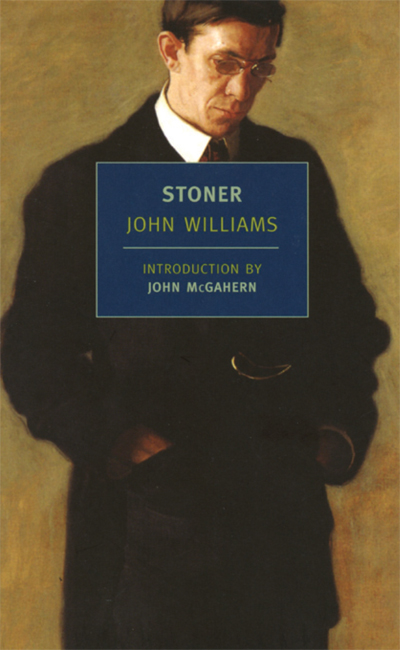

Whatever my reservations about the New York Review of Books, if it subsidizes reissues of things like this, I pardon its sins. Extra points for choosing such an apt cover painting to implicitly portray its hapless professor hero:

And here is Stoner speaking:

Stoner looked across the room, out of the window, trying to remember. “The three of us were together, and he said–something about the University being an asylum, a refuge from the world, for the dispossessed, the crippled. But he didn’t mean Walker. Dave would have thought of Walker as–as the world. And we can’t let him in. For if we do, we become like the world, just as unreal, just as…The only hope we have is to keep him out.”

Walker is an ignorant, smooth-talking, careerist academic, and there’s little separating his portrayal in this book (from 1965, but taking place mostly in the first half of the century) from these sorts of people today. Stoner is an impractical dreamer, a farmboy who goes to a local college and discovers he loves literature, and so does his graduate work at the same school and then gets a professorship there. He makes two mistakes: he marries the wrong woman, and he makes the wrong enemy in his department. These are big mistakes, and he pays big for them.

I cannot recall any other academic novel that treats its subject material with such unremitting gravity. The standard model of an academic novel is to either indulge in high melodrama (Mary McCarthy, Iris Murdoch) or to make light of the intellectual pretenses of its characters (Kinsley Amis’s overrated Lucky Jim, Malcolm Bradbury’s far funnier Stepping Westward). Williams’s approach seems to have been to adopt the social realist approach of George Gissingand Sinclair Lewis’s more sober moments and apply it to the incongruous and hermetic world of a university. Consequently, he treats the small events of Stoner’s life with a sense of real consequence, as though they were matters of life and death. And so they become.

After his mistakes, Stoner is a defeated man, and it takes him years to recover. But what saves the novel from being just an exercise in misery is that Stoner does get his triumph. He fights against the inertial decline of his life, and he wins. It is, objectively speaking, a small triumph, but on the terms that Williams has set, it validates his existence without qualification. The novel is a passage from ideals that cannot be fulfilled to a non-tragic view of life, and it’s summarized best in this passage:

In his extreme youth Stoner had thought of love as an absolute state of being to which, if one were lucky, one might find access; in his maturity he had decided it was the heaven of a false religion, toward which one ought to gaze with an amused disbelief, a gently familiar contempt, and an embarrassed nostalgia. Now in his middle age, he began to know that it was neither a stae of grace nor an illusion; he saw it as an act of becoming, a condition that was invented and modified moment by moment and day by day, by the will and the intelligence and the heart.

I don’t mean to downplay the brutally accurate portrayals of academic politics and fleeting trends, which feel absolutely au courant, but the novel would not stand out as it does if it did not treat its subject matter with the same respect and humility with which Stoner himself treats literature and teaching.

8 June 2008 at 10:43

Oh, good, another Malcolm Bradbury title to seek out (The History Man and Eating People is Wrong were great fun). As much as I liked Stoner (cf http://nnyhav.blogspot.com/2007/07/open-letter-to-myself.html ), Cynthia Ozick gives it a run for the money with The Cannibal Galaxy (though at a secondary level). But, contra Eudaemonist ( http://www.waggish.org/2003/04/american_writers_of_the_1950s.html ), I think Jarrell’s Pictures from an Institution is one book in this class managing to blend the satirical with the human (otherwise the satire would bite harder). Less arguably, Pnin is another.

8 June 2008 at 13:00

I actually thought History Man rather over the top and unlikable, though his parody of De Man et al. in Mensonge is pretty amusing.

Have to side with Eudaemonist on the Jarrell…it’s just too harsh and condescending for me. I would propose Wendell Kees’ Fall Quarter instead, though it’s not a great book.

As for Pnin, it’s an odd one because of its quasi-metafictional nature and the sheer Nabokovianness of it all. It’s a great book, but I find myself not thinking of it as an “academic novel” per se, so I think I unconsciously didn’t figure it into my assessment.

13 June 2008 at 19:02

OK, when I first saw the title of this post I thought you were going to reveal the little-known influence of marijuana on the composer who scored all those Spielberg movies. The book looks good and all, but . . .

15 December 2008 at 22:45

Or Pale Fire? Which actually reminds me a lot about Stoner, as though Lomax — Lomax on speed — were the narrator. (Shade = Stoner) Anyhow, for me one of the great minor things about Stoner is Gordon Finch, the dean — the completely unexpected friendship between them that’s the through-line of the book.

I think the writing is sometimes slightly slack (plainness requires a little bit more sustained care than Williams always gives it), but sometimes rises to amazing levels of controlled intensity (like the snow scene just before Katherine Driscoll re-enters). Anyhow, thanks for this, which got me to read it.

27 October 2009 at 02:17

Lucky Jim ‘overrated’? A wild understatement: terrible book.

4 April 2012 at 10:46

Thanks for this review. I finished Stoner last night and found it unexpectedly moving, particularly in the last scene with his daughter. I haven’t read a novel so lucid and straightforward in some time.

What I am still puzzled by though is why Stoner wanted to marry Edith—is it his naivety? Romantic illusion? Not sure, and the novel doesn’t seem to offer any clear answer.

2 April 2013 at 03:20

He wanted to marry Edith for the same reason anybody does in a society that still holds together on the firm post-war household values. Who can see how someone will turn out, especially if you’re a farm boy who has never interacted with a woman before? Perhaps those values account for why she never leaves him even though she despises him.

Funny thing about the book is that it follows Stoner around unremittingly, his every move, every sensation… and then twice it changes p.o.v and takes that of Edith: First time, in the bedroom when she discovers she does want sex with him after all, and the second time after her father’s suicide and she is alone in her childhood room, burning her old belongings. In these scenes there is no Stoner. This is non-systematic and odd.