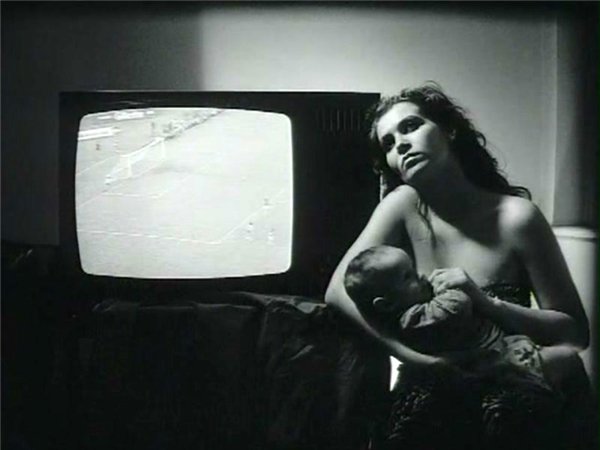

Janice Lee is an American writer, artist, editor, programmer, and generally well-rounded intellectual. We discussed her recent book Damnation and its influences from the work of Hungarian director Bela Tarr and writer Laszlo Krasznahorkai (responsible for the film Damnation), the difficulties of being an “American” writer and what that even means, the grim brilliance of Hungarian culture, and the end of the world. I recommend checking out Damnation and her earlier works Daughter and KEROTAKIS, available at her site JaniceL.com. She is also the executive editor of Entropy Magazine. Many thanks to her for her time and patience in engaging with me.

DA: I was happy to see you mention Pamela Zoline’s science-fiction stories in your best of the year. I read “The Heat Death of the Universe” as a teen and thought it was quite remarkable, and quoted it in an art essay I wrote last year, Archimedes’ Mindscrew. Zoline’s story is, I think, very directly apocalyptic, which connects her to Tarr and Krasznahorkai’s work. Krasznahorkai has spoken of his “personal relationship with the apocalypse,” and Tarr’s landscapes often look like the black and white residue of some post-nuclear blast. “Even if this is the apocalypse, if you stay indoors and mind your own business, the angels and demons will leave you alone” (Damnation). What I get from all of these artists is a negating of the seeming scale of things: apocalypse isn’t a definable event or a point in time, but something baked into the order of things. (Which is why, I presume, entropy has held such an appeal to many apocalyptic writers.) Krasznahorkai says that the apocalypse has already happened. So what is apocalypse for you?

JL: “We are living in the apocalypse. The first moment of life was the first moment of the apocalypse and death. Please, don’t fear the apocalypse.” This quote by Krasznahorkai is maybe the one that resonates with me the most, this idea that we are already and have always been living in the apocalypse. The apocalypse, for me, is more of an anticipatory state. In another interview Krasznahorkai talks about birth as a journey towards failure, this inevitable journey that becomes the life in which we live, bookmarked by these two events in time. But, as we see in Tarr, time carries on without us. Time is the vantage point from which we observe and anticipate. And in one way, the real tragedy is that we must go on whether or not the apocalypse is really coming. That we go on, is the heroic gesture, is the gesture of hope. The apocalypse is about failure, but also about relief and hope. It is about the modification of reality, the ability to see the world from a pair of eyes not just one’s own. It is about disintegration and ruin, yes, but also about empathy and the relationships between human beings. It is about the acceptance of uncertainty over clarity and an abandonment into the beauty of reality. It is about the plateau, the daily struggle, not the end.

DA: For all the talk about the “death of the subject,” it seems like people still return to interpersonal relationships, even familial relationships, as a place to ground themselves. Even if we are neurologically predisposed to find meaning there, we do not seem to want to let go of family or friendship in the same way that we let go of God. You titled a book Daughter, where you call a daughter “the excavator of dead gods,” and you dealt with Frankenstein, the synthetic child, in KEROTAKIS. I’ve been amazed at the sense of stability and certainty (comparatively, at least) given to me by my child. Campanella and Plato wanted to emancipate humanity from the idea of the family (nuclear or extended oikos), but the idea has never gotten much traction outside of cults. For me it’s due to two nigh-unassailable factors: the ability of creation within the family, and the reification of blood ties (real or virtual). The family is the ultimate self-propagating cult. You’ve written, movingly, about the death of a parent; what does that mean to you relative to the apocalypse, relative to time?

