Coarsely abusive sexual language is an early iambic tradition.

Daniel Garrison

Besides being Augustus’s favored poet and composing immaculate and subtle Odes, Horace wrote some rougher-hewn pieces in his series of Epodes (30 BC). The most notorious are the eighth and the twelfth, which are both obscene, misogynistic brushoffs to an older female lover. (In the twelfth, she at least gets in a bit of a riposte at the end.) David Mankin summarizes the eighth as “obscene abuse of a randy old hag” and the twelfth as “further abuse of the old hag.”

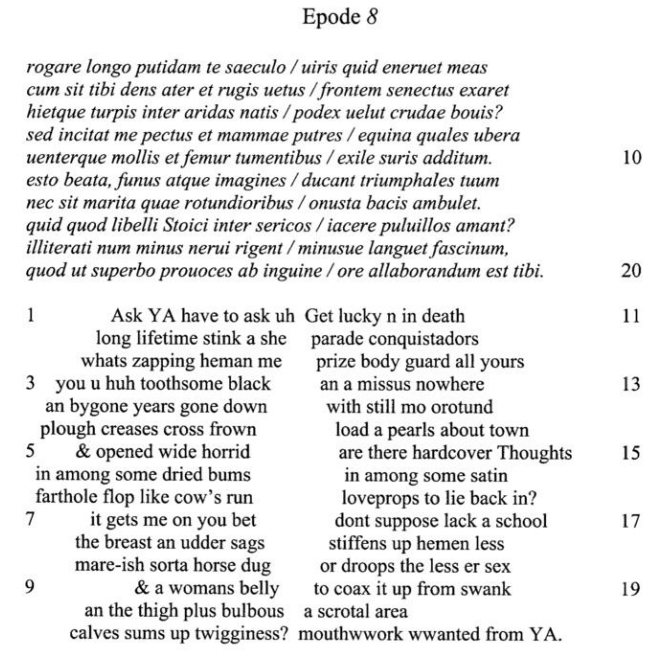

Here’s Epode 8 in Niall Rudd’s Loeb translation from 2004, which I take to be a reasonably close paraphrase:

AN OVER-DEMANDING LADY (Niall Rudd)

To think that you, who have rotted away with the long passage of time, should ask what unstrings my virility, when your teeth are black, and extreme decrepitude ploughs furrows on your forehead, and your disgusting anus gapes between your shrivelled buttocks like that of a cow with diarrhea! I suppose I am excited by your bosom with its withered breasts like the udders of a mare, your flabby belly, and your scrawny thighs perched on top of your swollen ankles! Be as rich as you like. May the masks of triumphal ancestors escort your cortege! Let no wife be weighed down with fatter pearls as she walks proudly by! What of the fact that slim Stoic volumes nestle on your cushions of Chinese silk? Does that make my organ (which can’t read) any stiffer, or my phallic charm less limp? To call it forth from my proud crotch you must go to work with your mouth.

Horace seems to be trying to outdo Catullus, but some of it reads like it comes out of a Shakespeare Dark Lady sonnet. The progenitor of this abusive tradition is the mysterious 6th century BC Greek poet Archilochus, who was promoted by Guy Davenport’s translation in 1964 (also see his introduction to Archilochus from 7 Greeks).

Because of Horace’s high profile, these epodes have necessitated being brushed under the rug up until a recent renaissance. In the 1960s, Eduard Fraenkel called them “repulsive,” while Steele Commager just ignored them altogether. The Latin students edition of 1896 omits them rather conspicuously (they’re numbered, after all), which presumably sent more than a few students to the library to locate the missing poems.

Translators, too, historically excluded the problem poems (8 and 12, but also the far less obscene but explicitly gay 11). After Henry Rider omitted them in his 1638 translation of the complete works, the first person to tackle them was Christopher Smart in 1756. (Also available on the web here.) Smart smooths out the obscenity rather cleverly, but still gets the vitriol:

UPON A WANTON OLD WOMAN. (Christopher Smart)

Can you, grown rank with lengthened age, ask what unnerves my vigor? When your teeth are black, and old age withers your brow with wrinkles: and your back sinks between your staring hip-bones, like that of an unhealthy cow. But, forsooth! your breast and your fallen chest, full well resembling a broken-backed horse, provoke me; and a body flabby, and feeble knees supported by swollen legs. May you be happy: and may triumphal statues adorn your funeral procession; and may no matron appear in public abounding with richer pearls. What follows, because the Stoic treatises sometimes love to be on silken pillows? Are unlearned constitutions the less robust? Or are their limbs less stout? But for you to raise an appetite, in a stomach that is nice, it is necessary that you exert every art of language.

