G. Wilson Knight was a mid-century critic probably most known for an infamous little essay on Hamlet he wrote in 1930 called “The Embassy of Death” (collected in The Wheel of Fire). The essay is sort of a troll. He argues that but for Hamlet himself, Denmark is a happy, lively place under the wise, gentle rule of Claudius. But for Hamlet’s mad injection of himself into the proceedings, which destroys most of the characters and the state itself, things would have been fine. Hamlet is the sick, deranged soul who drags down a healthy world.

Now, Wilson Knight has some very keen points to make that go against the standard interpretation, but the essay is written in a gallivanting style that makes it clear that Wilson Knight knows he is being provocative. And so he is going over the top to make Hamlet as bad as possible and make every excuse for Claudius (who did murder the old King, but come on, let’s not dwell on it). You can imagine Wilson Knight barely able to keep a straight face as he goes into hyperbolic rhapsodies over Claudius’s pax Denmark and Hamlet’s malevolent presence:

Claudius, as he appears in the play, is not a criminal. He is—strange as it may seem—a good and gentle king, enmeshed by the chain of causality linking him with his crime. And this chain he might, perhaps, have broken except for Hamlet, and all would have been well. Now, granted the presence of Hamlet—which Claudius at first genuinely desired, persuading him not to return to Wittenberg as he wished—and granted the fact of his original crime which cannot now be altered, Claudius can hardly be blamed for his later actions. They are forced on him. As King, he could scarcely beexpected to do otherwise. Hamlet is a danger to the state, even apart from his knowledge of Claudius’ guilt. He is an inhuman—orsuperhuman—presence, whose consciousness—somewhat like Dostoievsky’s Stavrogin—is centred on death. Like Stavrogin, he is feared by those around him. They are always trying in vain to find out what iswrong with him. They cannot understand him. He is a creature of another world. As King of Denmark he would have been a thousand times more dangerous than Claudius.

I have concentrated on Claudius’ virtues. They are manifest. So are his faults—his original crime, his skill in the less admirable kind of policy, treachery, and intrigue. But I would point clearly that, in the movement of the play, his faults are forced on him, and he is distinguished by creative and wise action, a sense of purpose, benevolence, a faith in himself and those around him, by love of his Queen…In short he is very human. Now these are the very qualities Hamlet lacks. Hamlet is inhuman. He has seen through humanity….

He has seen the truth, not alone of Denmark, but of humanity, of the universe: and the truth is evil. Thus Hamlet is an element of evil in the state of Denmark. The poison of his mental existence spreads outwards among things of flesh and blood, like acid eating into metal.They are helpless before his very inactivity and fall one after the other, like victims of an infectious disease. They are strong with the strengthof health—but the demon of Hamlet’s mind is a stronger thing than they. Futilely they try to get him out of their country; anything to get rid of him, he is not safe. But he goes with a cynical smile, and is no sooner gone than he is back again in their midst, meditating in grave-yards, at home with death. Not till it has slain all, is the demon that grips Hamlet satisfied. And last it slays Hamlet himself.

“The Embassy of Death” (1930)

I really like the essay as a performance, since it does (if you’re not completely alienated by it) make you realize how equally unlikely the contrary and common interpretation is, with Hamlet the good guy and Claudius the fount of evil. But Wilson Knight evidently saw that if he was going to make a critical impact, there was no point in being restrained. He might as well push his own account to the limit, even if it completely broke with plausibility. Outrage trumps reasonableness and moderation.

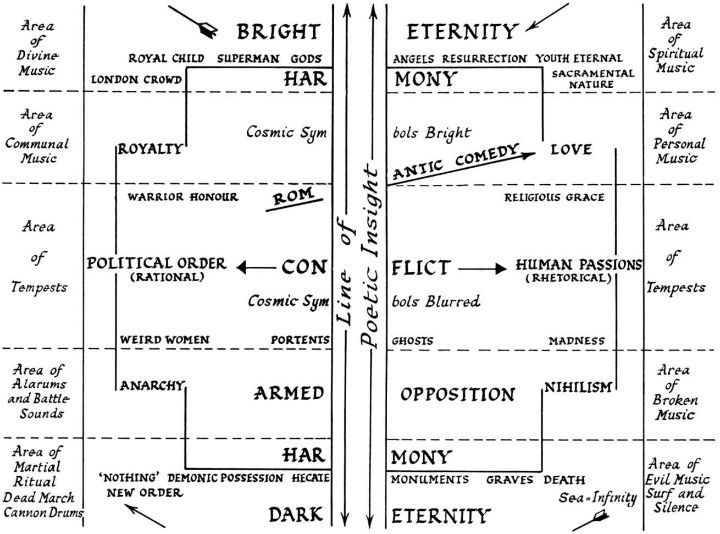

Yet it wasn’t especially a cynical gesture, seemingly more a temperamental one. Years later he published his chart of Shakespeare’s Dramatic Universe. Here it is again:

And the first thing I think on seeing this is, “You would have to be insane to come up with something like this.” Maybe not to come up with it, but to publish it, along with a long explanation of which this quote is representative:

On the right we have personal qualities; on the left, social and political. In the centre is a creative ‘conflict’ (not exactly ‘disorder’) related to the clash of individual and society. This conflict is nevertheless mainly inward and spiritual, and most fully experienced within the protagonist. It next tends, like a cyclone or hurricane, to move down the chart, developing into ‘armed opposition’, with the area columns showing a strong divergence of personal and communal symbolism as the rift widens; and so on to a tragic resolution.

The Shakespearean Tempest

It reminds me a bit of the schemas that Joyce made for Ulysses, except that those were (a) explicitly partial and ex post facto, and (b) by the author for a single work. To come up with something like this for the entirety of Shakespeare’s works is a whole different level, and my next impulse is to start tweaking it and adding to it, shortly before I realize that it would be silly, because this chart is an attempt to turn Shakespeare into his near-antithesis, Dante. And clearly another bizarrely perverse impulse of Wilson Knight’s, as he pretty much says:

But our chart should at least serve to indicate the danger of saddling Shakespeare’s world with any static scheme whatsoever. Only when these various powers are recognized shall we understand the true process of harmonization at work.

And then I think that James Joyce really did achieve as close of a merging of the two as was possible, by taking a million schemas and attempting to superimpose them over one another simultaneously in his last two novels. And Wilson Knight’s choice of anchoring motifs–music and tempests–are pretty good ones.