The excellent piece on Novalis in this week’s TLS quoted a bit of his brilliant Monolog, and it’s short enough I figured I’d just post the whole thing here:

Speaking and writing is a crazy state of affairs really; true conversation is just a game with words. It is amazing, the absurd error people make of imagining they are speaking for the sake of things; no one knows the essential thing about language, that it is concerned only with itself. That is why it is such a marvellous and fruitful mystery – for if someone merely speaks for the sake of speaking, he utters the most splendid, original truths. But if he wants to talk about something definite, the whims of language make him say the most ridiculous false stuff. Hence the hatred that so many serious people have for language. They notice its waywardness, but they do not notice that the babbling they scorn is the infinitely serious side of language. If it were only possible to make people understand that it is the same with language as it is with mathematical formulae – they constitute a world in itself – their play is self-sufficient, they express nothing but their own marvellous nature, and this is the very reason why they are so expressive, why they are the mirror to the strange play of relationships among things. Only their freedom makes them members of nature, only in their free movements does the world-soul express itself and make of them a delicate measure and a ground-plan of things. And so it is with language – the man who has a fine feeling for its tempo, its fingering, its musical spirit, who can hear with his inward ear the fine effects of its inner nature and raises his voice or hand accordingly, he shall surely be a prophet; on the other hand the man who knows how to write truths like this, but lacks a feeling and an ear for language, will find language making a game of him, and will become a mockery to men, as Cassandra was to the Trojans. And though I believe that with these words I have delineated the nature and office of poetry as clearly as I can, all the same I know that no one can understand it, and what I have said is quite foolish because I wanted to say it, and that is no way for poetry to come about. But what if I were compelled to speak? What if this urge to speak were the mark of the inspiration of language, the working of language within me? And my will only wanted to do what I had to do? Could this in the end, without my knowing or believing, be poetry? Could it make a mystery comprehensible to language? If so, would I be a writer by vocation, for after all, a writer is only someone inspired by language?

Novalis, “Monologue” (1798), tr. Joyce Crick

This, together with Kleist’s “On the Gradual Production of Thoughts Whilst Speaking”, make the deconstructionists seem rather late to their own game.

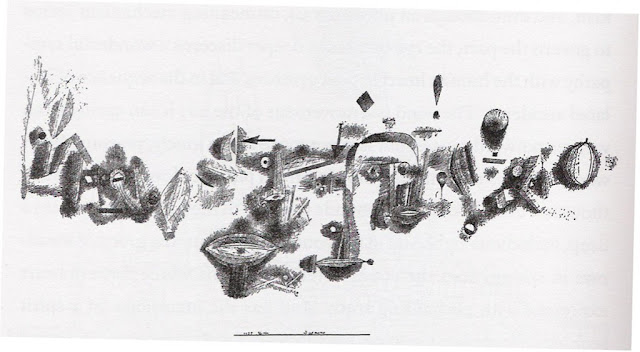

The artistic complement to Novalis here is Paul Klee, whose drawings inspired by The Novices of Sais capture some of what Novalis is saying. This one is called “Demony”: