The Civil War is an epic steeped in rhetoric, or more precisely, birthed from the font of rhetoric. Rhetoric and rhetorical training was crucially important to writers of Lucan’s era in particular, but the entire classical world had an art and science of rhetoric that often gets short-changed because Plato, who opposed and distrusted the art of rhetorical persuasion (all the while using it), has won the battle of posterity in recent centuries.

But while speeches play a significant persuasive role in much Greek and Roman literature, Lucan’s epic takes a vastly more ironic stance toward the role of rhetoric. So often in Lucan, words are merely a form of force, their meaning purely relative to the situation in which they are employed, bereft of further significance. The first analogue that comes to mind is the proto-Machiavelli Chinese Legalist Han Fei (280-233 BC), who offers the following advice:

The important thing in persuasion is to learn how to play up the aspects that the person you are talking to is proud of, and play down the aspects he is ashamed of. Thus, if the person has some urgent personal desire, you should show him that it is his public duty to carry it out and urge him not to delay. If he has some mean objective in mind and yet cannot restrain himself, you should do your best to point out to him whatever admirable aspects it may have and to minimize the reprehensible ones…. This is the way to gain the confidence and intimacy of the person you are addressing and to make sure that you are able to say all you have to say without incurring his suspicion.

Han Fei (tr. Burton Watson), quoted in George Kennedy, Comparative Rhetoric

It’s hard to say if Lucan is quite so cynical about the use of language, because Lucan is so fevered that his commitment to any principle, even that of ironic relativism of meaning, is difficult to assess. Nonetheless, there are many speeches in Civil War where it is clear that the import of their words is tailored to the situation and not meant to hold any greater meaning beyond it. Yet for those situations, when rhetoric serves as a spur to action, rhetoric is more powerful than any other instrument.

There is a very clever scene in Book III when Caesar tries to inspire his men to further bloody battle, but the weary and nervous troops are still hesitant to invade their homeland.

So [Caesar] spoke, but the doubtful crowd grumbled

hushed and unsure murmurs. However fierce their minds

and spirits swelling for slaughter, their fathers’

household gods, and piety, break them. But grim

love of steel and fear of their leader recall them.

Civil War III.382-7

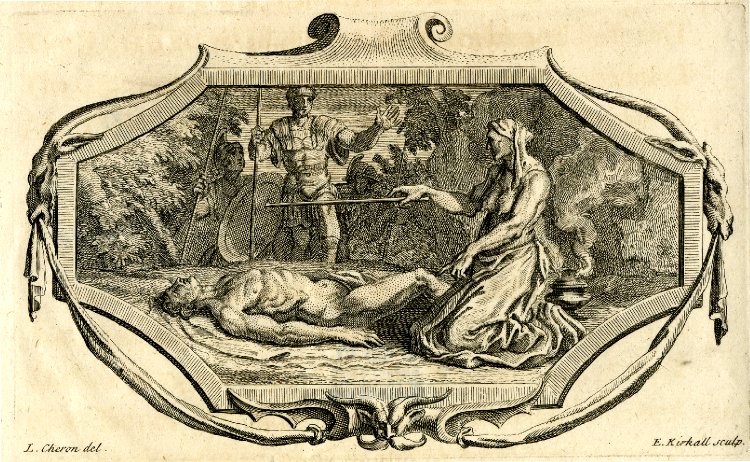

In what seems to be a parodic reversal of the Iliad’s infamous scene with Thersites, where a low-ranking soldier speaks out against the Trojan War and gets humiliated and beaten by the aristocratic officer corps, Lucan has a high-ranking officer, Laelius, speak up and say exactly what Caesar wants to hear.

“If I may, O greatest governor of the Roman name,

and if it is right to confess true words—that you

have held in check your strength with long endurance

is our complaint. Have you lost your trust in us?

As long as warm blood moves our breathing bodies

and strength of arm remains to spin these long spears,

will you suffer the toga’s disgrace and the Senate to reign?

And is it really so dreadful to win a civil war?….

“Whatever walls you wish to throw down, level flat,

these arms will drive the ram to strew their stones.

You just name the city and I will utterly raze it,

even if it is Rome.” All at once the cohorts

gave their assent and made known with high hands

their pledge to take part in any war he charged them.

This is Laelius’ only appearance in the entire poem. Taking Han Fei’s advice to the hilt, Laelius reverses Caesar’s speech, telling Caesar that it is not they who have lost trust in Caesar but Caesar who has lost trust in them: of course they are loyal to him and will follow him in anything! But this bit of brown-nosing is not aimed at Caesar but at the rank and file. The issue becomes one of pride: surely Caesar’s worries about his men’s loss of faith can’t be true, can they?

Caesar’s rhetoric later becomes an explicit means to drive the men out of their right minds, to keep them in the fighting spirit. When they rebel, he demeans them while putting himself above the gods and embracing the Great Man theory of history:

“You really think

your efforts for me have ever carried weight?

The gods don’t care, they’d never stoop so low,

the Fates don’t give a damn about your life or death.

Everything follows the whims of men of action.

