Gore Vidal was before my time. Yet he was notorious as a name, and certainly I was taught that being on the opposite side of William F. Buckley and Norman Mailer was a good thing.

Gore Vidal was before my time. Yet he was notorious as a name, and certainly I was taught that being on the opposite side of William F. Buckley and Norman Mailer was a good thing.

But as a youth, the significance of Myra Breckinridge was lost on me when Woody Allen talked about it, and I was sheerly baffled at the SCTV sketch where Norman Mailer makes a commercial for Tide Detergent based on him squabbling with Vidal:

But so were my parents. That’s Martin Short as Vidal and Eugene Levy as Mailer–Joe Flaherty did an excellent William F. Buckley, who alas goes missing here.

In college, I read the voluminous essay collection United States. I admired Vidal’s social liberalism, particularly his blanket condemnation of the war on drugs, not a well-advertised view then. But the greatest impression was made by his 1965 thrashing of Henry Miller–specifically of Sexus, but really of the man, his personality, his very existence. It is a primo demolition job and his criticisms dovetailed with certain traits I continue to disdain.

Vidal was also hilarious, heavily assisted by choice quotes from Sexus itself:

Right off, it must be noted that only a total egotist could have written a book [Sexus] which has no subject other than Henry Miller in all his sweet monotony. Like shadows in a solipsist’s daydream, the other characters flit through the narrative, playing straight to the relentless old exhibitionist whose routine has not changed in nearly half a century. Pose one: Henry Miller, sexual athlete. Pose two: Henry Miller, literary genius and life force. Pose three: Henry Miller and the cosmos (they have an understanding).

The narrative is haphazard. Things usually get going when Miller meets a New Person at a party. New Person immediately realizes that this is no ordinary man. In fact, New Person’s whole life is often changed after exposure to the hot radiance of Henry Miller. For opening the door to Feeling, Miller is then praised by New Person in terms which might turn the head of God—but not the head of Henry Miller, who notes each compliment with the gravity of the recording angel. If New Person is a woman, then she is due for a double thrill. As a lover, Henry Miller is a national resource, on the order of Yosemite National Park. Later, exhausted by his unearthly potency, she realizes that for the first time she has met Man … one for whom post coitum is not triste but rhetorical. When lesser men sleep, Miller talks about the cosmos, the artist, the sterility of modern life. Or in his own words: “…our conversations were like passages out of The Magic Mountain, only more virulent, more exalted, more sustained, more provocative, more inflammable, more dangerous, more menacing, and much more, ever so much more, exhausting.”

Now there is nothing inherently wrong with this sort of bookmaking. The literature of self-confession has always had an enormous appeal, witness the not entirely dissimilar successes of Saints Augustine and Genet. But to make art of self-confession it is necessary to tell the truth. And unless Henry Miller is indeed God (not to be ruled out for lack of evidence to the contrary), he does not tell the truth. Everyone he meets either likes or admires him, while not once in the course of Sexus does he fail in bed. Hour after hour, orgasm after orgasm, the great man goes about his priapic task. Yet from Rousseau to Gide the true confessors have been aware that not only is life mostly failure, but that in one’s failure or pettiness or wrong-ness exists the living drama of the self. Henry Miller, by his own account, is never less than superb, in life, in art, in bed.

At least half of Sexus consists of tributes to the wonder of Henry Miller. At a glance men realize that he knows. Women realize that he is. Mara-Mona: “I’m falling in love with the strangest man on earth. You frighten me, you’re so gentle…I feel almost as if I were with a god.” After two more pages of this keen analysis, she tells him, “Your sexual virility is only the sign of a greater power, which you haven’t begun to use.” She never quite tells him what this power is, but it must be something pretty super because everyone else can also sense it humming away. As a painter friend (male) says, “I don’t know any writer in America who has greater gifts than you. I’ve always believed in you—and I will even if you prove to be a failure.” This is heady praise indeed, considering that the painter has yet to read anything Miller has written.

Miller is particularly irresistible to Jews: “You’re no Goy. You’re a black Jew. You’re one of those fascinating Gentiles that every Jew wants to shine up to.” Or during another first encounter with a Jew (Miller seems to do very well at first meetings, less well subsequently): “I see you are not an ordinary Gentile. You are one of those lost Gentiles—you are searching for something…With your kind we are never sure where we stand. You are like water—and we are rocks. You eat us away little by little—not with malice, but with kindness…”

Yet Henry never seems to do anything for anyone, other than to provide moments of sexual glory which we must take on faith. He does, however, talk a lot and the people he knows are addicted to his conversation. “Don’t stop talking now…please,” begs a woman whose life is being changed, as Henry in a manic mood tells her all sorts of liberating things like “Nothing would be bad or ugly or evil— if we really let ourselves go. But it’s hard to make people understand that.” To which the only answer is that of another straight man in the text who says, “You said it, Henry. Jesus, having you around is like getting a shot in the arm.” For a man who boasts of writing nothing but the truth, I find it more than odd that not once in the course of a long narrative does anyone say, “Henry, you’re full of shit.” It is possible, of course, that no one ever did, but I doubt it.

Interlarded with sexual bouts and testimonials are a series of prose poems in which the author works the cosmos for all it’s worth. The style changes noticeably during these arias. Usually Miller’s writing is old-fashioned American demotic, rather like the prose of one of those magazines Theodore Dreiser used to edit. But when Miller climbs onto the old cracker barrel, he gets very fancy indeed. Sentences swell and billow, engulfing syntax. Arcane words are put to use, often accurately: ectoplasmic, mandibular, anthropophagous, terrene, volupt, occipital, fatidical. Not since H. P. Lovecraft has there been such a lover of language.

Then, lurking pale and wan in this jungle of rich prose, are the Thoughts: “Joy is founded on something too profound to be understood and communicated: To be joyous is to be a madman in a world of sad ghosts.” Or: “Only the great, the truly distinctive individuals resemble one another. Brotherhood doesn’t start at the bottom, but at the top.” Or: “Sex and poverty go hand in hand.” The interesting thing about the Thoughts is that they can be turned inside out and the effect is precisely the same: “Sex and affluence go hand in hand,” and so on.

In nearly every scene of Sexus people beg Miller to give them The Answer, whisper The Secret, reveal The Cosmos; but though he does his best, when the rosy crucial moment comes he invariably veers off into platitude or invokes high mysteries that can be perceived only through Feeling, never through thought or words. In this respect he is very much in the American grain. From the beginning of the United States, writers of a certain kind, and not all bad, have been bursting with some terrible truth that they can never quite articulate. Most often it has to do with the virtue of feeling as opposed to the vice of thinking. Those who try to think out matters are arid, sterile, anti-life, while those who float about in a daffy daze enjoy copious orgasms and the happy knowledge that they are the salt of the earth.

This may well be true but Miller is hard put to prove it, if only because to make a case of any kind, cerebration is necessary, thereby betraying the essential position. On the one hand, he preaches the freedom of the bird, without attachments or the need to justify anything in words, while on the other hand, he feels obligated to write long books in order to explain the cosmos to us. The paradox is that if he really meant what he writes, he would not write at all. But then he is not the first messiah to be crucified upon a contradiction.

What I didn’t realize at the time was that the opposing force to such a narcissistic, hedonistic, self-important ass could possess some of those very qualities himself. But then, “he is not the first messiah to be crucified upon a contradiction.”

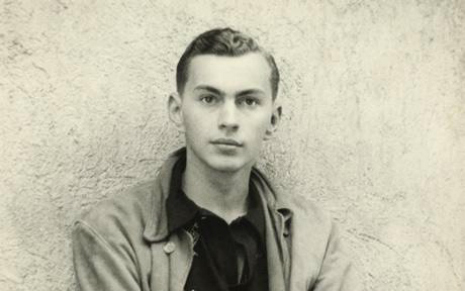

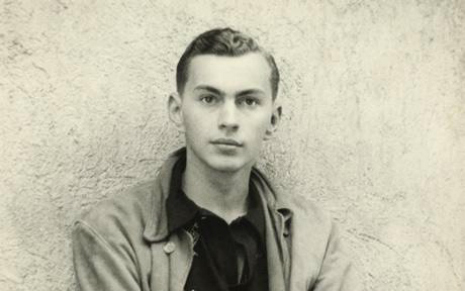

Anaïs Nin, who had both Vidal and Miller as lovers, wrote about him:

When Gore Vidal says he will be the President of the United States, I believe him. He walks in easily, not dream-fogged, not unreal, not bemused … His eyes are … clear, open, hazel. They are French eyes. His face is square … He came Sunday afternoon. Then this evening we sat at the Number One bar and talked. His father is a millionaire. His grandfather was Senator Gore. His mother left them when he was ten to marry someone else. “She is Latin looking, vivacious, handsome, her hair and eyes like yours,” he said, “beloved of many.”

Gore talks about his childhood: “When my mother left me I became objective…I live detached from my present life…at home our relationships are casual…my father married a young model…I like casual relationships…When you are involved you get hurt. I do not want to be involved ever…” Mutely … Gore’s sudden softness envelops me.

Gore is a lieutenant at Mitchell Field. He comes in on weekends, and Sunday he came to see me. We had a fine talk, lightly serious, gracefully sad. He read me from Richard II. “Why was he killed?” I asked. “Because he was weak. I am not weak,” said Gore.

Vidal would later demolish Stephan and Abigail Thernstrom’s 1997 America in Black and White: One Nation, Indivisible in The Nation with equal but far more righteous wit, pointing out that Henry Louis Gates had brilliantly solved the problem of how to blurb his colleagues’ book: “This book is essential reading for anyone wishing to understand the state of race relations.” Indeed.

Vidal was a man of his time and a man against his time. Whatever his faults, and they were evidently legion, his resistance to received idiocy is to be admired.

As is his appearance on Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman.

3 August 2012 at 14:24

Let me disclose the gifts reserved for age

To set a crown upon your lifetime’s effort.

First, the cold fricton of expiring sense

Without enchantment, offering no promise

But bitter tastelessness of shadow fruit

As body and sould begin to fall asunder.

Second, the conscious impotence of rage

At human folly, and the laceration

Of laughter at what ceases to amuse.

And last, the rending pain of re-enactment

Of all that you have done, and been; the shame

Of things ill done and done to others’ harm

Which once you took for exercise of virtue.

Then fools’ approval stings, and honour stains.

From wrong to wrong the exasperated spirit

Proceeds, unless restored by that refining fire

Where you must move in measure, like a dancer.”

Little Gidding

T.S. Eliot

3 August 2012 at 15:07

It is the pain, it is the pain endures.

Your chemic beauty burned my muscles through.

Poise of my hands reminded me of yours.

What later purge from this deep toxin cures?

What kindness now could the old salve renew?

It is the pain, it is the pain endures.

The infection slept (custom or changes inures)

And when pain’s secondary phase was due

Poise of my hands reminded me of yours.

How safe I felt, whom memory assures,

Rich that your grace safely by heart I knew.

It is the pain, it is the pain endures.

My stare drank deep beauty that still allures.

My heart pumps yet the poison draught of you.

Poise of my hands reminded me of yours.

You are still kind whom the same shape immures.

Kind and beyond adieu. We miss our cue.

It is the pain, it is the pain endures.

Poise of my hands reminded me of yours.

Villanelle

William Empson

4 August 2012 at 13:33

Two or three weeks ago, a not-terribly-related search strayed me into Vidal’s review of Edmund Wilson’s 1930s journals, in which Vidal wrote “Today one is never quite certain why memoirists are so eager to tell us what they do in bed. Unless the autobiographer has a case to be argued, I suspect that future readers will skip those sexual details that our writers have so generously shared with us in order to get to the gossip and the jokes.” (As he would later write “I suspect that future literacy chronicles will find it odd that the generation of Wilson… should have felt dutybound to tell us at length exactly what they did or tried to do in bed.”). He writes this in the midst of nine paragraphs concerning what Wilson did in bed and thought about what others did in bed, including a full paragraph mocking Wilson’s interest in feet, and a note on the disputed size of his pink prong.

Very much the NYRB equivalent of a tabloid’s finely detailed outrage over what those awful perverts are doing. And I then remembered why I stopped being much interested in Vidal after I left high school.

4 August 2012 at 14:11

Apart from being considerably slower on the pickup than yourself, I think my experience was similar. I think his political importance as an out queer man of his time stands, but that doesn’t increase the posterity value of such essays as the one you link to.

I can’t help but be reminded of Matthew Wilder on Renata Adler on Pauline Kael.

6 March 2013 at 14:53

I don’t really see Vidal hoisted on his own petard here; he was accusing Miller of narcissism based on a book he wrote and published, not private conversations related by someone else entirely.

21 February 2020 at 18:36

Guns kill people. We must gun down people to get their guns. I use

my guns to kill people with who want to kill gun-confiscation laws.

“Hey wide-awake Steve, I got fifty-eight relaxing hours of Bangkok

whore-house moaning to combat your chronic insomnia. Listen and

you’ll feel a lot better I promise,” I said, four minutes before Steve’s

sister arrived from a Bangkok whore-house that she & Steve owned

where-from they made sexy recordings to combat chronic insomnia

for insomniacs requiring fifty-eight relaxing hours of hoes moaning

in a Bangkok whore-house. “Thanks a lot,” Moaned Steve sleepily.

21 February 2020 at 18:38

I can’t be stopped. Surely you can, anyone can. But how? With a bullet like the bullets that stopped John Lennon. Were they hollow- points? No. If they’d been he wouldn’t’ve walked so far. True. 30 bucks to park to see Paul’s replacement’s iffy. Yes. Very much so.

21 February 2020 at 18:40

My Magical Easter in North El Paso ~ Juan shaved his mother for rectal surgery while Diego & Marta skinned 2 cats for lunch. “Come here,” Marta said in Spanish to her brother Paco,“and rub my lard ass with Taco Bell hot sauce like a Tijuana pimp!”

18 March 2021 at 22:06

A bit ironic that Vidal who had his own “Empire of the Self” (to borrow the title of his friend, Jay Parini’s, biography) would accuse Miller of solipsism. While Miller writes in the manner of a diarist, his prose is very often verging on poetry, and good poetry at that – something utterly lacking in Vidal. Vidal’s self referential use of his own life experiences can also become repetitive at times. It’s also worth noting that Vidal denied Nin’s claims about their relationship.

15 January 2023 at 13:42

Vidal’s comments on Miller are hugely entertaining, but don’t make the mistake of skipping Miller; he is a fantastic, rollicking, transcendant, beastly, beautiful writer.