JL: The death of parent both changes nothing and everything. What happens during grieving, which lasts an entire lifetime, is different at various moments of life. When my mother died, it was sudden. I was sad, yes, but also shocked, and heartbroken in a way that only dealt with the finality of a life, trying to come to grips with an absence that wasn’t felt as a significant presence until the finality of death. Probably what hit home the hardest was when we returned to my parent’s house one evening and my dog proceeded to run around the house looking for something. He went into every room repeatedly, sniffed all of the corners, looking up at me, looked some more. He was looking for her of course, without the ability to understand that she wasn’t coming back, but also with an understanding that something was wrong. The apocalypse is a prolonged state for me, the anticipation of some finality, but this, too, is living. In one moment I remember my mother and realize how much I have become like her. In another, I lament the strange construction of an identity I have created after her death, how the collage of memories I have pieced together into an identity says more about what I need in this moment from her than who she really was as a human being. I think about how we remain constantly and incessantly surrounded by ghosts, and again, these ghosts say more about the present moment in which we find ourselves in than the ghosts themselves. After all, it is us who keeps them here, not them who linger.

DA: Does time go on without us? One modern philosophical theme is the idea of the block universe, the idea that time is a human construct and all moments exist on equal footing with no concept of “now.” I read this as fundamentally similar to Nietzsche’s eternal return, since each moment is a moment that becomes emblazoned eternally. Yet physics seems to indicate profound incomprehensibility at the heart of things, such that even as we try to grasp the universe-without-us, the universe-without-us turns out to be the universe-without-us-with-us.

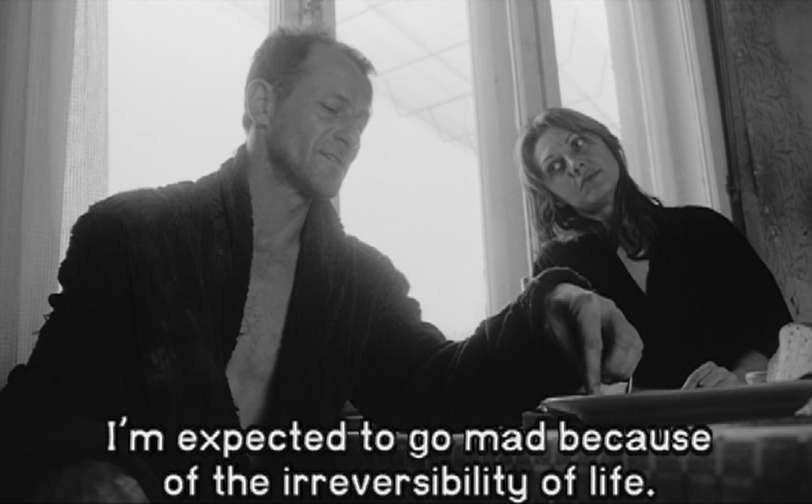

JL: Indeed. There is time, and then is time. What both Krasznahorkai and Tarr really point to is how subjective time is, how eternity isn’t a quantitative measurement, but more of a feeling, an endured and continuous state. Eternity can last 4 seconds, it can last hours. So time becomes something that may or may not exist outside the human world, but at least it is only significant and felt when embodied corporeally.

DA: I recently read British-Chinese novelist Xialu Guo complaining that American “realism” was a limiting ethic. Your work certainly doesn’t embody the sort of conventional writing to which she’s referring, but my reaction was Krasznahorkai’s work certainly feels more real to me than the sort of literal mundanity peddled by people from Franzen to Tao Lin. Looking at the situation in Ferguson, it reminds me more of The Melancholy of Resistance than The Corrections. But then, American literature always seems to have had a legitimacy problem. As Ann Douglas wrote, “Melville’s writing is alive with his outraged conviction that he cannot produce a work significantly better than his culture.” I think that the aspiration to a 19th century European-style realism (like that of early Henry James) is one alternative response to that problem. Is it time to reclaim “realism”, or throw it away?

JL: Realism is always such a tenuous and odd term for me. I mean, much of art has been dealing with this notion right. What is more or less realistic? What more or less embodies or expresses what is real? Once in a writing class a professor compared the work of Samuel Beckett, where real is someone trudging through the mud for countless pages, versus Bertolt Brecht, whose plays point to constructedness of reality itself. Or to look at a photograph of a vase of sunflowers versus a painting by Van Gogh where the deformity and texture and warpedness and colors of the sunflowers enacts a different kind of reality than the photo representation. Krasznahorkai’s work feels real to me in the way that it invokes such familiar qualities of abjectedness and intertia. There is mud, yes, but the humans who insist on moving through the mud, persistent. These kinds of impulses seem to human to me, so real, even if these people are so far from the reality that I live in everyday. Even something about Krasznahorkai’s sentences, the language that seems to constantly overturn itself, these protracted moments where the present gets drawn out in this way but continues to change direction. “Real” makes me think of expression and the dilemma of expression, or the dilemma of representation. So much is inarticulatable. And sometimes the inarticulation becomes the articulation. For example, I’ve been obsessed lately with taking photos of the sky and the sunset in Los Angeles. But these photos can’t capture any of the essence of what I feel in those moments looking up at the sky. That’s an impossibility. But the photo then becomes the articulation of that inarticulatable moment in a way that the evidence acts as a frantic ghost, a wound, a relinquishing of the everything of a single moment into a concentration of something, no matter its density or weight.

