When Richard Nixon died, some op-ed or other bemoaned that his death was used as an occasion to forget, not to forgive. I thought the same when William F. Buckley died, and even Christopher Hitchens (a few people like Katha Pollitt excepted).

When Richard Nixon died, some op-ed or other bemoaned that his death was used as an occasion to forget, not to forgive. I thought the same when William F. Buckley died, and even Christopher Hitchens (a few people like Katha Pollitt excepted).

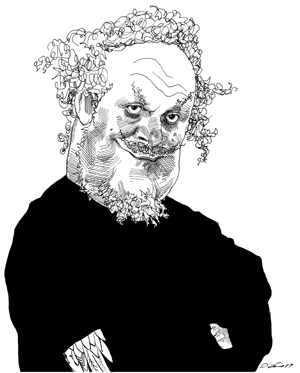

With that in mind, here are some Robert Bork quotes not to forget. Many are taken from his book Slouching Towards Gomorrah. This man has had a greater impact on the world than almost any other modern writer I’ve written about.

Be sure to read the last quote on the Port Huron Statement even if you skip those in the middle. It’s the punchline.

Robert Bork on gun control:

As the carnage continues, the public is offered such false panaceas as “midnight basketball” and gun control. Midnight basketball is so obviously a frivolous notion that it need not be discussed. Gun control is no less frivolous.

As law professor Daniel Polsby demonstrates, “the conventional wisdom about guns and violence is mistaken. Guns don’t increase national rates of crime and violence – the continued proliferation of gun control laws almost certainly does.” Gun control shifts the equation in favor of the criminal.

Robert Bork on feminism, choice, and sexuality:

Feminist gatherings within traditional denominations celebrate and pray to pagan goddesses. Witchcraft is undergoing an enormous revival in feminist circles as the antagonist of Christian faith…The feminists within the [Catholic] church engage in neo-pagan ritual magic and the worship of pagan goddesses.

The fact that men, who did not cry ten years ago, now do so indicates that something has gone high and soft in the culture.

Kate O’Beirne, Washington editor of National Review, said, “In the end, our girls are going to have to fight their girls.” True, but after that, some males in the academic world, in the military, and in Congress are going to have to summon up the courage to begin to repair the damage feminism has done.

Radical feminists concede that there are two sexes, but they usually claim there are five genders. Though the list varies somewhat, a common classification is men, women, lesbians, gays, and bisexuals.

But it is clear, in any event, that the vast majority of all abortions are for convenience. Abortion is seen as a way for women to escape the idea that biology is destiny, and from the tyranny of the family role.

As one might suspect from their hostility to men, marriage, and family, radical feminists are very much in favor of lesbianism. They want not only lawful lesbian marriages but “reproductive rights” for lesbians. That means the right to bear children through artificial insemination and the right to adopt one’s lesbian partner’s child. Since sperm is sold freely in the United States, much more freely than in other nations, there are lesbian couples raising children. It takes little imagination to know how the children will be indoctrinated.

Cornell’s training session for resident advisers featured an X-rated homosexual movie. Pictures were taken of the advisers’ reactions to detect homophobic squeamishness.

Robert Bork on women in the military:

The armed forces have been intimidated by feminists and their allies in Congress…In physical fitness tests, very few women could do even one pull-up, so the Air Force Academy gave credit for the amount of time they could hang on the bar. During Army basic training, women broke down in tears, particularly on the rifle range.

The Israelis, Soviets, and Germans, when in desperate need of front-line troops, placed women in combat, but later barred them. Male troops forgot their tactical objectives in order to protect the women from harm or capture, knowing what the enemy would do to female prisoners of war. In the Gulf War a female American pilot was captured, raped, and sodomized by Iraqi troops. She declared that this was just part of combat risk. But can anyone suppose that male pilots will not now divert their efforts to protecting female pilots whenever possible?

Robert Bork on multiculturalism:

Though many Hispanics are white, the law in its impartiality treats them as though they were not. Hispanics, who will outnumber blacks in the United States by the end of the century, often do not regard this country as their own.

Americans of Asian extraction had seemed to be immune to this rejectionist impulse. Yet, perhaps feeling ethnic grievance is necessary to one’s self respect, Asian-American university students are starting to act like an ethnic pressure group.

So far as I know, no multiethnic society has ever been peaceful except when constrained by force. Ethnicity is so powerful that it can overcome rationality. Canada, for example, one of the five richest countries in the world, is torn and may be destroyed by what, to the outsider, look like utterly senseless ethnic animosities. Since the United States has more ethnic groups than any other nation, it will be a miracle if we maintain a high degree of unity and peace.

Robert Bork on religion:

Culture’s affecting the churches more than churches are affecting the culture. But you can see how for example, the abortion rate is higher among Catholics than it is among Protestants or Jews. I picked that because the church’s opposition to abortion absolute opposition is well known, but apparently it is not affecting the behavior of the Catholic congregations. And I think similar examples could be drawn from Protestant churches and Jewish synagogues.

It is not helpful that the ideas of salvation and damnation, of sin and virtue, which once played major roles in Christian belief, are now almost never heard of in the mainline churches. The sermons and homilies are now almost exclusively about love, kindness, and eternal life. That may be regarded, particularly by the sentimental, as an improvement in humaneness, indeed in civility, but it also means an alteration in the teaching of Christianity that makes the religion less powerful as a moral force. The carrot alone has never been a wholly adequate incentive to desired behavior

Robert Bork on cultural decline, music, and censorship:

The very fact that we have gone from Elvis to Snoop Doggy Dogg is the heart of the case for censorship.

One evening at a hotel in New York I flipped around the television channels. Suddenly there on the public access channel was a voluptuous young woman, naked, her body oiled, writhing on the floor while fondling herself intimately…. I watched for some time–riveted by the sociological significance of it all.

alt.sex is on the Internet. That’s a category. They have a variety of things under alt.sex, which is alternative sex. Particularly horrifying was this alt.sex.stories. I don’t know how to work the Internet yet, but I did that research. I found it written up.

Irving Kristol was going through Romania back when it was a Communist dictatorship, and he learned that, of course, they banned rock ‘n’ roll on the grounds it was a subversive music. And it is, but not just of Communist dictatorships. It’s subversive of bourgeois culture, too.

Dixieland music had real themes to it, had often a very complex musical form. The music of today, a lot of the stuff we’re talking about rap seems to be nothing but noise and a beat without any complexity or without any I don’t understand why anybody listens to it. Well, rock ‘n’ roll still had some melody and I don’t think it could express a lot of emotions that the music before that could express. But it still had some melody and some distinction. And the melody gradually dropped out until we just have this rap.

A lot of people comfort themselves with the thought that this is confined to the black community, but that’s not true — some of the worst rappers are white, like Nine Inch Nails.

Radical individualism is the handmaiden of collective tyranny.

Robert Bork on science:

The fossil record is proving a major embarrassment to evolutionary theory. Michael Behe has shown that Darwinism cannot explain life as we know it. Scientists at the time of Darwin had no conception of the enormous complexity of bodies and their organs.

Upon fertilization, a single cell results containing forty-six chromosomes, which is all that humans have, including, of course the mother and the father. But the new organism’s forty-six chromosomes are in a different combination from those of either parent; the new organism is unique. It is not an organ of the mother’s body but a different individual. This cell produced specifically human proteins and enzymes from the beginning…It is impossible to say that the killing of the organism at any moment after it is originated is not the killing of a human being.

Physician Heal Thyself Dept:

The Port Huron Statement is a stupefyingly dull document and full of adolescent self confidence and arrogance about their ability to change the world and their superior wisdom about how to change the world and what it should look like.