(I recently wrote an overview of Krasznahorkai for The Quarterly Conversation, which may help give some context to the themes here.)

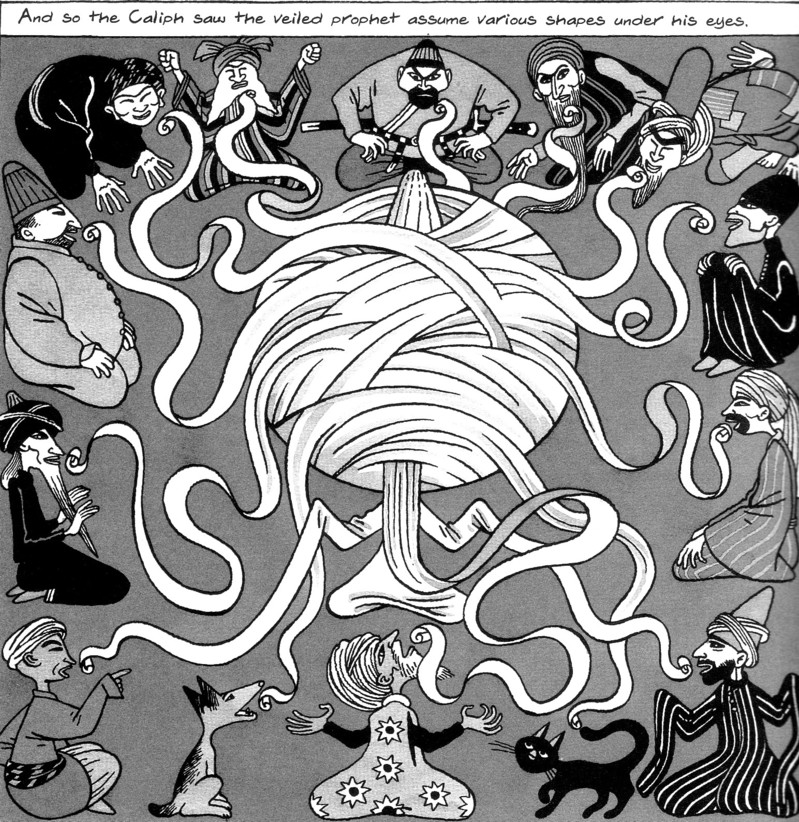

Animalinside, a short work which is published as part of the Cahiers series on writing and translation, is a formal experiment for Krasznahorkai. Krasznahorkai wrote a text to accompany a drawing by Max Neumann, and Neumann drew over a dozen more in response, and Krasznahorkai wrote a short text for each one. There’s an obvious unity to it all: the pictures all feature the (usually) black silhouette of some sort of feral animal poised to jump, and the texts are all about some sort of beast or beasts, usually written in the first person singular or plural. (Notably, the first text is in the third person and quotes the beast.)

The interaction of images and text is not new for Krasznahorkai, as he collaborated with Bela Tarr on at least four films, including two based on his novels. Those last two films diverge significantly from their source texts, and Tarr has said that modifications were made throughout the filming. So here again, despite appearances, I tried not to make too literal a tie between the images and the texts. The affiliation feels more thematic than literal. The beast’s silhouette is usually black, but occasionally white or gray. These shifts make themselves felt in the beast’s attitudes in the text for each picture. The color as well as the use of space is treated metaphysically. Neumann’s subsequent drawings after the first seem to bring out themes already present in the first text, which Krasznahorkai then elaborates on. Whether they form an actual narrative is ambiguous, but they certainly form a whole.

The beast is angry, but helpless. The beast rants about how he is beyond any constraint that can be put on him by thought or concept. He is unique and beyond comparison: “It is impossible to confuse me with anyone else.” He is within you, caged in one picture, but he is struggling to break free. And so another of Krasznahorkai’s conceptual contradictions emerges: the beast that is at once free beyond everything and yet trapped.

The beast is beyond imagination, beyond containment, beyond conception…but not beyond language. At first, his rantings about chaos and the destruction of anything and everything call to mind The Prince, from The Melancholy of Resistance. But The Prince himself spoke gibberish which was then translated by a Factotum. (In the movie version, however, he speaks Slovak! Thanks to Gwenyth Jones for pointing this out to me.) Our beast here speaks for himself, and in doing so he reveals a weak spot. When the beast faces infinity in the picture accompanying the ninth text, he must rail against it too:

I hate all that is infinite, there burns within me an unspeakable hatred towards the infinite…the infinite is a deception, the infinite is a deception in space, the infinite is a deception in measuring, and every aspiration to the infinite is a trap, but the kind of trap that has to be walked into again and again by him who, just like myself, is searching for the end of a direction, for I have no other aspirations.

Is the beast railing at the infinite itself, the inadequacy of the concept of the infinite, or the representation of the infinite (as in this picture)? I’m not sure. This tension is the same one that occurred in Krasznahorkai’s earlier From the North by Hill, from the South by Lake, from the West by Roads, from the East by River, which contained a book by a mad Frenchman ranting against Cantor’s mathematical conception of infinity. Perhaps the idea is that the conception traps us while simultaneously facing us with its inadequacy, and this is unbearable because, as with the ideas of mortality and immortality, neither side is a conceivable solution.

Because the text is more rarefied and abstract than Kraznahorkai’s other work, it seems to resemble Beckett at times. But Beckett never portrayed such a vicious antagonism. His personae always collapse into themselves. Even their assertions of antagonism are hopeful but futile gestures against solipsistic nightmares. That is not the case in Krasznahorkai. I do not think it ever is. His characters and voices are always struggling within a larger cosmos of forces and others.

Anyone who has been reading me knows that I think Krasznahorkai is one of the greatest living writers, and as I’ve read more, his work hooks together in an increasingly revealing way. I know that a translation of Satantango is due out next year, and hope that more is on the way.

Update: Daniel Medin points me to an article by the translator of Animalinside, Ottilie Mulzet. She analyzes the work in the context of the apocalyptic imagery of the Bible, an approach similar to that which I saw in The Melancholy of Resistance. The key line in the essay for me is “The form that this End would take remains unvoiced, perhaps even too ghastly for articulation. [emphasis mine]” Also notable is this instruction that Krasznahorkai gave Mulzet: