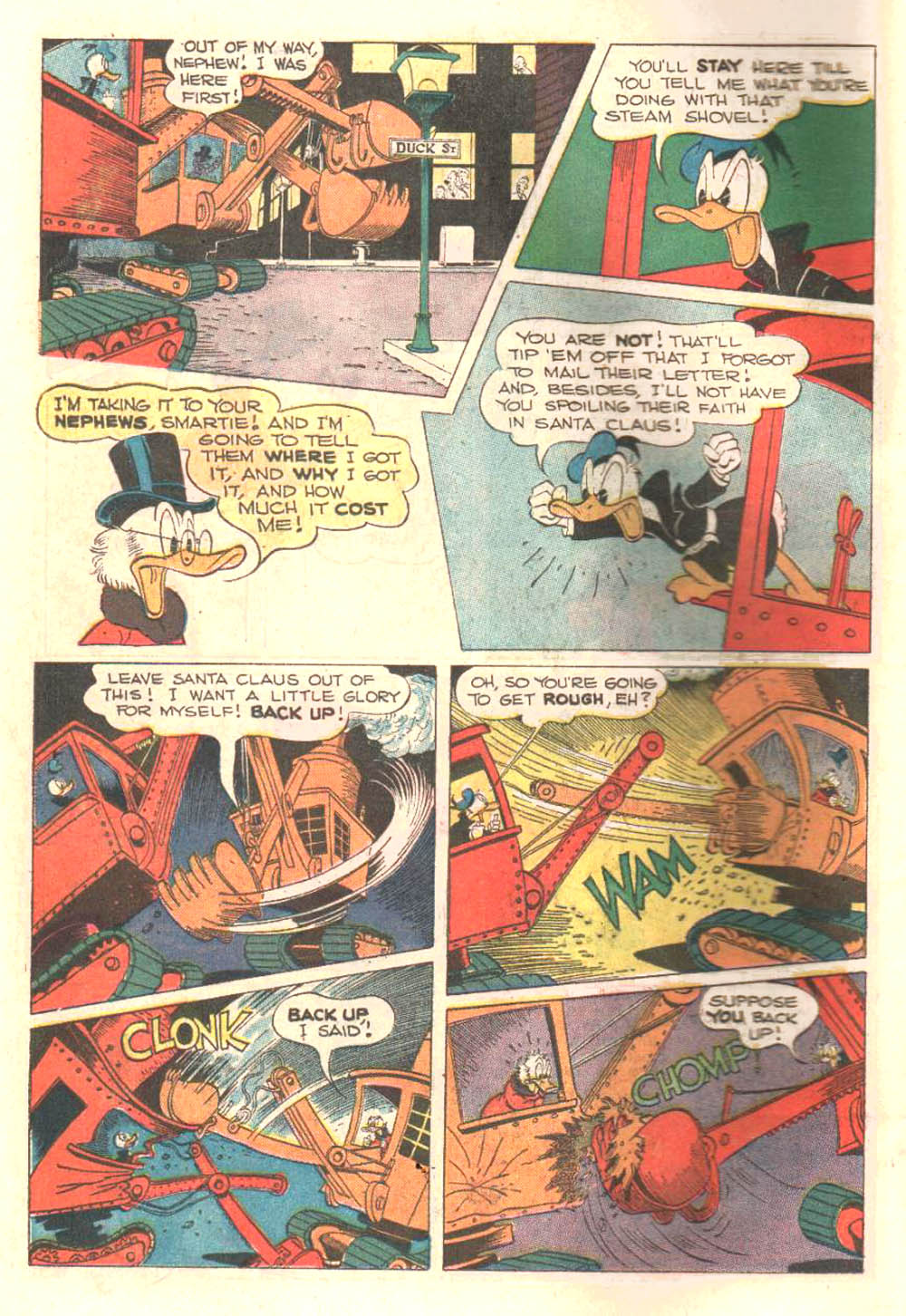

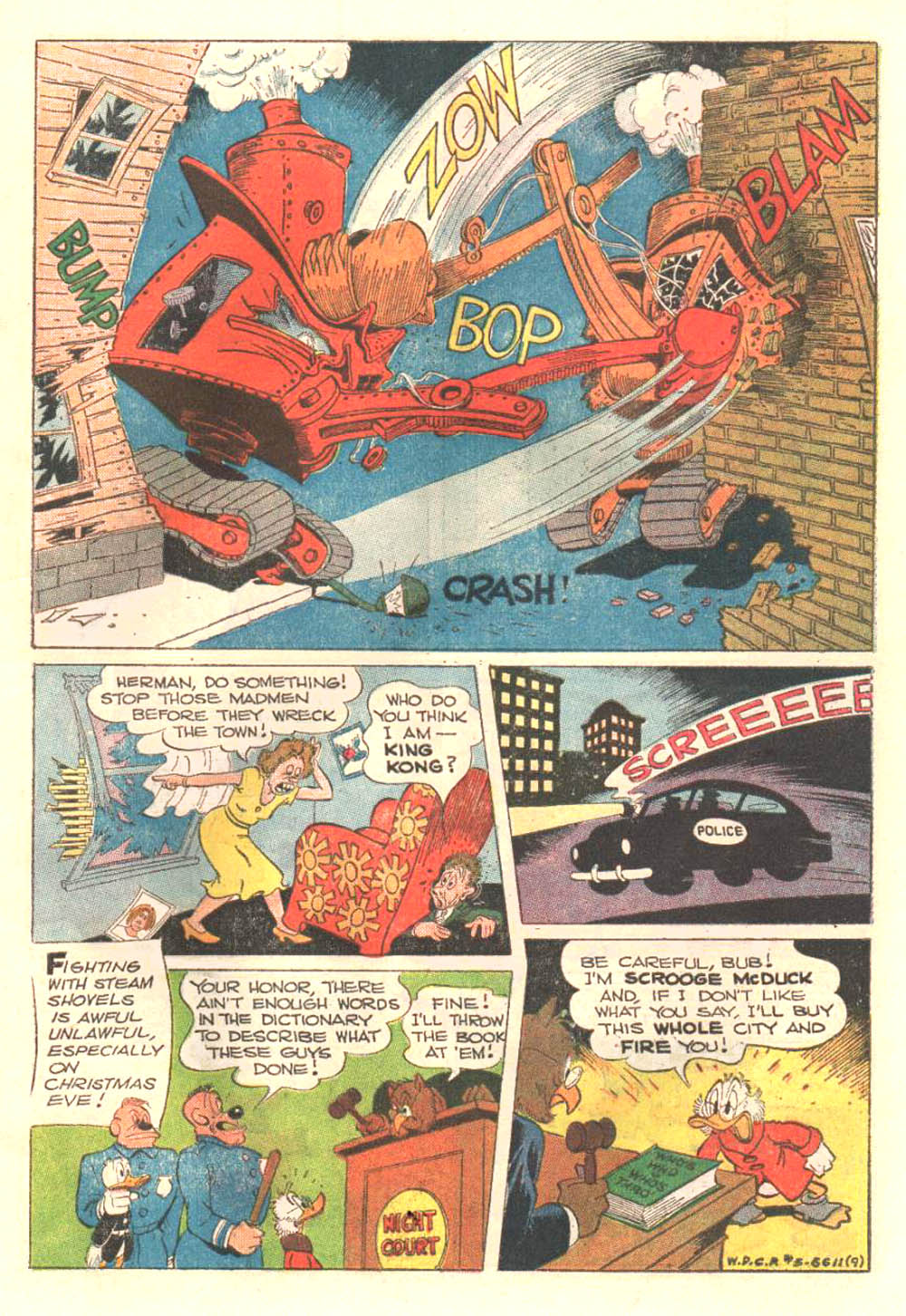

When I was a kid, and I mean a cheerful, oblivious 8-year-old who was gobbling down Donald Duck comics, I couldn’t tell the difference between Carl Barks’s artwork and the rash of those inferior artists who succeeded and co-existed with him. I knew that his writing was better, though Gold Key/Whitman’s endless reprinting of his painful “Riches, Riches Everywhere!” story occasionally put that into question. But out of a sheer lack of visual acuity, I couldn’t see why it was that his drawing was so much more skilled, so much more well-proportioned, so much more careful. There actually was one difference that allowed me to identify Barks, once I figured it out: Barks was the only artist to use pie-cut eyes for all of his characters. Quality of artwork? Mystery to me. I hear these days that Tony Strobl wasn’t such a bad artist compared to those who followed, but at the time I couldn’t even tell.

Then the wave of fans who’d been Barks fans came around, with Another Rainbow and Gladstone doing their best to reprint the choice stuff and find new work of a higher grade, instead of picking randomly and often rather badly. Daan Jippes, William Van Horn, and Don Rosa were the big names. They used pie-cut eyes. They were committed to recreating Barks’s particular vision of Donald Duck, Uncle Scrooge, the nephews, and all the other incidental characters. Since by that point I’d exhausted the collected works of Barks, I gobbled down the new work, which seemed as good as Barks’s stuff. And I liked Rosa the most, because he seemed to buy into the greater mythology of it all; he was the most obsessed with past references, with dense storylines, with establishing new characters in the old continuum. The willingness to work with huge amounts of archival material as gospel and yet go no further (any sort of rewriting, much less “deconstruction”, was strictly verboten) may be summed up best by this Q&A of a Disney animator:

Q: Who’s your favorite Disney character?

A: Love Dewey, hate Huey.

Now I look back and I see it as a breed of fandom much like those in science fiction and mystery circles. Rosa got too caught up in writing sequels to old Barks stories and eventually got lost in his “Life and Times of Scrooge McDuck” project, which is so focused on cramming in offhand references from every Barks story ever written that the characters end up as bizarro-world versions of themselves, carrying out actions without a context. I didn’t care for it at the time and next to “The Son of the Sun” and “Cash Flow,” which are solid, entertaining yarns, “Life and Times” gets bogged down in hero worship and the self-imposed majesty of the project. It is not quite a story; it is closer to Harry Blamires’s Bloomsday Book.

Rosa is unapologetic. In The Comics Journal #183, he said:

Strangely enough people ask, “Aren’t you excited about creating your own characters?” And I say, “No, I want to use Barks’ characters!” That’s the thrill, not creating my own. It’s taking one of his characters and doing something else with it that I love. Because Barks used so many of them only once I can actually use these characters a second time!

I don’t think the basis of fandom is simply one of arrested adolescence; the scenes that you see on the internet, at conventions, and in specialist bookstores are a parallel culture to the more traditional literati, with completely different mores and notions of status. But the urge to so completely inhabit a world delineated by an idolized master creates a ghetto for such work pretty quickly. (Again, there are Joyce “scholars”, and there are Joyce “obsessives.”) There is a similar stigma that surrounds Gustav Janouch’s dubious Conversations with Kafka, which, nonetheless, contains quotes that “If Kafka hadn’t said, you really wish he had.”

I’m not going to pass judgment on Rosa’s approach, but I will say that for a while he succeeded. When I first read the early stories, they might as well have been new Barks stories as far as I was concerned. Maybe this speaks to a lack of discrimination in my prepubescent years; it doesn’t matter, since the new stories weren’t intended for an eye that would be first drawn to Rosa’s more crowded and worked-over art rather than the basics of plot and character. They were aimed at someone who would read them as though they were additions to the master’s oeuvre.