(Fascinatingly, in Epode 11, Smart obscures the gender of the speaker’s male lover Lyciscus, while still leaving in the confession of attraction to both sexes.)

Philip Francis (1746) and Bulwer Lytton (1870) also omit the problem poems from their translations.

In his 1901 Latin edition, C.E. Bennett includes them but does not summarize or give any commentary, beyond the statement “The brutal coarseness of this epode leads to omission of an outline of its contents,” though by this point the gay content of 11 poses no problem. He did not translate 8 or 12 for his 1914 Loeb Library edition either, which relegates the Latin versions to an appendix after the other epodes.

In fact, I can’t find a single English translation other than Smart’s prior to 1960, when two appeared, by Joseph P. Clancy and W.G. Shepherd. Neither seems to pull any punches, though Shepherd goes more over the top with flowery language and a Beat-esque poser:

ROGARE LONGO (W.G. Shepherd)

That you, rotten, should ask what it is

that emasculates me, when you’ve

just one black tooth and decrepit age

ploughs up your forehead with wrinkles,

when a diarrhoeic cow’s hole gapes

between your dehydrated buttocks!

What rouses me is your putrid bosom,

your breasts like the teats of a mare,

the flaccid belly and skinny thighs

that top your grossly swollen shanks.

Be bless’d, and may triumphant lovers’

likenesses attend your corpse.

May no wife perlustrate laden

with fatter, rounder pearls than yours.

What though Stoic pamphlets like

to lie between silken pillows?

Illiterate sinews stiffen,

and hamptons droop, no less for that.

(Though if you hope to rouse up mine,

your mouth is faced with no mean task.)

Comparing to Smart’s translation reveals that Smart was quite ingenious with his adjustments. Shepherd also uses a wince-inducing racial epithet in Epode 12, which I will leave to others to comment on. (The American Clancy, in contrast to the British Shepherd, avoids any mention of race at all.) Notably, both are only coy when it comes to the male member (“sinew,” “rod,” Cockney rhyming slang “hampton”), though this is not the case with either translator in Epode 12.

More recent translations follow the same line but make the language a bit plainer. David West’s version (1997) is quite forthright, less self-conscious about the shocking content.

ROGARE LONGO (David West)

You dare to ask me, you decrepit, stinking slut,

what makes me impotent?

And you with blackened teeth, and so advanced

in age that wrinkles plough your forehead,

your raw and filthy arsehole gaping like a cow’s

between your wizened buttocks.

It’s your slack breasts that rouse me (I have seen

much better udders on a mare)

your flabby paunch and scrawny thighs

stuck on your swollen ankles.May you be blessed with wealth! May effigies

of triumphators march you to the grave,

and may no other wife go on parade

weighed down with fatter pearls!But why do Stoic tracts so love to lie

on your silk cushions?

They won’t cause big erections or delay the droop–

you know that penises can’t read.

If that is what you want from my fastidious groin,

your mouth has got some work to do.

Finally, there is classicist John Henderson’s translation. Henderson is noted for a punning deconstructionist critical style (for which he has been taken to task), and he has written a couple essays on Epode 8, though he is clearly wrong to say (a) that all pre-1980 translations were Bowdlerized and (b) that prior to that the two poems were excluded from virtually all Latin editions with commentary.

Ironically, by adopting a declasse anti-authoritarian patois closer to Shepherd than West, Henderson seems to be trying to recapture the original’s shock value by appealing to shocking standards of a past American era: the artful and self-conscious provocations of Shepherd, reveling in obscenity-as-rebellion rather than obscenity-as-ridicule. It’s a strange and anachronistic brew. I suspect that the blase, imperious ridicule of Rudd and West is closer to the original.