Reductionistic Framework Alert!

I recently ran across an old essay by Lisp expert, venture capitalist, and general software guru Paul Graham. Graham is a very sharp person and his Lisp books are excellent, but he writes almost exclusively from a prism of an engineering-centric, Manicheistic worldview.

A good scientist, in other words, does not merely ignore conventional wisdom, but makes a special effort to break it. Scientists go looking for trouble. This should be the m.o. of any scholar, but scientists seem much more willing to look under rocks. [10]

Why? It could be that the scientists are simply smarter; most physicists could, if necessary, make it through a PhD program in French literature, but few professors of French literature could make it through a PhD program in physics. Or it could be because it’s clearer in the sciences whether theories are true or false, and this makes scientists bolder. (Or it could be that, because it’s clearer in the sciences whether theories are true or false, you have to be smart to get jobs as a scientist, rather than just a good politician.)

[10] I don’t mean to suggest that scientists’ opinions are inevitably right, just that their willingness to consider unconventional ideas gives them a head start. In other respects they are sometimes at a disadvantage. Like other scholars, many scientists have never directly earned a living– never, that is, been paid in return for services rendered. Most scholars live in an anomalous microworld in which money is something doled out by committees instead of a representation for work, and it seems natural to them that national economies should be run along the same lines. As a result, many otherwise intelligent people were socialists in the middle of the twentieth century.

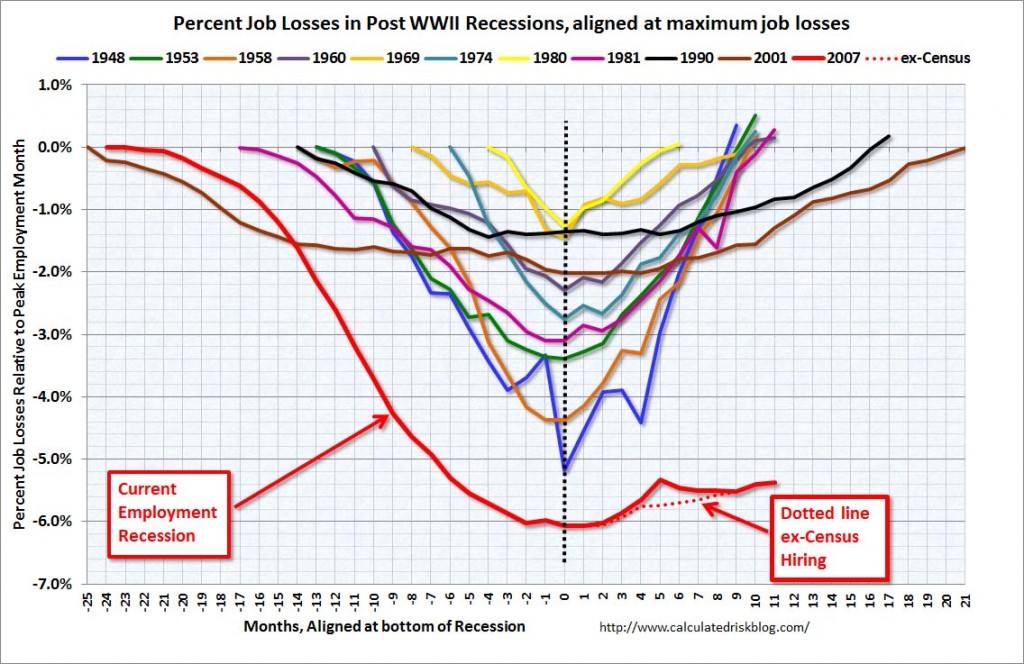

Some would call him a representative of “scientism,” which is the pejorative term for scientific positivism. Because I’m equally suspicious of reductionistic worldviews as well as quasi-spiritual appeals to the metaphysically irreducible, I’m not going to attack him for presenting the former and make it look like I’m appealing to the latter. I want to talk about him because I’ve been thinking about the future as the new year has come and I have been looking at depressing statistics about employment and poverty like these.

So I’ve been thinking about the future, and Graham seems to be a pure representative of one side of the two dominant power bases that appear to be duking it out for control of the US right now. The battle is between technocrats and ideologues, Whigs and Tories, libertarians and moralists. To avoid using any loaded terms, I’m just going to create two generic types of my own:

- Type L: libertarian, technocratic, meritocratic, pro-business, anti-government, laissez faire, pro-science, positivist, secular, elitist, progress-driven, Whiggish, optimistic.

“The best should have the power.”

- Type C: tradition-oriented, pro-status quo, nationalistic, protectionist, isolationist, xenophobic, social conservative, pro-business, pro-government (at least in regards to furthering other goals), pro-religion, cronyistic, chauvinistic.

“The powerful should have the power.”

These are not types of voters, but types of people of influence, people who in some way affect the policies that are being made. It’s my own heuristic. I thought about government policies of the last 30 years, from Reagan’s tax cuts to welfare reform to the health care bill, and then excluded all those people whose viewpoints didn’t seem to be reflected in them. This is what I was left with.

(Type C clearly holds assorted beliefs reflected in my less-funny-by-the-day Taxonomy of Conservatives, while Type L has beliefs called out in the taxonomy as not actually being conservative at all.)

If, like most people reading this, you don’t fit into either of these types, congratulations! Your opinion is probably not relevant to the dominant discourse in America. You’ll notice that what is not covered in these two types is any sort of socialist attitude advocating government intervention to encourage equality and welfare. This attitude appears to have vanished amongst the influential forces in American life, possibly owing to the decline of labor unions. When you realize that Paul Krugman is several degrees to the right of John Maynard Keynes, you see exactly how little purchase any sort of genuinely socialist attitude has in the country.

These two types are darker analogues of the “conservative” and “liberal” classes described by Leszek Kolakowski in his short essay “How to Be a Conservative-Liberal-Socialist.” Here are the ideas that fall under his “socialist” type:

A Socialist Believes:

1. That societies in which the pursuit of profit is the sole regulator of the productive system are threatened with as grievous–perhaps more grievous–catastrophes as are societies in which the profit motive has been entirely eliminated from the production-regulating forces. There are good reasons why freedom of economic activity should be limited for the sake of security, and why money should not automatically produce more money. But the limitation of freedom should be called precisely that, and should not be called a higher form of freedom.

2. That it is absurd and hypocritical to conclude that, simply because a perfect, conflictless society is impossible, every existing form of inequality is inevitable and all ways of profit-making justified. The kind of conservative anthropological pessimism which led to the astonishing belief that a progressive income tax was an inhuman abomination is just as suspect as the kind of historical optimism on which the Gulag Archipelago was based.

3. That the tendency to subject the economy to important social controls should be encouraged, even though the price to be paid is an increase in bureaucracy. Such controls, however, must be exercised within representative democracy. Thus it is essential to plan institutions that counteract the menace to freedom which is produced by the growth of these very controls.

I really don’t see much evidence of any of these attitudes in any of our ruling elites. Do you? I don’t think of myself as a socialist and I don’t endorse these views over those of Kolakowski’s other two classes, but the absence of fierce advocates for these views amongst the powerful is a really bad thing.

Democrats and Republicans as well as those calling themselves “conservative” and “liberals” each consist of various proportions of these two sides, but the mix is such a mess that I suspect there will be some serious realignment in the next ten or fifteen years. However, since the disconnect between what people say they believe and what policies they actually endorse only seems to be growing, I don’t dare predict what shape this realignment will take. It is very hard to predict how those depressing statistics will affect voting patterns. (Please see Larry Bartels’ “What’s the Matter with What’s the Matter with Kansas?“ to understand how wrong the conventional wisdom about voter bases can be. Stick with the raw statistics.)

So obviously Paul Graham is Type L and Glenn Beck is Type C. Why divide people in the middle by these two categories? Because this is where the social fissures seem to lie. The sharp engineering Type L’s like Graham want to be left alone so that their genius can rain prosperity down on society. Though they may believe in a social safety net, they are hostile to any sort of traditional authority structure not based in purportedly objective measures of merit. They don’t want to deal with people who haven’t earned their place beside them, and they definitely don’t want to work for them. The Type C’s have no such standard. They like people who are like themselves, and would much rather work with someone who shares their hobbies than with someone smarter than them. Type L will advocate for equality of opportunity and scholarships for smart kids from disadvantaged backgrounds. Type C most certainly do not want the best and the brightest of the unwashed masses rising up. They’re still unwashed, after all.

Graham is representative of many science and engineering types, the sorts that the US so desperately cultivated during the Cold War to keep pace with Soviet technology. Now they are cultivated by tech companies. Their strong libertarian streak comes from their (frequently mistaken) belief that talent and skill will deservedly win out and help improve the world, and so the more talented are entitled to more wealth and the fruit of their labors. They are not necessarily Ayn Rand sorts, but they are generally enamored of the view that competition encourages progress and efficiency. (I agree, to a point.)

It is a major mistake to think that the CEOs and bankers of today are Type L. While many of them lack the overt social conservatism and xenophobic stances of many Type C’s, they have no love for what Joseph Schumpeter called the “creative destruction” of capitalism. They have endorsed free trade and laissez faire policies because they have been good for their own interests, but they will beg for government handouts in a second and see no problem with colluding with the government to crush their competition and enemies. Lemon socialism, crony capitalism, socialism for the rich and capitalism for the poor; whatever it’s called, Type C loves it. Type L will sometimes, when push comes to shove, concede defeat and accede to a rebalancing of the playing field in the hopes of a better tomorrow. Type C wants the playing field tilted forever in their favor.

This is, more or less, the major reason why Microsoft was sued by the government while banks, energy companies, and so many others were left untouched. Microsoft didn’t think it needed to pal around with the old boy network. They were wrong. Tech companies have learned their lesson and now employ lobbyists as aggressively as those other companies, but their tendency toward Type L put them behind the Type C executives of most corporations when it came to politicking. You can get some idea of whether a company tends toward Type C or Type L by seeing to what extent minorities and women have infiltrated their executive ranks: Type C will keep them out without even realizing they’re doing it. Another good post facto signal for identifying Type L: they sometimes admit they were wrong. Type C will go to the grave believing in their divine right to be at the top of the ladder. While JFK’s “best and the brightest” might have had some loose claim to the title, Enron’s “smartest guys in the room” were so flagrantly not that it dirties the term “intelligence” to claim it for them.

Put in such stark terms, it’s easy for me to pick a side, but it doesn’t make me any happier with the choices.

One of the major annoyances with Type L is how shallow the use of reason often runs, leading to thinks like Graham’s conclusions above. This is not even a problem of scientific positivism per se, but just cursory laziness in its application. Yes, at the top of the heap there are good, searching thinkers like Joseph Schumpeter and a number of other economists, but the majority of the Type L people in the ruling class get their rigorous intellectual precision from Thomas Friedman, Malcolm Gladwell, Steven Levitt, Kenneth Pollack, and other proof-by-anecdote writers. They often commit the fallacy of thinking that others have as rigorous standards as they do, when (a) not only are their own standards not rigorous enough, but (b) others have even sloppier standards.

Paul Graham almost certainly has more raw brainpower than I do, but the mental heuristics used to assess evidence and theories in the hard sciences are usually catastrophic when applied to the social sciences. His statement is doubly ironic because he admits that theories in the sciences are more easily assessable even as he is declaiming The Way People Are with the same certainty with which Newton laid down his physical laws.

Type L are prone to believing in simple social laws for the same reason why scientists have so often been duped by psychics: they aren’t used to being tricked. Psychologists and economists aren’t deliberately trying to trick people, but their theories are built on sand compared to those of math and science, and so what they call a “conclusion” or “evidence” is usually an insult to the history of science. This is why things like Social Darwinism, The Bell Curve, and assorted other “scientific” justifications for inequality persistently make their way into supposedly rational people’s conventional wisdom. (The price of rationality is eternal vigilance. And eternal skepticism.)

For a perfect example of this sort of slippage from quantitative to qualitative, check out the collected works of Richard Posner. True to Type L, he has recently changed his views while still maintaining faith in efficient rational markets. Admitting a failure in the current implementation of free market capitalism is within his intellectual horizon; admitting irrationality into his view of the world is not.

So those are the two sorts of rulers I see. They got along reasonably well for a while, but the continuing economic problems are going to make it harder for them to paper over their differences as frequently. Let’s hope they look out for us all. Happy new year to you all and thanks for reading.

PS: As for the people who aren’t part of the above two power structures and receive their beliefs and dictats in a bewildering variety of ideologies and forms only tenuously linked to the real motivations at work…well, I quote Yes, Prime Minister:

Hacker: Don’t tell me about the press. I know exactly who reads the papers:

- The Daily Mirror is read by people who think they run the country;

- The Guardian is read by people who think they ought to run the country;

- The Times is read by the people who actually do run the country;

- The Daily Mail is read by the wives of the people who run the country;

- The Financial Times is read by people who own the country;

- The Morning Star is read by people who think the country ought to be run by another country;

- And The Daily Telegraph is read by people who think it is.

Sir Humphrey: Prime Minister, what about the people who read The Sun?

Bernard: Sun readers don’t care who runs the country, as long as she’s got big tits.

2 January 2011 at 21:33

Great post.

As a socialist-humanist type who is a keen observer of his betters, I’m fascinated by a recent turn in Type L thought: namely, its propensity for debunking and demystifying. These are traits that were always latent in Type Ls, and they’re clearly highly valued by this type as the passage from Graham shows. But in the last two decades or so, they’ve become the defining features of the Type L. The obsession with debunking is in contrast to an interest in system-building which you see in earlier, Cold War-era Type Ls.

The New Atheists. Mythbusters. The Sokal hoax. xkcd. An obsession with Popper and “falsifiability.” These are the monuments of Type L culture in its current incarnation. Your average science blog, for example, isn’t all that interested in doing science. Its main purpose is to call bullshit on bad thinking or fashionable nonsense or whatever. Science gets trotted out not to explain the world but to debunk its pretensions.

The weird thing about this – and your paragraphs about Type L’s shallowness of reason get at this nicely – is that there’s a disconnect between this largely cultural project of demystification and the actual work that Type Ls are engaged in.

In theory, the Type L is supposed to be a superb debunker of bullshit thanks to all the time he spent in the lab gathering and analyzing data, activities that ought to hone the mind into a obdurate skepticism (this is precisely the story Graham wants to tell, of course). In practice, though, the Type L is way more willing to fall back on un-reflected-upon assumptions when critiquing creationists or climate change denialists.

The practice of debunking makes use of anecdotes and totems (“The English professor down the hall uses jargon, therefore literary criticism is bullshit”) while the actual science and data—in short, the stuff that is supposed to underwrite the culture of debunking in the first place—falls off.

4 January 2011 at 20:32

Paul Graham and Jim Hacker in one post? No wonder this is one of the last blogs I still read.

7 January 2011 at 10:04

As representative types for the purpose of discourse, fair enough – but the discourse specious from a wider viewpoint?

From outside the USA, occasionally looking in, type L still comes across as a creature of the right (to use another reductionist framework…) versus the far-right C – which does hint, perhaps, towards sterility… Liberal – liberty, reserving the right to remove same from those lower in the hierarchy, as must(?) happen in capitalist/market economies. That’s what pro-business appears to mean.

The analysis quoted of the socialist ‘type’, in particular, comes across as very straw man – and the product of an embittered emigre, imagining that was actually ‘socialism’ that went on to the east of the Iron Curtain. And we do sometimes hear not even especially rabid commentators accusing Barack Obama of being a goddamn socialist – which causes much hilarity round here, as I’m sure it does in some circles in his country.

PS Please forgive any more-radical-than-thou tone…

24 January 2011 at 07:41

Roger: This dynamic has played itself out in analytic philosophy in a somewhat clearer way, as the more essentialist types have tended to search for any system that would make traditional atomistic logic salvageable, regardless of assumptions or not. Rorty vs. Soames discussed this to some extent, though Quine vs. Kripke is the grand battle. Jerry Fodor, whose views are all over the place, I think has it more or less right here: http://www.lrb.co.uk/v26/n20/jerry-fodor/waters-water-everywhere

Athene: Depressing, perhaps, but not specious. A country ruled by Type C would be very, very different from one run by Type L. Economically, Type C could be considered more “left” than Type L, hence the phrase “lemon socialism.” Neoliberal (or ex-neoliberal) economists actually do think that the bank bailouts were unfortunate.

Kolakowski obviously has it in for communism, so his portrait of socialism is affected by that, but I don’t think he’s being too negative about it. Even his super-moderate socialist portrait is far from anything reflected in American politics today, which is why I quoted it.

22 February 2011 at 06:01

I wonder if you’ve noticed a tendency in some of your writings lately to split things up into two opposing forces. With the Tom Disch article there was the Eichmann and the Wallace. With the Krasznahorkai article there was the Leviathan and the Behemoth — and Order and Chaos. With this, Type Cs and Type Ls.

22 February 2011 at 07:07

My recent writings have split into two types: those that you refer to, and those that do not display this tendency. Blumenberg’s Dichotomies is probably most reflective of my sense of the matter.

(Seriously, the least provisional dichotomy, in the sense of the one that I take most seriously, is the order v. chaos, and that one really is drawn from the opening of Blumenberg’s Work on Myth. Three Versions of Conservatism split into sets of three rather naturally, but originally came in sets of four before I collapsed a few distinctions. Finnegans Wake had a big influence in causing me to think that sets of 1, 2, and 3 things were fundamental and that higher numbers were generally reducible without too much loss of information. Peirce is the single thinker I know of who obsessively maintained a fixation on triadic sets (is there any time he puts forward a dichotomy?), and boy do I think that should get more attention. It’s there in Hegel (though his obvious movements are dichotomous and oppositional, and the “thesis/anthithesis/synthesis” trinity is utterly specious) and obviously in some Christian thinkers, but Peirce makes them look rather half-hearted. Disch and K. really do have a dualistic mentality, unlike, say, Leskov. For this piece, well, I wanted to replace the humanities v. science opposition with something more substantive, without complicating matters unnecessarily.)