Richard Biernacki’s book, cursed with the unwieldy title Reinventing Evidence in Social Inquiry: Decoding Facts and Variables, is frequently incisive, sometimes inspirational, and sometimes frustrating. Biernacki vigorously attacks the use of quantitative methods in social science, particularly as applied to texts. He finds their usage to be slapdash, prejudiced, and dependent on lumping disparate phenomena under a single label, often in whatever way happens to serve the researcher’s pre-ordained goal.

I have to cheer when he cites Erving Goffman and Clifford Geertz as spiritual guardians:

“Whatever it is that generates sureness,” Goffman intimated darkly, “is precisely what will be employed by those who want to mislead us.” Goffman left it to us to discern how the riddle of cognitive framing applies to sociological practice and to one’s framing of one’s own results. Geertz expressed a similar kind of caution more cheerfully: “Keeping the reasoning wary, thus useful, thus true, is, as we say, the name of the game.” The only intellectual building material is self-vigilance, not the reified ingredients “theory” or “method.”

Damn straight.

Biernacki’s points are very well-taken, and his individual critiques are devastating. He has little trouble justifying his main charge:

If you reconstruct how sociologists mix quantitative and text-interpretive methods, combining what is intrinsically uncombinable, you discover leg-pulling of several kinds: from the quantitative perspective, massaging of the raw data to identify more clearly the meanings one “knows” are important or, again, standardized causal interpretations of unique semiotic processes; to zigzagging between quantitative and interpretive logic to generate whatever meanings the investigator supposes should be there.

Each study was narrated as a tale of discovery, yet each primary finding was guaranteed a priori.

Where I have a problem is his suggested retreat to a “humanist” mode of inquiry, which, while extremely attractive to people like myself, does not necessarily solve the underlying problem. I will explain this later.

The Indictment

Biernacki has a huge range of reading behind him and he quotes a number of people of whom I’m very fond: Robert Musil (who gets the last word in the book), Erving Goffman, Flaubert (Dictionary of Received Ideas), Michael Frede, Ronald Giere, Barrington Moore, William Empson, Jeanne Fahnestock, Wilfrid Sellars, Kenneth Burke, Samuel Beckett, Mary Douglas, Novalis, Cosma Shalizi, Eleanor Rosch, Valerio Valeri, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Andrea Wilson Nightingale, Erwin Panofsky, and Erich Auerbach. (Bibliography available online here.) Now that I’ve written it out, let me go further: that’s an amazing list.

I’m not particularly keen on most of his targets either, so we overlap sufficiently that I’m baffled at his elevation of Giorgio Agamben, whose attack on quantitative sampling is needlessly overwrought and jargony. Biernacki’s prose, unfortunately, tends toward the same. His thinking is in fact quite clear and rigorous, but the overlay of sociological jargon gets quite dense at times and needlessly prolongs things. (I’ll offer paraphrases of less transparent passages below.)

This applies to the general terms as well. Biernacki defines the social science term “coding” as such:

Coding, a word that may introduce an aura of scientism, is just the sorting of texts, or of subunits such as paragraphs, according to a classificatory framework.

What the social sciences deem “coding”–the application of a common typological label to variable individual cases–would better be simply called “labeling” or perhaps “classification.” I prefer “labeling” because it is the simplest and the most informal. As Biernacki demonstrates, the research being carried out is anything but formal, and so building a fence around a particular textual method is misleading. While it may make it easier to delegitimize that particular method, it also limits the scope of his critique. It also makes it seem as though this process is distinct from the labeling we do every day of objects and actions, when I think any difference is one of degree and not of kind.

To make the broadness of the critique clear, my article The Stupidity of Computers describes very similar methods, except applied to people and objects as well as texts. I used “ontology” instead of “classificatory framework” and “labeling” instead of “coding,” but they’re fundamentally analogous. Or as I put it:

Who decided on these categories? Humans. And who assigned individual blogs to each category? Again humans. So the humans decided on the categories and assigned the data to the individual categories—then told the computers to confirm their judgments. Naturally the computers obliged.

If anything, things seem worse in academic sociology, which is the field Biernacki treats. I am not familiar with the subfields Biernacki investigates and after his dip into those waters, I don’t have much desire to become familiar with them. Here is Biernacki’s brief:

Ironically, researchers who visualize a pattern in the “facts” often assert it symbolizes an incorrigible theory for which no data were required anyway.

They would turn meaningful texts into unit facts for the sake of converting these units back into meanings. What are the epistemological functions of the curious process of decontextualizing for the sake of recontextualizing? Cumulating the coding outputs purchases generality only if we know the codes rest on justifiable equivalencies of meaning, which is to return us to the original verbal settings that may vary incommensurably.

Paraphrase: sociologists are engaging in circular reading of texts. The squeeze a corpus into their frameworks and then reapply the frameworks onto specific examples to produce pre-ordained results.

My thesis is that coding procedures in contemporary sociology, the beachhead for coding texts that is spreading into history and literature, follow the rites by which religious believers relabel portions of the universe in a sacred arena for deep play. As in fundamentalist religious regimes, rejecting the enchantment of coding “facts” is nothing less than blasphemy.

Paraphrase: precisely because of their lack of any more fundamental support, the frameworks are sufficiently shaky that they are protected by hierarchical social structures that emerge around vulnerable belief systems, shutting down critics and elevating allies/toadies/grad students. For less opaque examples, see the conservative movement’s classification of “liberal” bias, or much of the talk that constitutes privilege-checking. Both utilize postulated frameworks supported by mantric rhetoric and repetition to obscure the lack of conceptual support. (And yes, I know the former is far more harmful, but today’s Right doesn’t have a monopoly on all forms of stupidity, since a large number of people have not realized that this chart is a joke.)

The ultimate point of this book is to stand social “science” on its head as less rigorous than humanist approaches. The social “scientists” of culture, those claiming a kind of epistemological advantage via their coding apparatuses, are instead intuitive cultists without openly sharable procedure. Opposite much orthodoxy, humanist craft workers who footnote and who convey symptomatically the wondrous in their readings are truer to the ideals of so-called hard science conventionally understood. As I endeavor to show, the nonsystematizing humanists still appreciate the obstacles to induction, the gift of an acute trial, the insurance of shared documentation, and the transformative power of anomalies. My brief is not the cliché that humanist interpretation aims at insight different in kind. More subversively, I insist such interpretation better fulfills the consecrated standards to which social “scientists” ostensibly subscribe.

Paraphrase: the use of quantitative metrics in social science is usually decorative frosting utilized in order to make preconceived notions seem more objective. In actuality they’re rigged games. A thoughtful, passionate, genuinely humanist approach is more scientific than vacuous tables.

It is more transparent, therefore more faithful to inquiry, to assume radical difference in a population than to rush toward aggregating modern “facts” out of corpuses whose members are artificially assumed to have homologous structures.

He’s talking about texts here, but this would apply to any grouping of anything. How to put this into practice is a much thornier question.

The Evidence

Biernacki then presents three case studies of prominent papers in recent sociology. He has done the legwork of looking through the original sources to see how “objective” the classification process was. The results are disastrous. All three are not just littered with slanted interpretations, selective omissions, and poor fits, but outright errors and holes in logic. The demolition is extremely thorough, and the time required to do the research might have boosted Biernacki’s ire further. Here are representative examples from the three cases.

Bearman and Stovel, Becoming a Nazi: A Model for Narrative Networks (2000)

All the network data were extracted from a single Nazi story, but it was not an actual autobiography from Abel’s collection. Help from Peter Bearman together with detective hunting established that the researchers coded instead from “The Story of a Middle-Class Youth,” a condensation published in an appendix to Abel’s book in 1938. Although the intact story was at hand for Bearman and Stovel, and although they had secured English translations of complete stories from the Abel collection, they coded instead from an adaptation that indicated with ellipses where connecting segments had been deleted.

Bearman and Stovel adopt the same vocabulary to describe their own scientific outlook as they apply to a Nazi. They feature “abstraction” for converging on the essential: “Comparison within and across narratives necessitates abstraction . . . This is accomplished by grouping elements into equivalency classes” [83; see also 20]. When the researchers present the Nazi cognitive style, “abstraction” is again the key feature, but now using it to “order experience” is a character defect [85]. It is not we as network reductionists who have a rigid response in analyzing qualitatively incomparable situations, it is the Nazis with a “master identity” who do. [NB: They also complain about another researcher’s “abstraction”: “Real lives are lost in the process, and real process is lost in the movement away from narrative by this abstraction.”]

Wendy Griswold, The Fabrication of Meaning: Literary Interpretation in the Unites States, Great Britain, and the West Indies (1987)

This presentation, which appeared in 1987 in sociology’s most exacting journal, was greeted far and wide as offering confirmable and generalizable results. It remains probably the most broadly circulated classic whose findings rest on systematic coding of text contents.

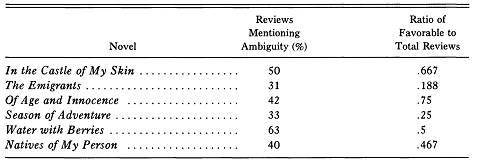

Griswold combined the reviews from each of her three regions—the United States, Great Britain, and the West Indies—to see if she could explain why some of George Lamming’s novels resonated more powerfully than others in her sample of reviews of his six novels in all. She guessed that “ambiguity” would not only engross readers in disambiguating the novels, but doing so would stimulate appreciative reviews. This just-so account presumes we can know what ambiguity is according to its function rather than by its verbal expression in a review. How exactly does creative engagement by the critics appear when articulated on the page of a book review? What is ambiguity on site? The blurring of appealing scientific hypothesis-testing with exegesis of highly compacted reviews produced a baffling gap: Griswold did not offer an example from her evidence to concretize this entity called “ambiguity,” yet social scientists propagated news about the abstraction in every direction.

When I took reviews in hand, it astonished me to find that at the individual level ambiguity is “specifically mentioned” (to my mind) primarily when the reviewer expresses frustration and disappointment. This dislike of ambiguity more often pushed a review over to a mixed or negative appraisal of a novel, reverse from Griswold’s report of correlations at the aggregate level…. Consider how baffling it is to identify “ambiguity” and “positive appraisal” on the ground.

If a resonant review, like a seminal novel, is multidimensional, and if the reviewer therefore does not try to locate the book on a metric of approval, the overall categories “positive,” and “mixed/negative” are not there in the text ready for translation. The summary is only a fabrication of the social “scientist.”

More subtly, by introducing the binary of colonialism as present or absent, the ritual cordons off the reality that it was daunting for British critics to avoid incorporating the relations of a concept as permeating as colonialism. Griswold never illustrates what counts as mention of colonialism or of any other theme.

John Evans, Playing God?: Human Genetic Engineering and the Rationalization of Public Bioethical Debate (2002)

To launch the sampling and coding ritual, we have to take up a schizophrenic consciousness between the quantitative-scientific and the humanistic-interpretive perspectives. We cannot acknowledge in one frame what we do in the other. Evans wrote that “the two foremost proponents of the form of argumentation in the bioethics profession as I have defined it,” Beauchamp and Childress, are not among authors charted as statistically influential. Indubitable knowledge from the humanist frame does not impinge on the “scientific” procedure for equating influence with citations.

Evans in the 2002 book Playing God produced importantly different diagrams out of the same data inputs as in the 1998 dissertation “Playing God.” How did this change transpire? For the 1992–1995 interval of debate, Evans raised the threshold for inclusion as an influential author in the cluster diagram from nine citations in the dissertation to ten in the book. This chart trimming changed the storyline significantly. For instance, the sociologist Troy Duster, whose work seems to run contrary to Evans’s thesis for the final period, 1992–1995, is among several other authors who dropped out of the diagram.

For a self-fulfilling prophecy Playing God filters out the epistles most pertinently aimed at the public. “If an item did not contain four or more citations, it was not included in the sample, because the primary technology of a citation study is measures of association between citations. I examined 765 randomly selected items from the universe. Of these, 345 fit the parameters for inclusion” [G 208].

“In my research,” Evans wrote, “the question was which top-cited authors were most similar to each other based on the texts that cited them” [G 209]. Similar how? Decades ago the analytic philosopher Nelson Goodman convincingly showed “similarity” lacks sense beyond particular and incommensurable practices of contrast and comparison. Whatever might we be talking about when we demonstrate what relative “influence” means by frequency citations and when we have no operative concept of influence outside this arbitrary measurement? As with ritual process, the models of citation counts merely bring to life a visual experience of a symbol’s use and substitute for the symbol’s conceptual definition.

Evans quotes Jonathan Glover as follows: “What he [Glover] envisions is a ‘genetic supermarket,’ which would meet ‘the individual specifications (within certain moral limits) of prospective parents’” [G 161]. Here again, findings appear to emerge by mischance. The words Evans attributed to Glover occur in a passage of Robert Nozick’s libertarian Anarchy, State, and Utopia, which Glover happened to quote before advancing toward a different position.

The kicker comes with a particularly noxious passage from Evans’ book, revealing the deep-seated self-justifying elitism at work in Evans’ a priori theorizing. Biernacki writes:

If my framing of Playing God as a ritual affirmation were plausible, we would predict that the policy recommendations with which the book concludes, while impracticably “utopian” [G 198], would impart an essential verity. That happens when Evans dismisses the need for real-world brakes on how elites would match particular means to an array of ends, once those ends were chosen by the public:

“If an ends commission decided that its ends to forward in genetic research were beneficence, nonmaleficence, and maintenance of the current specificity of genetic change as possible in the reproductive act, I have no doubt that bioethicists could determine which, if any, forms of HGE [human genetic engineering] advanced these ends. [G 203]”

As you might suspect given the abstractness of “ends in themselves,” it seems unlikely their implementation is a neutral technical job entrustable to specialist intellectuals. The experts in deciding how to pursue a mandated goal would, by concretizing it, subject it to reinterpretation. Would not the means that elites chose to institutionalize populist HGE policy have ramifying implications for practice, and thus values, in other spheres of life, short-circuiting public deliberation? Dealing with these practical issues in ritual is beside the point of affirming the transhistorical message that deliberation over ends should be protected from instrumental degradation.

The quote Biernacki cites here is incredibly damning, evoking images of a bioethical Comintern insisting that its ends are right and proper. Evans is the sort of powerless person you do not want in power.1

More generally, all three come off as tendentious, obfuscatory, and disingenuous, using numbers as a smokescreen for their unjustified suppositions. Biernacki is dead-on in stating that with more classical humanist criticism, you get to see upfront what sort of conceptual abstractions are taking place, subjective and case-based as they may be. Here, they hide behind the guise of objective abstractions plugged into a computational framework. (Shades of Ann Coulter’s Lexis-Nexis searches.)

The Dangers

I don’t doubt that these three works are representative. And Biernacki’s most fascinating point is that this misuse of science plays directly into theories of cultural determinism that have become very common across the humanities and social sciences:

The same problem of mixing scientific controls with texts occurs in demonstrating the theory of cultural power. That proposed theory starts firmly within the interpretive perspective, because it makes categories of understanding the “variable” that interacts with the novel to produce an engrossing experience. As Kenneth Burke emphasized, in an ideology-saturated society, readers deal with a plethora of contradictory schemas from which they choose how to interpret a text. Alternatively, much important literature, such as Beckett’s plays in the 1950s, from inside its own lines blatantly models unprecedented schemas from which a reader may learn to decipher the work as a whole—“the absurd.” To probe the fabrication of meaning, the reading process might be analyzed more fruitfully as a rhetorical operation rather than as a social one. Kenneth Burke intimated that inquiry into the schemas for reading might include syllogistic progression (step-by-step appreciation of a kind of argument pressing forward via the narrative), qualitative progression (the appreciation of feelings post-hoc from narrative action), antecedent categorical forms (such as “the sonnet”), or technical schemas (such as chiasmus and reversal). In any event, by underspecifying the cultural workings of the literary experience, we arrive at “society” as the default explanation of differences in the received meanings of the novels. The more you attend to the critics’ professional know-how and to the generative schemas with which they read, the weaker the rationale for leaping to a generally shared “percipience” to explain coding outputs. Sociologists since the nineteenth century have invested so much energy in solidifying “society” as a “cause,” they can invoke it without asking whether more tangible but less spirit-like forces may be operating.

Paraphrase: by reducing texts to a handful of ostensibly constituent effects and declaring them to constitute the text, researchers rob the texts of any power they might really have, using them as interchangeable totems for empty confirmation of unsubstantiated theories of cultural domination. Everything feeds back into a giant phantom of “culture” (or “capitalism” or “modernity” or “secularism” or take-your-pick) that ensures the identical outcome. Hence Biernacki’s point:

Ironically, researchers who visualize a pattern in the “facts” often assert it symbolizes an incorrigible theory for which no data were required anyway.

This is not only true, but even if they do not assert such, this is what’s going on anyway. There has to be some underlying theory conditioning the coding/labeling in the first place.

This complements Hans Blumenberg’s observations about the nature of generalized maladies. While Blumenberg emphasized the vagueness and generality of such overarching theories of discontent, Biernacki completes the thought by demonstrating that when the incorrigible theory is reapplied to specific cases, the specific cases become interchangeable.

In considering the prevalent openness to theories of ‘capitalism,’ one cannot fail to notice not only that there always seems to be a need for a causal formula of maximum generality to account for people’s discontent with the state of the world but that there also seems to be a constant need on the part of the ‘bourgeois’ theorist to participate in the historical guilt of not having been one of the victims. Whether people’s readiness to entertain assertions of objective guilt derives from an existential guiltiness of Dasein vis-a-vis its possibilities, as Heidegger suggested in Being and Time, or from the “societal delusion system” of Adorno’s Negative Dialectics, in any case it is the high degree of indefiniteness of the complexes that are described in these ways that equips them to accept a variety of specific forms. Discontent is given retrospective self-evidence. This is not what gives rise to or stabilizes a theorem like that of secularization, but it certainly does serve to explain its success.

Hans Blumenberg, The Legitimacy of the Modern Age

Biernacki’s point is that these theories not only accept a wide variety of specific forms, but that they also homogenize these forms. Cultural theory commodifies its subject matter.

Yet at this point the particular issue of quantification has fallen by the wayside in favor of the problem of incorrigible theories. For quantification per se, Biernacki’s evidence is less than ideal, because all three case studies contain such elementary errors in reportage and logic that they would be poor even if the quantitative aspects of the papers were removed. That is, I have no doubt that were Griswold or Evans to write a qualitative assessment of the texts they treated, they would not produce very good work either.

Biernacki is right to say that the scientific frosting obscures the poor quality of their work and exacerbates reductionistic tendencies toward cultural determinism, but the question of “coding” gets into problems that come up even in the absence of quantitative metrics, because coding is labeling, and labeling is what we do all the time.

The Solutions?

Though Biernacki limits the scope of his critique to labeling applied to texts, the arguments go through for ontologies applied to any phenomena. I think Biernacki gets into a muddle in trying to specify texts as specifically exempt from classification, contrasting words like “novel” with words like “dog”:

The intensional definition of “dog” is historically closed, whereas newly discovered literary works and financial instruments stretch and revise the anterior category of “novel” or of “a hedge-fund practice.” A previously unconsidered novel that stretches the distinctions between biography and fiction, for example, can remake the denotation of the label “novel.”

Intensions are dangerous things, and I think you could find that even seemingly clear concepts like “dog” can prove slippery in themselves. You would find more agreement among people, certainly, but who’s to say it’s enough? Labels are inherently unstable things. I think the very point of Beirnacki’s book makes it impossible for him to draw such a clear-cut line. Biernacki sometimes seems to assume that a stable “code” label is being assigned to unstable and ambiguous “data,” but there’s no reason to suppose the label is in general that much more stable than in the specific text.This is to enter philosophy of language issues that would derail this post entirely, so I will just leave matters at that unless someone wants to debate the point.

Consequently, the ultimate effect of Biernacki’s critique is to make the remaining space for quantitative science very small indeed. In this he is similar to Rudolf Carnap, whose requirements for science were so rigorous and unattainable that many philosophers of science (Popper among them) complained that he would put scientists out of a job. Certainly Griswold, Evans, and Bearman/Stovel come off much closer to Carnap’s idea of bad poetry (e.g., Heidegger) than science.

Contrariwise, I don’t see why the inclusion of quantitative measures in and of itself is a bad thing as long as the labeling is done in a sufficiently responsible way. Are interpretive reading and quantitative analysis “intrinsically uncombinable,” as Biernacki says? I admit that “sufficiently responsible” is a very high bar to clear. But while I agree that so-called “raw data,” is a misnomer, there is a difference between medium-rare and well-done. I would like to see Biernacki apply his methods to far more intelligent usages of corpus linguistics, such as those performed by Martin Mueller, Eleanor Dickey, Ian Lancashire, or Brian Vickers. All work at a far lower lexical level than Biernacki’s subjects, and all are better scholars. (And none is a sociologist. Biernacki does take a few swipes at Franco Moretti for following Griswold’s bad tendencies, but mostly leaves literature alone.)

But I want to push in the opposite direction as well against Biernacki’s elevation of what he loosely terms humanist interpretation (much as I love it). It is interesting that Biernacki makes a claim of rigor for his humanistic methodology. This is very tricky. When I read Auerbach and Spitzer and Fahnestock, I certainly get the impression of intense intellectual rigor, but rigor applied both to the careful reading of texts and to the holistic grasp of the whole. That is, because of the great difficulties in labeling, rigor must be accomplished by having both

- a heuristic, intuitive feel for the whole of one’s field and beyond, stemming from vast reading and reflection, and

- a complementary sense of where one’s knowledge is incomplete, where variations might occur, and what should be left open and tentative.

The blunt use of statistics can cover up the need for either of these time-consuming and tenure-threatening processes. Punch a corpus into a computer and analyze it and your work “seems” complete without your brain needing to process all the ambiguities and elisions. Clearly that is unacceptable. But ruling out quantitative measures is not necessarily more rigorous. Biernacki thinks very highly of Weber, and I do as well, to a point. But Weber’s theory of secularization and disenchantment has ultimately been overadopted by less imaginative minds than his. I think and hope that Weber intended his theses to be provisional, to be reassessed and revised (just as scientific theories should be) with the passage of time and research, not mindlessly parroted by crypto-conservative postmodernists looking to smuggle religion back into intellectual discourse under the guise of “reenchantment.”

To put it another way: is the generalized, reductive application of Freud’s theories any better than the generalized, reductive application of the DSM-IV?

This is not a complaint against Weber as much as it is frustration with general intellectual incompetence. What I mean to stress here is that I’m not so sure that this intellectual incompetence is so different in kind from the sort of intellectual incompetence Biernacki exposes in his subjects. Both stem from sloppiness, laziness, and a sheer lack of creativity. So while Biernacki rightly praises Panofsky:

The historian Robert Marichal followed Panofsky’s thesis to explain why the style of breaks in Gothic letters on parchment appeared simultaneously with the same breaks in stone, intersecting ribs in Gothic vaults. Both shifts expressed an analysis of whole lines to cut them down and regroup them into clearer, hierarchically ordered parts of parts. Compare this depth of analysis to a quantitative argument about net trends in abstract codes. Such blurred social “science” is less stringent about the patterning required for confirmation and too indefinite to isolate productive anomalies. Again the humanist focus on precise designs draws it closer to the rigor of the “hard” sciences.

I still think he overstates his case somewhat, because the “codes” at work here are just as subject to dispute. They are, however, more explicit, and this is a good thing, as Biernacki says. The issue, however, is that such great humanist works as he identifies are by their very nature exceptions, works of prodigious and unique minds that cannot be replicated en masse. The weaker philological work of years past is, alas, very nearly as formulaic as some of the scholarship Biernacki condemns (though far less sloppy).

As a prescription for better work, the humanist traditions provide little help in the mass production of research other than to set the bar so high for work that most people should immediately drop out of the field. (Not that this would be a bad thing, necessarily.) But it makes his prescriptions very difficult to imagine practically, unless academia is to return to being a elite, cordoned-off field as it was prior to the postwar higher education boom. (Though that may well happen.)

I am being speculative here, and none of this dampens the force of Biernacki’s critique. It just steers his critique more in the direction of “Don’t use numbers to cover up your incompetence” rather than “Don’t ever use quantitative measures on texts.”2

Science, ideally speaking, provides a workable means for adjudication of disputes, and even occasionally consensus, that is less dependent on the most powerful person around dictating what’s right. To a point, Biernacki employed science, in tandem with humanistic close reading, in his book to undermine the very bad “science” of the works he examined. That, I think, is the best model going forward that we have.

- Perhaps not so powerless. Only after writing this entry did I discover that John Evans was involved in a UCSD scandal to attempt to prevent Biernacki from investigating Evans’ work. In 2009, UCSD’s Social Sciences Dean Jeffrey Elman threatened to censure and dismiss Biernacki on the grounds that Biernacki’s research “may damage the reputation of a colleague and therefore may be considered harassment.” Full story here. IHE article here. It is appalling that Jeffrey Elman has retained his position as Dean after sending such a letter. Needless to say, my support for Biernacki’s pursuit of this research is total. ↩

- The sociological establishment is having an easier time attacking the second thesis, however, judging by Andrew Perrin’s nasty review. Perrin adopts a ridiculous “They aren’t trying to be scientific” defense, which leaves you wondering what all those charts are doing in the papers, as well as wondering what the point of such sociology is. Perrin also didn’t disclose that he is friends with John Evans until pressed in the comments. ↩