One of the most frequently discussed motifs in Civil War is how Lucan pays very little respect to the integrity and unity of the human body. Partly this is because a good chunk of the poem consists of bodies being dismembered and desecrated, but it goes much deeper than that. Multiple bodies are assimilated into one. Individual bodies are broken down into pieces. And the individual soldiers, even when they are named, are almost completely anonymous, no more than cells in a larger body.

Roman literature had a tendency toward the gory, even in high-minded verse like the Aeneid, but Lucan is unprecedented in my knowledge for the extremes to which he took the focus on the viscera. I give interesting but overrated theorist Mikhail Bakhtin flak for his distinction between the monovocal epic and the polyvocal novel, because Lucan does with his epic pretty much everything which Bakhtin claims only the novel can do. But this remark of Bakhtin’s, quoted by Shadi Bartsch in her Lucan study Ideology in Cold Blood, is dead accurate:

The grotesque image displays not only the outward but also the inner features of the body: blood, bowels, heart and other organs. The outward and inward features are often merged into one.

Mikhail Bakhtin

The merging, the confusion, the atomization: Lucan has it all. At the end of Book III, he tells of the treatment of the bodies after the battle of Massilia:

Oh, how parents wept

back in the city! Loud laments of mothers on the shore!

Many wives embraced an enemy soldier’s corpse,

mistaking the face defaced by the force of the sea.

Over burning pyres miserable fathers fought

over headless bodies. But Brutus, victor at sea,

conferred on Caesar’s army its first naval glory.Civil War III.783-9

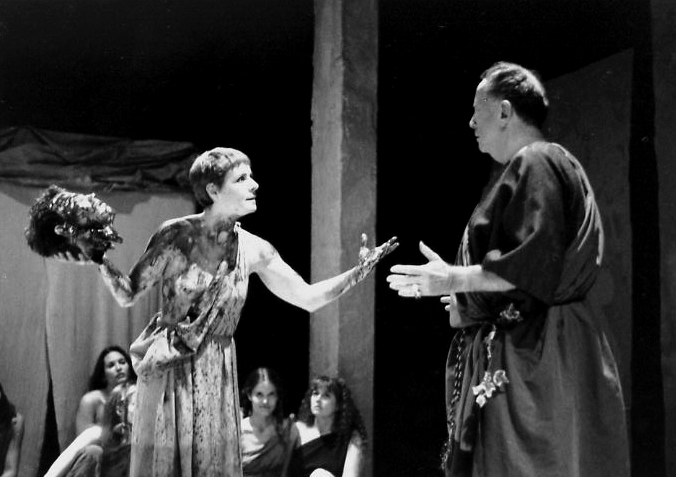

Faces, those identifying characteristics, are the first things to go. Contrast this with Euripides’ far more humanistic Bacchae, in which Agave’s mother returns from her Dionysian revels with her son’s head, so that she can recognize him as her victim.

In Book II, Lucan goes back decades to tell of the death of Roman warlord Marius, after he had been murdered by supporters of his long-time enemy Sulla:

“Why did it please them

to mutilate Marius’ face as if it were worthless,

and destroy their advantage? For, to please Sulla

with their bloody misdeed, he’d have to have been

still recognizable.Civil War II.201-205

In a spot of irony, Lucan puts these words in the mouth of an unnamed Roman elder, recounting the tale from someone without an identity in the first place. This annihilation of identity against reason seems to be the natural endpoint for all forces. The human identity is a ruse put upon the action of natural bodily forces.

When he speaks of the death of Carus, it’s the blood that becomes the active force, not metaphorically but in place of any human agency:

From the upper deck fights Catus,

who boldly holds a Greek ship’s painted sternpost

when from both sides two spears pierce his chest and back—

deep inside his body the steel meets and clashes,

and the blood is unsure from which wound to flow

until a mighty surge of blood casts both spears out

and divvies up his soul between the deadly wounds.

Civil War III.611-617

That’s Fox’s Penguin translation, which I’ve been using primarily because it is a bit easier reading than Braund’s. She renders the last three lines:

and the blood stood stilll, unsure from which wound to flow,

until at one moment a flood of gore drove out both spears,

split his life, and dispersed death into the wounds.Et stetit incertus, flueret quo volnere, sanguis,

Donee utrasque simul largus cruor expulit hastas

Divisitque animam sparsitque in volnera letum.

Life is split up and his blood escapes his body, replaced by death.

Immediately after, we hear the tale of two unnamed twins, treated as a united pair:

There were twin brothers, a fertile mother’s glory,

born from the same womb for different fates.

Cruel death parted the men, and their poor parents

no longer mistook them but recognized the one

who had survived—a cause of endless tears.

Ever after he caused them pain and moaning

because he looked like his lost brother.

Even their parents mistook them for one another; only one’s death allowed them to be distinguished. Of the lost brother we hear:

That one had dared

to grab hold of a Roman ship from his Greek deck

when the oars of both were tangled like a comb,

but from above a heavy blow cut off his hand,

yet it clung where he grabbed, on account of his grip,

and stiffened there, holding on, the sinews tense in death.

His virtue surged in misfortune. His wrath grows heroic

now that he is maimed. He renews the fight with his left hand

and leans down to the water to snatch up his right hand—

this hand, too, with the whole arm is sheared off.

Now without sword or shield he does not hide

down in the ship, but stands there and bares his breast

to protect his brother’s armor, he endures the points

of many weapons that would have killed many others,

and though long since earning death, he still holds on.

Then, with his life escaping through numerous wounds,

he gathers what’s left in his limbs and strains with all his blood

to jump on the enemy ship—but the sap in his nerves is gone

and only his body’s dead weight is left to do damage.

There’s definite comedy here of the Monty Python Black Knight variety: the soldier that persists in fighting even after losing his arms. The mutilation makes the twin more valorous, more heroic, and less human. The reversal in the bolded lines has his naked body becoming his brother’s armor. (Braund points this out as a reversal; thanks to Gabriella Gruder-Poni for helping me out with the ambiguous Latin arma tegens here.) He becomes a shield, and then a dead weight cannonball, his nerves having given out before that. What remains of his blood is enough to get his body onto the enemy ship.

Blood as a life force is not an unusual trope, but Lucan constructs an exceptionally material universe for it to inhabit, in which psychology and emotion (those things held in the face) are ephemeral manifestations of a more permanent organic scheme in which life is a very temporary and very particular arrangement, subject to dispersal. Moreover, what we call “life” and “human” is pure convention.

We (or parts of us) just as easily become weapons or armor. Or even love objects. In a very brief moment of harmony in Book IV, soldiers on either side of the war recognize each other and celebrate together (before one side then goes and brutally murders the other later that night):

One calls a friend by name, one greets a relative, 190

others recall youth shared in childhood pursuits.

Any who did not know a foe, was not a Roman.

Weapons run with tears, kisses break into sobs,

and though not stained with blood one soldier fears

what he could have done….Come now, Concord, unite all in an eternal bond

of embrace, this diverse universe’s salve

unto wholeness, along with holy World Love….Oh Fate, you are a sinister power! That brief respite

only making the slaughter worse. There was peace.Civil War IV.190-210

Even here, individual identity is dispersed. It’s the weapons that cry, individual gestures separated from the individuals who made them. The universe briefly alights on an image of love, complete with seemingly fatuous hymn from Lucan, only to reorder itself back into the far more usual brutality a few lines later. The omnipresent anonymity, the consequence of the dissolution of identity, is frightening.