When it comes to scholarship and criticism, I prefer Jacob Burckhardt’s amateur/specialist dichotomy to Isaiah Berlin’s fox and hedgehog:

The word ‘amateur’ owes its evil reputation to the arts. An artist must be a master or nothing, and must dedicate his life to his art, for the arts, of their very nature, demand perfection.

In scholarship, on the other hand, a man can only be a master in one particular field, namely as a specialist, and in some field he should be a specialist. But if he is not to forfeit his capacity for taking a general view, or even his respect for general views, he should be an amateur at as many points as possible, privately at any rate, for the increase of his own knowledge and the enrichment of his possible standpoints. Otherwise he will remain ignorant in any field lying outside his own specialty, and perhaps, as a man, a barbarian.

But the amateur, because he loves things, may, in the course of his life, finds points at which to dig deep.

Jacob Burckhardt, Reflections on History (1868)

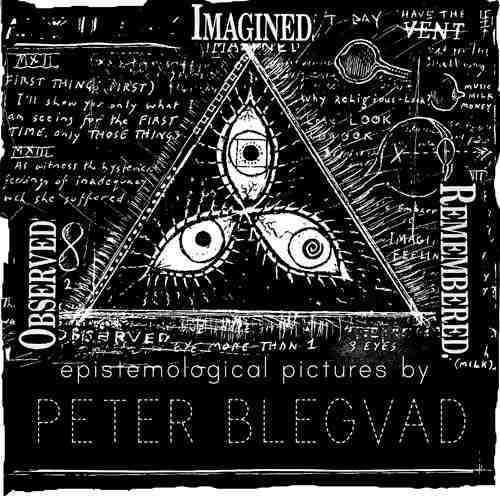

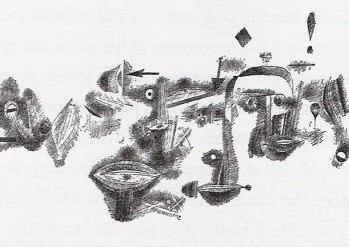

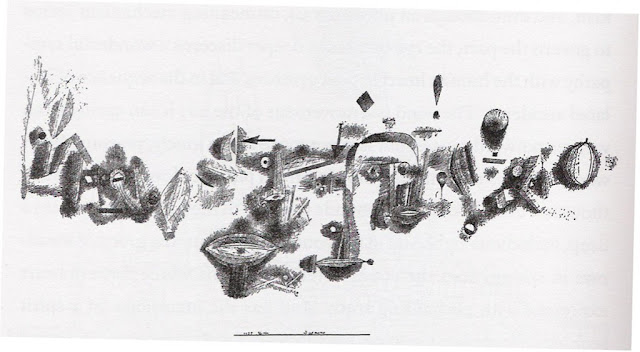

He sets a high bar! It’s possible this quote inspired writer/artist/cartoonist/musician Peter Blegvad to call his website Amateur Enterprises.

PB: I don’t deny it. I’ve always had an immature horror of being defined, so that’s part of it too. Would I have made more progress or been more successful if I’d devoted myself to just one form of expression? Who knows? I’m not thus constituted. I’m a dilettante, “polymorphously perverse,” a perpetual amateur. But let us not forget that amateur derives from amor. The miracle is that at fifty-eight years old, I’m still being paid to do things I love doing and no one’s ordering me to change it to fit some target audience.

(Blegvad has cited Guy Davenport, who embodies the “amateur” as well as anyone.)

Wayward, Odyssean scholarship opens up pathways that less imaginative specialists will miss. But an academic like Keith Thomas will still see connections simply from a voracious intake of knowledge. The danger is not in professionalism, but in complacency and a blinkered point of view. Burckhardt is opposed to the specialist who, like sociobiologist and race-scientist C.D. Darlington, thinks he’s found the root of all phenomena in a single discipline and method:

A specialised scientist stares down his microscope for 40 years and does very good work. Towards the end of his career he asks himself about the wider meaning of it all. He racks back the focus knob on the microscope, tilts the instrument back, and looks about him through its eyepieces. He stares hard for a time, a marvellous gleam comes into his eyes, and he exclaims, “I understand all!”

“The enrichment of possible standpoints” is the crux of it. There’s no real substitute for knowing many things about many things.