DA: America has a long-running streak of Millenialism in its religious populations, but in my own reading I’ve always felt like Eastern Europe has really had the monopoly on doomy apocalyptic literature–and that in contrast, modern secular America is very good at minimizing eschatology and doom (malaise, yes, but not doom). So when reading Damnation through two lenses, first my own American lens and then through my image of Tarr and Krasznahorkai’s European presence, and I felt somewhat dislocated, caught between my preconceptions of American garrulousness and Eastern European austerity. This was one of the reasons I wanted to read your other work, to see how to what extent I would feel one association or the other; what I noticed in those other works was, in fact, that your use of religious and morbid content acted to smooth over the gap between these two divergent conceptions. So aside from asking for your reaction to my own impressions, I’d like to ask whether you feel a particular American component to your work, and to what extent you feel other lineages (whatever they may be) tugging on you?

JL: This is a hard question for me to answer. Mostly, because I’m not sure. I’ve never been to Europe. I can start there. I’ve actually never left North America. Nor do I feel any strong or direct connection to the history or culture of Eastern Europe. Yet, nonetheless, the worlds of Tarr and Krasznahorkai make sense to me, make more sense to me than probably any of the other worlds I’ve encountered in film or literature or art yet, and I’m still wondering why that is. I was very pleasantly surprised, when, taking this silly little online quiz, to find that my test results deemed Hungary as the country of my internal citizenship. So maybe there is something there. But something more to do with the bleakness, the worldview, the hope, the empathy, etc. rather than the specific history or culture. Whether I feel a particular American component to my work, I can only answer that with the above, and an added piece of information that, well, yes, I’ve lived in America my entire life and will probably die here. Yet, I’m still not sure of this relationship between a writer’s country and the art that is produced.

DA: Hungary, or more generally the “Alpine-Carpathian zone” (in Paul Magocsi’s term) has been a touchstone for me as well. The area produced a huge number of influential scientists and mathematicians in the 20th century as well, in addition to its great artists, yet I’d be hard-pressed to make a generalization about it other than a generally dour, skeptical, yet curious worldview. When I was in Slovakia two years ago, I felt a bit more at ease with the willingness of people to criticize and express themselves unselfconsciously, as though the freedom to speak one’s thoughts would be welcomed without it being taken as a personal affront. Even something as simple as saying, “Have you read X?” to a stranger and hearing “Yes, I didn’t like X” was refreshing. But as Douglas says of Melville, the inability to come to grips with America is probably one of the signposts of being a real American writer. America simply does not seem to produce national figures like Goethe, Pushkin, Shakespeare, or Soseki. T.S. Eliot had to go to England to become a national figure there!

JL: I’m becoming more and more convinced that I really need to visit Hungary ASAP, to really be in the physical space and investigate what it is about that place that draws me so close and which I somehow, from a great distance, empathize with so closely.

DA: You work as a programmer, as have I. There was a time, centuries ago, when the sciences and the humanities were not so differentiated, long before C. P. Snow made his “two cultures” argument. For me this split is something I live, because writers of all stripes are so different from technically-minded people, and each points out the deficiencies in the position of the other (and how I possess both sets of deficiencies.) More than anything else, the public image of technology, in the eyes of writers, bears no resemblance to technology as I relate to it and as most techies I know relate to it. What is often called dehumanizing or mechanistic I see as blessedly regular and beautiful, a source of beauty purer than that in all but the greatest works of art. This was why I was drawn to Robert Musil, for trying to reconcile the two, and Krasznahorkai touches on this at length in his references to the mathematics of tuning and Cantor’s infinity. This too seems to be common to the region; Ferenc Karinthy’s Metropole is one of the most precise books about being lost in language that I know. And it is the fierce organization of sections like “The Machinist” in Damnation that makes me think of programming. Where are the joins for you?

JL: I agree that it seems these kinds of modes of thoughts and roles seem to be getting more and more specialized. But honestly, to me, I’ve never distinguished between these disciplines. I work as web designer, yes, one of my many modes of thought and being. Evident from my first book, KEROTAKIS, I’m also research-obsessed and have a lot of interests, including neuroscience, the occult, alchemy, the paranormal, ufology, biological anthropology, psychology, theology, phenomenology, etc. I just mentioned in another interview that I like to stay away from aesthetic categories that act as constricting forces and rather, see all these disciplines and areas as overlapping wavelengths on a broader spectrum, or different perspectives on the same subject of study, namely, life. I wouldn’t be a writer if I didn’t study science first. I wouldn’t see narrative the way I do if I hadn’t, in some part of my life, been on the track to be a doctor. And I wouldn’t have the relationship with language I do today without the films of Bela Tarr. That is to say, it’s hard for me to separate between these areas, between the sciences and humanities even, at least in my own practice.