By far Bioy Casares’ most famous story, “The Invention of Morel” is still fairly obscure, despite being plugged (and strongly influenced) by his friend Borges, and supposedly being the basis for Last Year at Marienbad. I don’t know that it is the perfect work of genius that Borges claimed it is, but it’s certainly ahead of its time for 1940, and the ideas that fuel it are a grade above what Bioy Casares typically used in his work. Bioy Casares lacked Borges’ intensity and his sheer inventiveness, but in “The Invention of Morel,” he used what he had well.

The nameless narrator is a fugitive who has escaped to a remote, abadoned island that has the stigma of disease over it. He sees himself as an outcast, and the story begins to play out a ultra-Robinson Crusoe scenario, as the narrator’s links to reality appear to be severed in Wittgensteinian fashion. Will he lose his capacity for language? Will he lose his humanity? Yes, but this process is interrupted, then furthered by the sudden appearance on the island of a number of refined sophisticates, including the beautiful Faustina, whom he falls in love with. This despite the fact that none of them will acknowledge his presence. Other strangeness occurs, notably the presence of two moons and two suns in the sky.

It’s impossible to go further without revealing the main conceit, which is held back for over half the story, but there’s a pleasure to be had to it being revealed over the course of the story, so please imagine a tacky little spoiler warning here.

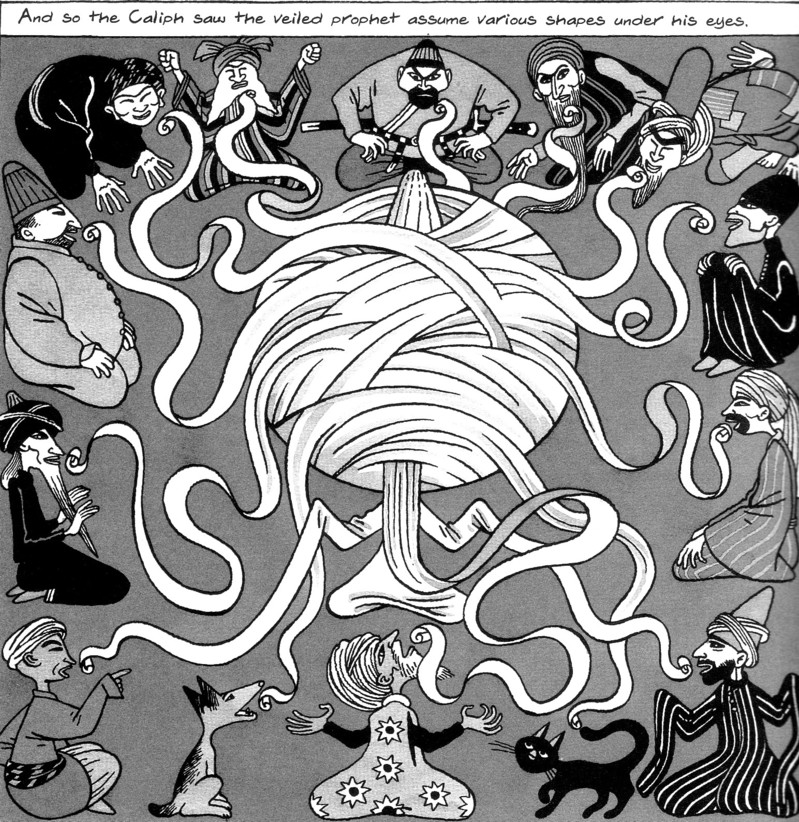

The narrator’s inability to relate to the others seems to be symbolic. He could be dead and existing as a ghost similar to the narrator of Nabokov’s The Eye (my favorite of his works, incidentally). His unspecified crime could have cast him out from the fabric of humanity and left him socially invisible. He could be imagining or recreating life on the island when he is in fact alone. But these are all wrong; the hints of anomie are, ultimately, a blind. The explanation is that he is not seeing people, not quite; what he is seeing is a projection of a recording made of past events, but a projection that has its own reality and is being superimposed on the island (hence the two sun and two moons). The leader of the group, Morel, concocted the invention, which will endlessly replay the week they spent on the island years ago. The downside is that at the time of projection, the force of the superimposed reality is so strong as to draw the life from those recorded and place it in the projected copies. Morel says, “When all the senses are synchronized, the soul emerges,” and he means it literally: the recreation in reality of the past events supplants the current reality of their participants.

Bioy Casares combines two themes in unorthodox fashion. There is the circular time/eternal recurrence theme that so fascinated Borges. In 1941 he wrote:

In times of ascendancy, the conjecture that man’s existence is a constant, unvarying quantity can sadden or irritate us; in times of decline (such as at the present), it holds out the assurance that no ignominy, no calamity, no dictator, can impoverish us.

And Bioy Casares evokes both the horror and the wonder that a week of reasonable existence with only minor troubles should become an eternal prison for its unknowing participants. The second theme is the transmigration of consciousness from the original person to the replica, which then plays out its part endlessly, never knowing that it has done it countless times before, nor that is not the original person–partly because it is. Bioy Casares uses a consciousness thought experiment decades before they came into vogue: if you were to create a copy of a person in an identical context, what would there be to differentiate the copy’s consciousness from the original’s? Since Bioy Casares adopts an emergent view of consciousness in the story (see Morel’s quote above), the answer is that they cannot coexist. It takes the inversion of “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” where the picture and not the man is subject to time, and inverts it again, so that the playback of a recording of events takes on greater reality than the continued existence of the subjects.

The injection of ideas on consciousness is brief but it elevates the story from pure fantasy to the level of, say, Borges “Funes the Memorious.” There, a man remembered everything and was crippled by it; here, people have the identical set of empirical situations played out for them, with no additional memory of it, while the metaphysical conditions change totally. Morel claims his machine creates nothing, only replicates what exists, but Bioy Casares makes it clear that the machine restructures reality. Bioy Casares also implies epiphenomenalism–the idea that internal experience supervenes on material reality without being able to affect it–since under the new conditions of Morel’s machine, the participants are absolutely unable to acknowledge that anything has changed.

The basic concepts here were used in many, many science-fiction novels later on (though not so many beforehand, as far as I know); the story is unique for its alienation from the consciousness that persists on in the projections. In nearly all other stories of shifting metaphysics, the characters still obtain a working knowledge of the problem at hand, which ultimately provides their only satisfaction; here, Bioy Casares sets up a situation in which they cannot. Christopher Priest’s The Affirmation provides the closest echo I can think of, and it too gets around the self-knowledge issue by giving the reader more information than any character has. “The Invention of Morel” plays utterly fair and is more successful in contradicting any conception of what the “consciousness” of its characters could be.