corporeal, albeit manifold, human beings. In this he is closer to Joseph Campbell (yes, that one) and Henry Morton Robinson, who wrote possibly the first book-length treatment of the Wake with A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake in the 1940s, but Epstein has the benefit of 60 years more research and perspective, and so Campbell and Robinson’s many mistaken guesses are not a problem here. Epstein points out tons of obscure allusions as well, and he is especially good on music and some of the pure wordplay. (I believe he conducted Gilbert and Sullivan at one point or other.) The book is contentious: Epstein has a very definite view of the book’s layout and mechanism, and I believe there is far more ambiguity in it than he does. Grain of salt, etc.

A Reader’s Guide to Finnegans Wake, William York Tindall.

Tindall was an extremely bright and knowledgeable Wake scholar, but I have to rate this as one of the weaker guides. Like Blamires’ Bloomsday Book, it explicates the Wake page by page. Unfortunately, what’s left out is far greater than what remains, and Tindall often makes controversial interpretations without appearing to do so. It’s less of a problem in Blamires because the narrative of Ulysses is reasonably uncontroversial, but since narrative in Finnegans Wake emerges from linguistic confusion and contradiction, Tindall’s approach makes the Wake appear smaller than it is. Provocative and worthwhile, but also worth avoiding until you know enough to spot some of his assumptions.

Specialization and Esoterica (Difficult Difficult Lemon Difficult)

Annotations to Finnegans Wake, Roland McHugh.

Absolutely indispensible for serious reading, but insanely frustrating to a newcomer. For those who haven’t seen it, this is an extensive gloss that maps page-by-page on to the original text with extremely concise, sometimes cryptic notes. (You really have to see it to get the effect.) On first glance the Annotations are just as obscure as the Wake itself, but once I started catching recurrences of certain allusions, it becomes impressive how they match up with particular subjects and characters in the Wake. (For example, Jonathan Swift and Lewis Carroll references occur absurdly often in any section associated with the daughter Issy.) You will want this after having a working grasp of the general shape of the book, but before that it will merely cause nightmares.

Third Census of Finnegans Wake, Adaline Glasheen.

Glasheen started reading the Wake while tending to a newborn and needing something to occupy moments during and in between feedings. Evidently possessed of awesome powers of concentration, she also seems to have inexhaustible enthusiasm. Her book is nothing more and nothing less than a catalogue of all the proper names in the Wake that Glasheen could identify. (It also includes another structural summary with, as is to be expected, some contentious interpretations. I give the edge to Benstock’s summary, though both are very useful.) Glasheen’s list of references is exhausting, if not exhaustive, and effectively serves as an alternate organizational tool for digesting the Wake. It poses thousands of questions along the lines of, “Why did Joyce connect person X with person Y?” Glasheen is also completely unaffected, as indicated by entries like “I don’t know who this is.”

Joyce’s Book of the Dark, John Bishop.

An extremely daunting book. While schooled in the above traditions of Wake scholarship, Bishop goes in another direction entirely, focusing on Joyce’s linguistic methods as theme, particularly as they relate to sleep, the body, and the five senses. Bishop is fond of making extremely short citations and combining them from all over the Wake in close succession, which emphasizes Joyce’s sea of language while downplaying any potential linear continuity. Bishop also analyzes two key mythologies that influenced the Wake, the Egyptian Book of the Dead and Vico’s New Science, but his interpretations are highly heterodox. Consequently, Bishop has the effect of making Finnegans Wake seem even weirder than the other books make it out to be. The book is one of the most learned studies around and takes the Wake in unique interpretive directions, but it may leave you, as it implies, in the dark.

Finding a Replacement for the Soul, Brett Bourbon.

While this book is not exclusively concerned with the Wake, it invokes Finnegans Wake as a central example for Bourbon’s non-propositional view of fiction. Bourbon, I believe, was a student of Bishop and locates Bishop’s nighttime uncertainty in the processes of language itself, taking Bishop’s argument even farther. Not an exegesis of Finnegans Wake, but a reflection on what the Wake says (or shows) about readers and reading.