Humankind lives for the few.”…

They trembled at his savage threatening voice,

a helpless mob afraid of a single man whom they,

so many strong young men, could have turned

back to private life—as if his orders

could wield against their will the very iron

of their swords. And Caesar himself was worried

that they might refuse their weapons for this crime.

But they submit to cruelty easier than he hoped:

not only a sword but throats came forward, too.

Nothing inures minds to crime like killing

and dying. So a grim pact was struck, restoring order;

the troops scattered, appeased by punishments.

Civil War V.356-391

He orders other soldiers to execute the deserters, and they do. The executions reinforce their support of Caesar—or else why would they have assented? Caesar once more grows closer to his army, and his crimes are identified with their crimes. Rhetoric binds them together and drives them into an irrational, almost dissociated state of mind, the sort the Greeks termed ἄτη (Atë).

A great deal of the rhetoric revolves around freedom and liberty, and while Lucan sometimes extols the cause of liberty, he and his characters often question the use of the term in the cause of war. When the tribune Metellus begins to take up arms to stop Caesar from raiding Rome’s treasury, a citizen named Cotta convinces him otherwise with some exceedingly twisty logic:

“The people’s liberty, when tyranny constrains it,

perishes through liberty. But you preserve her shadow

if you willingly do what you’re ordered. Being conquered,

we’ve submitted to so much unfairness. Our only excuse

for disgrace and baseborn fear is that we could not resist.

Just let him pilfer quickly the evil seeds of dreadful war.

Such losses affect peoples who still maintain their rights.

Poverty falls heaviest not on slaves but on their masters.”

Civil War III.153-160

The arguments are highly debatable, especially given the outcome of the war, but the speech works. Metellus doesn’t even respond.

One climax of rhetorical power comes at the end of Book IV, where a number of Caesar’s men are surrounded and attempt to escape by sea on rafts. One raft is surrounded by Pompey’s forces, and the commander of the doomed raft, Vulteius, urges his men to mass suicide with a lengthy, hyperbolic speech:

“I do not know what example you’re planning, Fortune,

by our great and memorable fates. But in all of history,

whatever annals record as monuments to loyalty

in service to the sword, of military duty,

our company would surpass them. For we know, Caesar,

falling on our swords for you is not enough.

But nothing greater remains, hard-pressed as we are,

than for us to offer great pledges of devotion.

Envious Fortune has cut off much of our glory,

since we are not captives with our sons and fathers….

“I have deserted life, my comrades, and wholly live

by my impulse for coming death! It is a frenzy!

Only those who are touched by the nearness of death

are permitted to realize what a blessing it is—

the gods hide this from survivors, to keep them alive.”

Civil War IV.521-548

Note that Vulteius invokes Fortune as “jealous,” a trait normally applied to the old Greek/Roman gods (the Greek word is φθόνος phthonos). This is a sign that Vulteius does not know what he is talking about, since Fortune is implacable and capricious, obeying no predictable laws. And the actual death reads as black comedy:

First the ship’s captain,

Vulteius, bares his neck and begs to meet fate:

“Is there any at all whose right hand is worthy

to spill my blood? Who will attest his faith,

seal his vow to die by stabbing me?”

He can say no more, for right then many a sword

drives his vitals through. Praising them all, he bestows

his grateful dying blow on the one who stabbed him first.

They fall on one and all, a single faction

committing every unspeakable act of war….

So the young men fall, sworn to share one fate,

and amid such manly deaths, to die takes little valor….

Now the half-dead drag their sprawling guts across

the deck and flood the sea with bloody gore;

ecstatic with the sight of the light they’ve spurned,

they behold their victors with proud faces

as death comes down.

Perhaps something has been lost or gained in translation, but this hardly reads as a dignified treatment of the mass suicide. It’s more of a burlesque, with the men in some kind of ritualistic trance from the violence.

Yet Lucan uses rhetoric as much as he depicts its power. The endless apostrophes and rhetorical questions in Civil War give it a far more demonstrative feel than the Aeneid, and according to Mark P.O. Morford in his short but very helpful The Poet Lucan: Studies in Rhetorical Epic, there are entire passages that follow classical rhetorical rules of organization.

Keeping that in mind, Lucan’s sincerity comes into question when, at the end of the suicide scene, Lucan appears to be praising Vulteius and his men:

But cowardly nations will still not understand

these men’s example: how a simple feat of bravery

frees you from slavery. Instead, kings use iron

to terrify, liberty is branded by savage armies,

to keep us ignorant that swords are for setting free!

Death, why not force cowards to stay in life,

and come to only those with valor?

This seems to argue that cowards should remain alive as punishment for cowardice, and a love of death is a better guarantor of freedom than anything else. If this is sincere, it has little to do with the particular cause. There is enough in Vulteius’ speech to mark him as a deluded warrior following an undeserving leader (Caesar), but perhaps Lucan is also emphasizing that death is preferable in any event to capture and enslavement?

If so, it’s a nihilistic message, since it implies that death is a boon regardless of the wrongness of cause or the comical grotesqueness of method. But there is enough elsewhere in the poem to make one wonder if this message is sincere even at all. So it’s on that note of uncertainty that I leave off on the first four books.