From Leiter’s blog, Michael Rosen (who wrote the excellent On Voluntary Servitude, a book I would write about if it weren’t so dense that it’d require a huge amount of time to treat it) talks about academic strategies:

Ephraim Kishon has a story called “Jewish Poker”. Jewish poker is played without cards so all you can do is bluff – and you have to bluff high. I think that this is the secret of Derridean post-modernism as currently practised in U.S. humanities departments: in the end, it’s all competitive hyperbole – who can be more radical?

Someone starts off with a huge unsupported generalization. For example, they write a book saying that the whole of Western thought is under the hegemony (good word) of (say) “logocentrism”, that its genealogy has to be exposed and deconstructed to reveal the Other that it “covers over and disavows”.

That’s a high bid, but you can top that. Why not write a review saying that this is to give “the Other” a “hegemonic status”, that this too needs to be deconstructed and given a genealogy? Say that the re-valuation of values hasn’t been radical enough, that “the Nietzschean trans-valuation is far from being complete: in its second stage, at the threshold of which we find ourselves today, it will necessitate a de-hierarchization of the already inverted values, so that alterity, too, would lose its newly acquired transcendental status, just as sameness and identity did in twentieth-century thought.”

Of course, tone and style matter. Although you’ve left banalities like “sameness and identity” (and hence, presumably, essence, cause and logical inference) far behind, don’t hesitate to use terms like “necessitate” for the ideas you are advocating, or (although you don’t believe in such fetishes as truth in interpretation) to describe others’ interpretations as “deeply flawed”. To think that once you’ve toppled the idols of objectivity you can’t write as if they were still standing is a sign of hopeless logocentrism.

It’s good too to write as if your native language isn’t English, or that, at least, your English has been saturated by what you’ve absorbed in your many years on the *rive gauche*. A nice Derridean-Althusserian touch here (see Judith Butler, *passim*) is the spurious use of the term “precisely” when you make an especially vague assertion (“The promise of deconstruction lies, precisely, in its ability to inspire this post-metaphysical thrust ‘beyond the same and the other.’”) Introducing your sentences with pompous phrases like “Let us note that …” may not add anything of substance to them but it does convey the impression that you are addressing your audience from a position of authority (a podium at the École Normale?). Above all, the secret is to convince people that you are further up the mountain than everyone else and looking down on them. Writing in this condescending way won’t make you popular, no doubt, but what the hell – oderint dum metuant!

Where will it all end? Presumably, this too can be out-bid – perhaps someone else will come along and offer a genealogy of deconstruction or a deconstruction of genealogy. There doesn’t seem to be any limit to how many iterations the transvaluation of valuations can go through. Yet there must – surely – come a point where the whole thing vanishes up its own …

But what to do until that happy day? Certainly, it is heart-breaking for those of us who would like Continental philosophy to be taken more seriously, but how do you argue with people for whom “reason” and “argument” (like “sameness” and “identity”) are simply terms in a “hegemonic discourse” they have left behind? And, if they can shrug off the Sokal hoax and take Alain Badiou seriously, they are obviously past being laughed back into sanity by a sense of the absurd. So I think that all the rest of us can do is to keep out of their way and leave them to patronize one another to their hearts’ content.

Rosen and Leiter edited the Oxford Handbook of Continental Philosophy, and seem to be part of a vague movement afoot among Anglo philosophers to write about Continental theorists in comparatively clear and methodical ways. I have a fair bit of sympathy with this movement. One of the ongoing debates, though, is which of the theorists are irredeemable. Here’s how the categories seem to be shaking out, from my perspective. (I could be wrong about any of these; this is just a general impression and not reflective of the views of any single person.)

Solid: Herder, Hegel, Marx, Peirce, Dilthey, Nietzsche, Husserl, Adorno, Merleau-Ponty, Sartre, Habermas

Sketchy: Heidegger, Gadamer, Foucault, Kuhn, Deleuze

Fraudulent: Derrida, Levinas, Althusser, Badiou, Zizek

Given this arrangement, I’m surprised there hasn’t been more attention paid to Vico, Cassirer, Ricoeur, and Apel, but perhaps in time, just as Herder seems just now to be having a renaissance.

I’ll have my own say on Derrida and phenomenology shortly….

© 2025 Waggish

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